A peculiar calm punctuates many of Brian Finke’s images of amateur hand-to-hand bouts on scratted patches of grass in the Harrisonburg, Virginia area. Amid the portraits of breathless tussles and their bloodied aftermath, there are young male protagonists caught in moments of winded vulnerability and stunned submission. At times, the corner of the ring is a knot of resentment—tattoos, shaven heads, sharp looks at the opposition—and at other moments a study in self-doubt. In one of the most affecting images, a tousle-haired, bare-chested youth faces the camera and flexes his biceps—but his face is angelic.

Finke started taking these photographs in 2016, after he found himself warmly welcomed by the organizers of Streetbeefs, an anti-gun-violence project set up eight years earlier, in a Harrisonburg back yard, by Chris (Scarface) Wilmore. Wilmore, who’d learned to box while in juvenile detention, lost a friend to a local shooting. He hoped to provide his community with a forum where disputes could be resolved peacefully or else played out in the ring—his slogan is “Guns Down, Gloves Up.” The project’s YouTube channel has a few million subscribers, and many fighters now arrive in Virginia with more than personal grievance on their minds, hoping that online notoriety might lead to a career in boxing or mixed martial arts. But Wilmore’s principles remain in place: nobody pays or is paid to fight or attend. And the invitation to the parties at war—over money, sexual rivalry, real or imagined slights—is still there: “This is a brotherhood/sisterhood of like minded people who love fighting, fitness, and who hate gun violence.” (In practice, the sisterhood is mostly on the sidelines.)

In addition to YouTube videos, there are numerous images online of Streetbeefs fights and the scenes surrounding them. Mostly, these photographs keep some distance from the bout itself, giving us a wide view of fighters, ropes, eager crowds, trees and clouds in the background. Finke, in contrast, is in the ring, alongside a referee, so close to the action that the faces of the fighters are often reduced to sweating or dusty flesh, the occasional gout of blood. Finke uses flash even in bright daylight (an assistant is in the wings), which has the effect of isolating the fighters when other bodies are visible, too—the black-clad referee interposing himself, spectators lined up behind the ropes—so that here, too, in the middle of a bout, a stillness reigns, as perhaps it does in all sports, if that is what this is, violent or not.

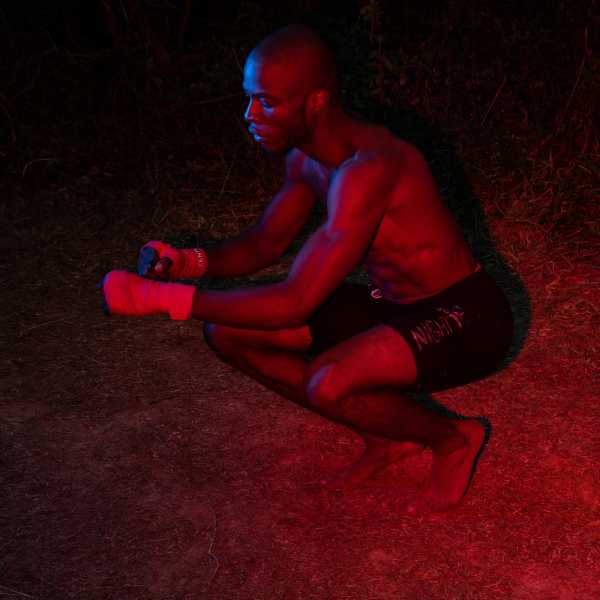

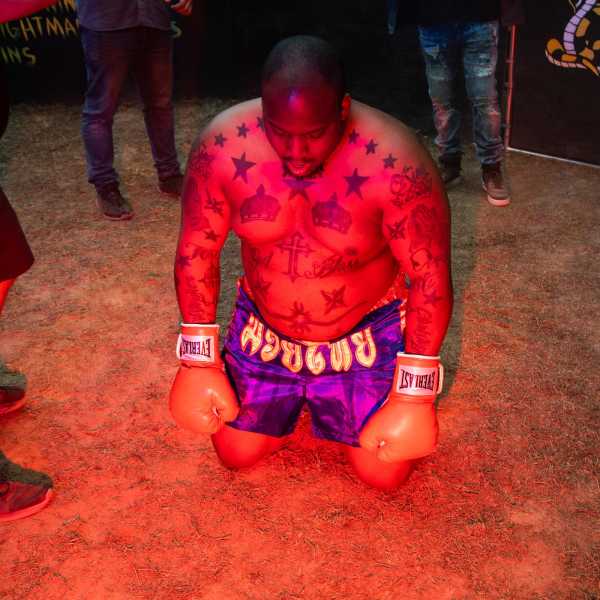

In a new book of his images, “Backyard Fights” (Hat & Beard Press), Finke supplements some of the pictures with the subject’s biographical details and a short quotation. Justin Craun, a young man in his twenties from Harrisonburg, says, “You can go in the yard, give your all, and walk out of there, and you’re both hugging and shaking hands at the end—win or lose.” Others focus on their own physical performance, on the release of tension and anger, on the bracing experience of failure in the ring. Leonidas Fowlkes, a warehouse and store merchandiser from Front Royal, captures something else: “I have tattoos. I have dreads. I’m African American. I get a perception. People judge me and think I’m just wild or just don’t care. But I feel like I’m an angel, I feel like everybody’s an angel in the world.”

Finke’s photographic equivalent for this feeling of transcendence is his bathing of nighttime fights in colored light. He told me that the red, blue, green, and purple gels are meant to render starkly lit scenes “more digestible.” The men look monumental, for sure, but also possessed by an interiority that is not just the red mist of their anger. In some of the book’s final shots, fighters appear with eyes shut, receding into sculptural attitudes of relief or reflection.

Finke grew up in Houston, Texas. As a teen-ager, he was introduced by a teacher to the photography of W. Eugene Smith, whose lowering black-and-white documentary studies may seem some distance from Finke’s work. (The one boxing photograph of Smith’s that I know is a playful picture, from around 1940, in which Sugar Ray Robinson looks down at a vanquished opponent, reduced to a pair of comically airborne boots.) But a fundamental interest in storytelling connects Finke to his first influence. “Backyard Fights” is the latest in a line of what he calls “obsessive” projects that have unfolded over years. Others have included cheerleaders, construction workers, flight attendants, and U.S. marshals—starkly lit series in which individuals and communities both inhabit and act out their roles.

Alongside the fighters, there is a second community in “Backyard Fights”: those who have come to watch the tense male camaraderie. Friends, lovers, family, many of them women—sometimes you can read their motivation clearly, as in the case of a shirtless boy’s proud mother, who stands smiling at the edge of a picture while he kisses his girlfriend. In others, the spectators’ attitudes are enigmatic. What are they thinking, the barefoot woman with her phone, another who raises a child for a better view, the girl who stares at the camera from behind a wire fence? Impossible to know whether they’re thrilled by the bloody scene or simply relieved at the diversion from more lethal forms of violence.

These photographs are drawn from “Backyard Fights.”

Sourse: newyorker.com