Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In Annie Ernaux’s novelistic memoir “The Years,” she charts how a woman’s selfhood can slip away as she becomes enmeshed in new identities such as wife or mother. Through photographs, though, her old selves are preserved. Each time the shutter snaps, in that fragment of a second, she is crystallized in time: sempiternally sixteen, or twenty-seven, or forty-eight. Pictures have the power, Ernaux suggests, to “save something from the time where we will never be again.”

The photographer Rosalind Fox Solomon began quietly taking pictures of herself in middle age as her own identity started disappearing. Through a five-decade career, Fox Solomon has been renowned for capturing others in places both faraway—Peru, India, South Africa—and uncomfortably close to home. Now at ninety-four, she is releasing a book of self-portraits for the first time titled “A Woman I Once Knew,” which is published by Mack. It is somewhere between an autobiography and a photo book, with recollections and fragments of journal entries from childhood onward, positioned next to self-portraits spanning half a century.

Fox Solomon grew up in Highland Park, Illinois, to young parents who liked to drink Martinis and go to parties. Her writings about that period are filled with a longing for acceptance, both inside the household and outside. She dreamed of being a writer, but her mother, obsessed with classical femininity, encouraged her to abandon what she deemed idle reveries and instead focus on making herself desirable. “She believes in loveliness, graciousness, good breeding, and ladylike manners,” Fox Solomon writes. “Youth is my god,” her mother told her.

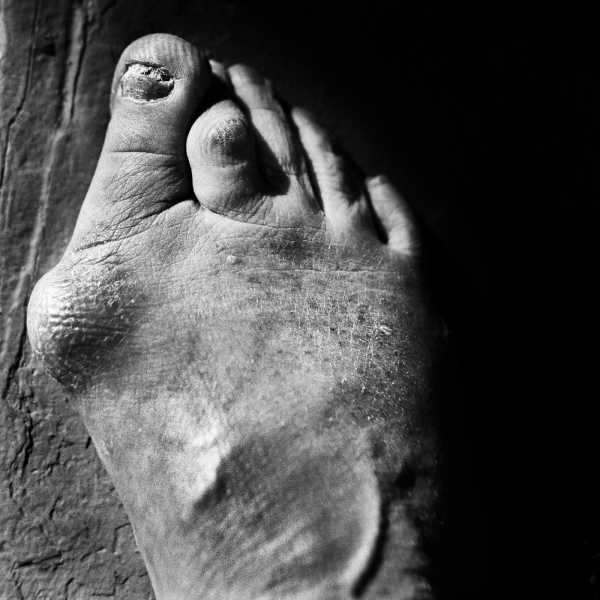

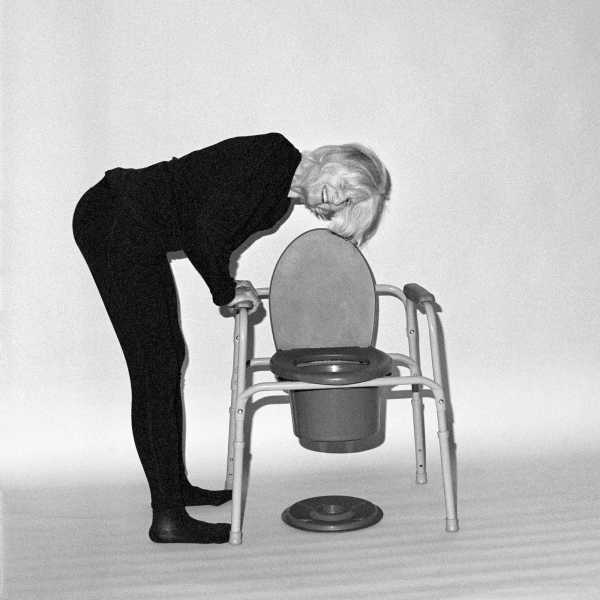

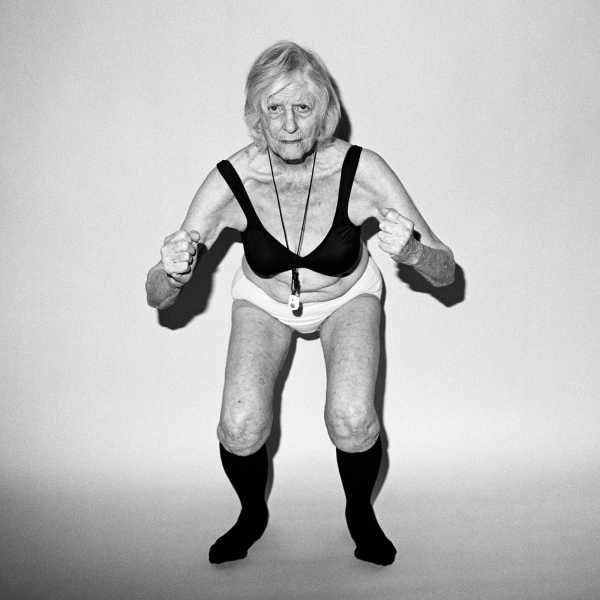

In defiance of this mantra, Fox Solomon lets the self-portraits in her book starkly convey the brutality of aging. Her pictures, many of them nude, feature open sores, shattered nails, and bones jutting out of feet almost to the point of pushing through the skin. These are not the images her mother would have approved of, nor do they follow in the traditional mold of the nude in art history. Where Ingres, Botticelli, and Titian sought to create an elongated and elegant form, Fox Solomon crouches, bends, and stares at the viewer. In one image, she hangs a picture frame around her torso, so that her breasts and genitals are encased in a gilded rectangle.

The text in “A Woman I Once Knew” proceeds more or less chronologically through Fox Solomon’s life, but the photographs, which are undated and uncaptioned, are time travellers. Wedged between a series of chiaroscuro nude portraits from middle age, Fox Solomon writes of her teen-age years and early adulthood. After graduating from college, she met Joel (Jay) Solomon, a politically connected Southerner who would go on to work with the Carter Administration, and, she writes, “we both felt waves of romantic bliss.” Love came with concession, though, as Jay did not want Fox Solomon to continue working when they relocated to his native Chattanooga, Tennessee. Six weeks after their honeymoon, she underwent surgery to remove uterine fibroids so that she could get pregnant; conducted by Jay’s cousin, the operation left her with a thin, serpentine scar up her abdomen that is visible in many of her photographs. “By the time I was twenty five,” she writes in the book, “he had sliced open my stomach twice again,” in two C-section operations during the births of the Solomons’ children, Joel and Linda.

Rosalind Fox was by then Rosalind Fox Solomon, and, like the woman in “The Years,” she was beginning her evanescence. Perhaps in an effort to stop herself from fading away completely, she began taking photographs—some of herself, some of other people. What began as an avocation turned into a serious occupation, as Fox Solomon turned to documenting the remnants of segregation visible in Chattanooga and across the South. She studied under the humanist photographer Lisette Model, who taught her, Fox Solomon writes, “to reach the raw, receptive state which could lead me to passionate connections.”

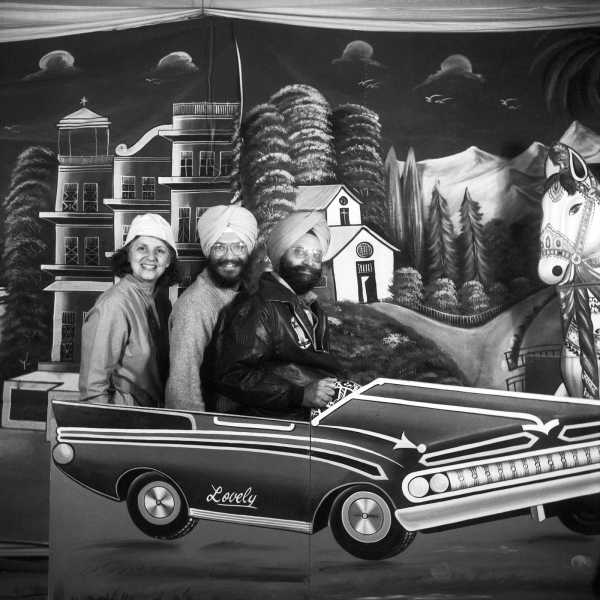

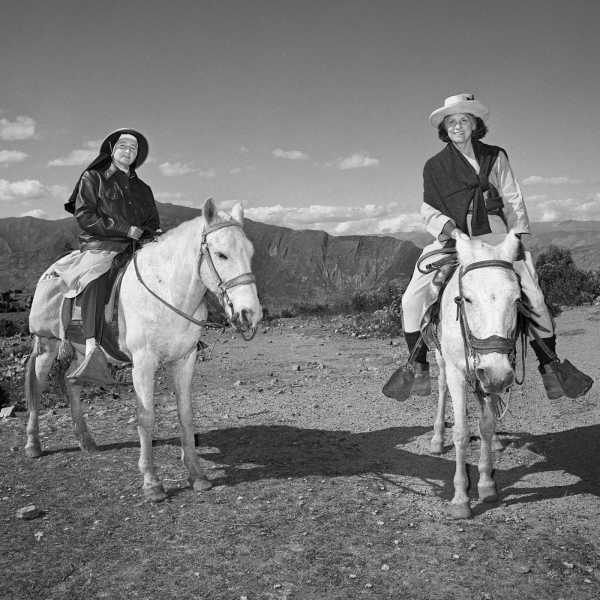

Fox Solomon is known for work in black-and-white, but there are flashes of color throughout the new book. The few times Fox Solomon is shown smiling, she is usually far away from home. She travelled alone in the nineteen-eighties, hiring local guides to help her navigate foreign territories and languages. Armed with a Hasselblad, she headed to a region in the Peruvian Andes where an earthquake had ripped across the land a decade prior. Near the village of Huari, her guide, a twenty-one-year-old Chilean man, came onto her, so she left at dawn and sought help from a church; a group of nuns took her in, and she gave them photographs as a token of thanks. Undeterred by the incident, Fox Solomon proceeded to Calcutta next. “For the first time, I have the pleasure of being in charge,” she writes, describing how she would “boss” around her drivers. “What a wonderful feeling it is to be managing men.”

Fox Solomon’s marriage eventually ended; in 1984, she found an artist loft in Manhattan, where she lives to this day, and decided to begin a new life there. Perhaps her most well-known body of work, “Portraits in the Time of AIDS,” occurred during those early years in New York; there is reference to that project in the text, but the only related image seems to be one of Fox Solomon standing in front of an M.T.A. subway car that’s whizzing by in its metallic glory. The subsequent photos return to an exploration of Fox Solomon’s own body and hands. Her self-portraits contain the same Caravaggesque tones as the rest of her portraiture, shunning veneer in favor of capturing something truthful beneath.

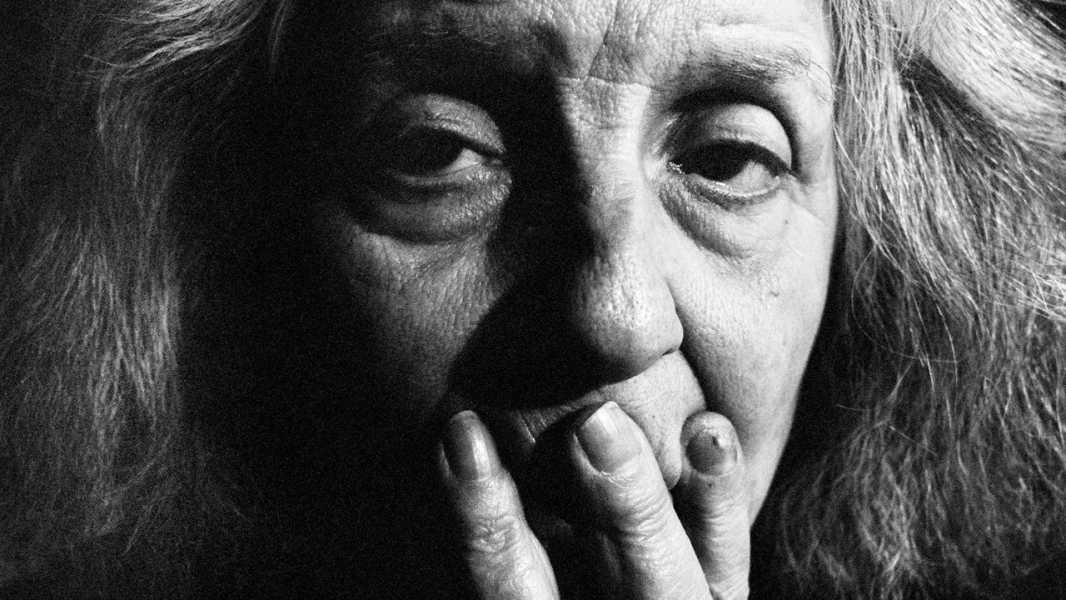

Nude portraits dominate the book, but not all of the images are confrontational. One unusually delicate image shows Fox Solomon veiled by a lace curtain, which renders the contours of her face and body soft. Still, “A Woman I Once Knew” does not fall into sentimentality as other works of memoir sometimes do. Joan Didion wrote that “we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be,” and Fox Solomon’s photographs appear to offer that: a look back at herself, not with mawkish nostalgia but with an elegy to her past selves. Fox Solomon has written that taking pictures was a way of “communicating to myself.” In a recent conversation via Zoom, I asked her about this idea. After thinking for a long moment, she said, “Maybe it was a connection with reality.” Throughout her life, her head swirled with thoughts of loneliness, and she ached for connection. In one journal entry, she writes, “Today is not fun Today is lonely / Today I am almost sixty-two The future is unclear I am muddled / Feeling outside of where I should be / And where is that?” One photograph shows the blur of Solomon’s eyes staring worriedly back at themselves as if inches away from a bathroom mirror. The closeness of the photo is distorting; the subject is both her and not her at all. Throughout the book, Fox Solomon tries different angles, different poses, as if to ask, Is this really me? As with Ernaux, photography is a way to firmly plant herself in space and time.

“A Woman I Once Knew” is, most likely, Fox Solomon’s swan song. The book betokens an acceptance of ever-encroaching mortality. “I feel a kind of detachment from my body, which is strange, but certainly something I didn’t feel earlier on,” she told me, adding, “at ninety-four, I don’t feel self-protective. Before long, I will be dust.” The closing image shows Fox Solomon with her eyes closed, contentedly resting her arms and her head along the top of a tombstone with her surname on it. Taken as a whole, the book is an appraisal of a life well-lived, not necessarily out of happiness but through tenacity and vigor.

Sourse: newyorker.com