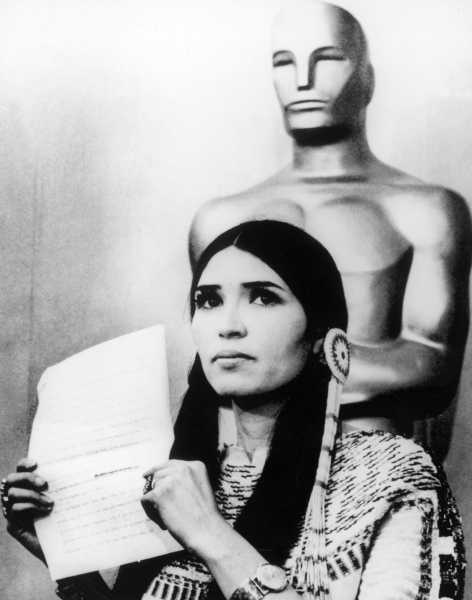

Sacheen Littlefeather holding Marlon Brando’s statement at the 1973 Oscars.Photograph from Hulton Archive / Getty

In the annals of astonishing Oscar moments—the streak, the slap, the envelope mix-up—none is more mind-bending than what happened on March 27, 1973, the night that Marlon Brando sent Sacheen Littlefeather to decline his Best Actor award for “The Godfather.” The twenty-six-year-old activist took the stage in a fringed buckskin dress and moccasins, held an abstaining palm to the statuette, and identified herself as Apache and as the president of the National Native American Affirmative Image Committee. The look in her eyes was firm but pleading, that of an uninvited guest who meant no harm. When she explained that Brando’s reasons for refusing the award were Hollywood’s mistreatment of Native Americans and the standoff in Wounded Knee, South Dakota, there were loud boos and scattered cheers. “Thank you on behalf of Marlon Brando,” she concluded, and walked off, leaving the audience at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion (and millions watching at home) in shock.

The backlash that began during her speech did not abate. Opening the Best Actress envelope moments later, Raquel Welch snarked, “I hope they haven’t got a cause.” (The winner was Liza Minnelli, and she didn’t.) The media tried and failed to locate Brando—his answering machine said, “This may sound silly, but I’m not here”—despite reports that he was on his way to Wounded Knee. The reaction to his protest, at least by the white press and white Hollywood, was overwhelmingly negative. “Actors can get on a soapbox,” Rock Hudson said. “But I think it’s often most eloquent to be silent.” (Hudson’s lifetime in the closet, and his death, from AIDS, twelve years later, makes this remark especially tragic.) The Academy’s president, Daniel Taradash, said, “Despite the fact that he said he made efforts not to be rude, Brando was rude.” One columnist balked at Brando’s “grandstand play, cloaked in hypocrisy,” calling the stunt “pretentious and demeaning to an industry that has made him a millionaire.”

Meanwhile, details emerged about the mysterious young woman whom Brando had sent in his place. Littlefeather was born Marie Cruz, the press reported, and had joined the Native American occupation of Alcatraz Island, in San Francisco, a few years earlier. She was also a Hollywood “bit player” who had done modelling work, appeared in a film as an “Italian prostitute,” and once been named Miss American Vampire, in a promotional contest for the horror flick “House of Dark Shadows.” The tabloids circulated a false rumor that she wasn’t really Native American—just another Hollywood pretender—and her proximity to the schlockier side of show business cast a cloud over her cause. “The industry she derided so soundly from her center stage Music Center pulpit,” another columnist clucked, “happens to be an industry she’s been trying to become a part of for years.” It was further revealed that, in 1972, Littlefeather had posed nude for Playboy, in a spread of horseback-riding “tribal beauties” that Hugh Hefner ultimately rejected. (“Well,” she told a newspaper at the time, “everybody says black is beautiful—we wanted to show that red is, too.”) Months after the Oscars brought her notoriety, Playboy ran the three-page spread of Littlefeather, who said that she was using the fee to attend a theatre festival in Europe. As the 1973 Academy Awards receded into history, the whole thing cemented into a pop-culture punch line: preening actor, fake Indian, kitschy Hollywood freak show.

But what if it wasn’t that at all? This summer, the Academy made the remarkable move of sending Littlefeather a formal letter of apology for the reception to her speech. “The abuse you endured because of this statement was unwarranted and unjustified,” it read. The apology reflected an Academy that has been hyper-attuned to inclusion in the wake of #OscarsSoWhite, and it brought renewed attention to the incident, which, from the distance of forty-nine years, is easy to see in a starkly different light. Hollywood’s representation of Native Americans was deeply racist for decades, and it is still meagre. Brando’s action, which precipitated decades of political-awards speeches (good and clumsy), was, we can now admit, pretty punk rock. Littlefeather, standing on a stage that had never welcomed anyone quite like her, was poised and courageous, and the mockery she endured was flagrantly sexist and racist. If it happened now, her appearance would surely set Twitter aflame, with some denouncing it as “wokism”—but many more hailing her as a role model. In 1973, Littlefeather was more talked about than heard. Almost half a century later, are we finally ready to listen?

Earlier this month, the Academy capped its reconciliation with Littlefeather with an event at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. The museum, which opened last year, has taken pains to address the demographic blind spots that have plagued the industry (and the Oscars), with displays on early Black filmmakers and stereotypes in classic animation. One exhibition, called “Backdrop: An Invisible Art,” shows the painted backdrop of Mount Rushmore from “North by Northwest”; one wall of text discusses Alfred Hitchcock’s craft, while another reminds us that the monument itself is a violation of the Lakota’s claim to the mountain, as promised in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The event, which was live-streamed, began with a land acknowledgement from a Tongva woman. Indigenous performers, handpicked by Littlefeather, performed an “honoring song” and an intertribal powwow dance. Finally, the museum’s director, Jacqueline Stewart, announced “the moment we’ve all been waiting for”: an appearance by Littlefeather, who is now seventy-five.

Dressed in colorful Native garments, her hair parted in the middle, Littlefeather came out in a wheelchair, to ecstatic applause. Her eyes were still large and soulful. Sitting across from Bird Runningwater, the co-chair of the Academy’s Indigenous Alliance—something that most definitely did not exist in 1973—she spoke softly and deliberately, but she was full of good humor. “Well, I made it after fifty years,” she said, adding, “We’re a very patient people.”

In a nearly four-hour video interview released concurrently with the event, Littlefeather detailed her “inimical” early life. Her mother was white; her father, who was deaf and a violent alcoholic, was of White Mountain Apache and Yaqui descent. Her parents worked as saddlemakers, which taught her early on how to “recognize a horse’s ass.” As a small child, she had tuberculosis and spent time in a hospital oxygen tent. Her parents both suffered from mental illness and were unable to care for her, she recalled, so at age three she was taken to live with her maternal grandparents; this instilled a “frozen need for acceptance that would never be satisfied.” Her grandparents raised her Catholic, and her introduction to the movies was religious fare such as “The Song of Bernadette” and “The Robe.” In grade school, she received racist taunts and was seated at the back of the class. Around age nineteen, she began hearing voices and having a recurring nightmare that her father was coming to “knife” her; she attempted suicide and was put in a Bay Area mental institution for a year. Through “psychodrama,” she relived her early traumas and began crawling out of a “deep black hole.” She was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia (she was later recategorized as schizoaffective bipolar) and has been in treatment ever since.

The ugliness of her relationship with her father had cut her off from her Native heritage, and it wasn’t until she joined the intertribal occupation of Alcatraz, which lasted from late 1969 to mid-1971, that she got to know “the beautiful side of things,” meeting activists and elders and learning to “reclaim what was lost.” She modelled for department stores and did some ads, but “I got tagged with the word ‘exotic,’ ” she recalled. It was activism—including a successful campaign to get Stanford University to drop its “Indian” sports mascot—that gave her purpose. She had noticed Hollywood stars taking an interest in the Alcatraz protests, including Brando and Anthony Quinn, but some seemed to be using the activists to research roles. Walking through the San Francisco hills one day, she came across Francis Ford Coppola, who had directed Brando in “The Godfather,” and asked for his help delivering Brando a “very sincere letter asking him if his interest in us was real.” Some time later, while Littlefeather was working at the radio station KFRC, a call came through for her. It was Brando. “It sure took you long enough,” she told him.

They hit it off, exchanging more letters and phone calls. Then, the day before the 1973 Oscars, Brando summoned Littlefeather to his house in L.A. and explained that, in the likely event that he won Best Actor, he wanted her to represent him. “I was just floored,” she recalled. There wasn’t much planning. When Brando asked if she had anything to wear and she said that she usually wore jeans and a T-shirt, he told her, “Well, you can’t wear that.” She said that she had a traditional buckskin dress from dances. “Wear that,” he instructed. While Littlefeather waited at his house, Brando sequestered himself to write his speech, taking his “sweet loving time,” she remembered. The ceremony was nearly over when Littlefeather, accompanied by Brando’s secretary, arrived at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, bearing Brando’s official invitation. A guard called over the evening’s producer, Howard Koch, who looked at Brando’s lengthy speech, pointed to policemen, and warned Littlefeather, “If you read that speech and you go over sixty seconds, I will have you put in handcuffs.”

She took her seat during a commercial break, moments before Brando’s name was called. The actor had made her promise not to lay a finger on the statuette. “I had prayed to my ancestors to be with me that night,” she recalled at the Academy Museum event. “And it was with prayer that I went up there. I went up there like a proud Indian woman, with dignity, with courage, with grace, and with humility. And, as I began to walk up those steps, I knew that I had to speak the truth. Some people may accept it, and some people may not.” One of the presenters was Liv Ullmann, her favorite actress, which made it even harder to keep her cool. (She was “eh” on the other presenter, Roger Moore.) She surveyed the star-studded crowd, which looked as white as a “sea of Clorox.” As she spoke, she heard a commotion backstage, which she later learned was John Wayne having a fit. (Littlefeather repeated the detail that Wayne had to be held back by six security men, though that part appears to be a Hollywood embellishment.) Backstage, she passed people doing war whoops and tomahawk chops. Accompanied by armed guards, she continued “walking in dignity” to the press rooms, where she shared Brando’s speech in full. Outside the theatre, she found Brando’s nephew and his friend waiting in a Cadillac, a guitar tossed in the back seat, and they whisked her away. “Congratulations,” Brando told her when she got back. “You did well.”

In the aftermath, Littlefeather claimed that she was “red-listed” from the industry. She believes that the F.B.I. planted smears and pressured the studios not to hire her. Although activists such as Coretta Scott King and Cesar Chavez voiced their support, friends told her that the late-night talk shows were warned not to have her on as a guest. “They could talk all about me, but I had no voice to talk for myself,” she said. “So I became a gossip item.” At one point, she recalled, she was at Brando’s house and two bullets came through the door, just missing her. She appeared in a handful of films through the seventies, but she drifted away from show business. After her lungs collapsed “like two flat tires on a freeway,” she recovered at a clinic and went on to study holistic health and work with Indigenous AIDS patients. In 2018, she announced that she had Stage IV breast cancer. Onstage at the museum, she said, serenely, “I’m crossing over soon to the spirit world.” Raising a finger, she said that she is not afraid to die, and that she has been giving away her possessions, including her car. “Before I leave, I’ll have nothing, not even this body I live in.”

After the conversation, the Academy’s current and most recent presidents, Janet Yang and David Rubin, came out. “Rewatching that clip was painful, and I’m sorry for what you’ve had to endure,” Yang said, going off script. Rubin read aloud his apology letter, which concluded, “You are forever respectfully ingrained in our history.” The gesture, however powerful, could only hint at the larger injustice: Hollywood’s dehumanizing depiction of Native Americans in one of its defining genres, the Western, and an absence of Indigenous stories that persists, despite such notable exceptions as the FX series “Reservation Dogs.” This was not the first time the Academy has tried to right its historical wrongs. In the eighties and nineties, it held small ceremonies to reassign Academy Awards to screenwriters who had been blacklisted in the fifties, including the writers of “The Bridge on the River Kwai,” Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, and the writer of “Roman Holiday,” Dalton Trumbo. But those honors were given posthumously, accepted by the men’s widows. For Littlefeather, the acknowledgment, belated as it was, came before it was too late for her to see it. The fact is that she’s been ingrained for nearly five decades in the Academy’s history—and, for that matter, in “The Godfather” ’s history. As an Italian immigrant in a hostile new world, Brando’s character, Vito Corleone, builds a dark alternative to the American dream; Littlefeather, much more peaceably, crashed an institution predicated on élitism and wrote herself into its story.

Onstage, Littlefeather, reading from notecards, accepted the Academy’s apology, not only for herself but “for all of our Nations.” She asked the Native audience members to stand. “Please, when I am gone, always be reminded that, whenever you stand for your truth, you will be keeping my voice and the voices of our Nations and our people alive,” she told them, placing a hand over her chest. “I remain Sacheen Littlefeather.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com