Who could forget that famous scene from “The Godfather” in which the Mob boss’s consigliere puts the bloody head of a racehorse named Khartoum into a Hollywood producer’s bed? Or that other gem, when the boss’s dandy henchman menaces a potential government witness by threatening to steal his fluffy white Coton de Tuléar service dog named Bianca? (“I am so ready,” the henchman says. “Let’s get it on.”) Bada-bing, American cinema at its finest!

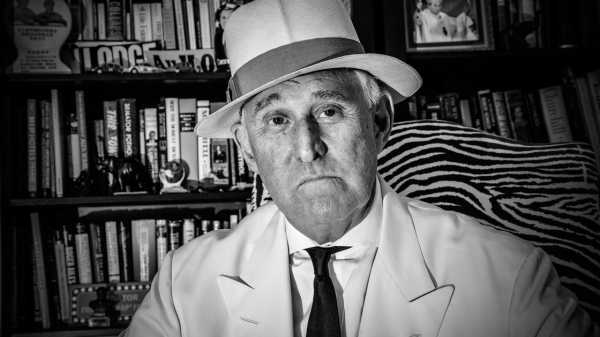

If that second example doesn’t ring a bell, it’s because it comes not from Francis Ford Coppola’s crime epic but from the shabbier story unfolding in Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian meddling in the 2016 Presidential election. On Friday, in a multi-count indictment of Roger Stone, the shady political fixer and longtime adviser to President Trump, prosecutors allege that, among other things, Stone called Randy Credico, an estranged associate (identified as “Person 2”), a “rat” and said that he would “take that dog away from you.” (Stone also allegedly told Credico, “Prepare to die.”) Last September, Stone admitted to threatening Bianca, whom Credico brought with him to testify before the Mueller grand jury, but claimed, “I did so out of concern that because of Credico’s substance abuse and his indigence, the dog was receiving neither food nor medical attention.” While making this claim, in a video he released online, Stone was holding his own tiny dog, a Yorkie named Pee Wee.

Let your mind travel, for a moment, to the image of Marlon Brando as Vito Corleone, holding a tiny kitten in his lap during the opening scene of “The Godfather,” if only to remind yourself of the gaping chasm between the elegance of those movies and the tackiness of this real life. Despite the disparity, Stone seems keen to imagine himself as a grand figure in the Corleone saga. According to the indictment, Stone also suggested to Credico that he “should do a ‘Frank Pentangeli’ ” during his testimony before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. The reference was to a character from “The Godfather: Part II,” who “testifies before a congressional committee and in that testimony claims not to know critical information that he does in fact know.”

That’s a handy summary written by some cinephilic member of the Mueller team, but here’s a bit more. In the movie, Pentangeli, who is played by the actor Michael V. Gazzo and goes by the nickname Frankie Five Angels, runs the New York operations for the Corleone family. After a dispute with the boss, Michael, played by Al Pacino, Pentangeli is nearly murdered. He thinks that the hit was ordered by Michael, and so he agrees to enter witness protection and testify against the don in the government’s ongoing Senate investigation of the Mafia. (They were trying to get Michael on perjury.) But on the day of his testimony Pentangeli’s brother Vincenzo arrives in the hearing room, looking sad and a bit baffled, having been hustled over from Sicily by the Corleone family to sit in the audience. Vincenzo’s appearance gives Frank cold feet, and he recants his earlier sworn statement, saying, “I don’t know nothing about that,” and adding that he made up a lot of stuff to get a deal from the F.B.I. The hearing adjourns into chaos.

Every two-bit hustler in America seems to love the “Godfather” series, and most, especially the ones who get arrested by the F.B.I. in early-morning raids on their homes, learn the wrong lessons from it. You can see the appeal of the Frankie Five Angels moment for the likes of Roger Stone. After looking his brother in the eye, Frank can’t bring himself to rat out the family. The pesky government, reaching for a perjury charge, gets thwarted by the old omertà codes of honor and loyalty. Later in the movie, when Michael’s wife, Kay, asks what really happened in the Senate hearing, he tells her, of Frank, “His brother came and helped.” Kay asks, “All he had to do was show his face?” Michael responds, “It was between brothers, Kay. I had nothing to do with it.” For years, tough guys everywhere have seen this moment as one in which one brother helped another to do the right thing.

But Michael, of course, is a liar. If Frank had testified against the Corleones, his brother Vincenzo and his children would have been hunted down and killed. All the movie’s oft-quoted axioms—“Don’t ever take sides against the family,” etc.—are bunk, made clear by the fact that Michael routinely kills family members who betray him. (See his brother-in-law Carlo and, of course, his brother Fredo, whose death in a dinghy on Lake Tahoe marks the story’s final descent into tragedy.) The cold truth of that moment in the Senate hearing emerges later in the movie, when Michael’s lawyer and adopted brother, Tom, visits Frank in jail, and the two men negotiate a grim compromise. Speaking of Roman times, they reflect that when someone made a failed move against the emperor, a person’s family might be spared and looked after—“taken care of,” as Frank tells Tom—if that person went home quietly and killed himself, making no more trouble. And so that’s what Frank agrees to do. “Don’t worry about anything, Frankie Five Angels,” Tom tells him. The last time we see Pentangeli, he’s dead in a bathtub, having slit his own wrists.

You can see why Stone’s suggestion to Credico might have seemed less than appealing, and even menacing. The subtext here, if we want to call it that, is that there must be a kind of screw-you-copper honor among thieves. The problem for the likes of Stone, Credico, and all the other “Godfather”cosplayers out there—those adjacent to Trump and elsewhere—is that they forget that there is only one boss, and it ain’t them. They are further down the ladder, exposed and expendable. These men imagine themselves to be regal antiheroes—to be the Vito or the Michael of their story. Really, they’re just the Fredos and the Frankies.

Sourse: newyorker.com