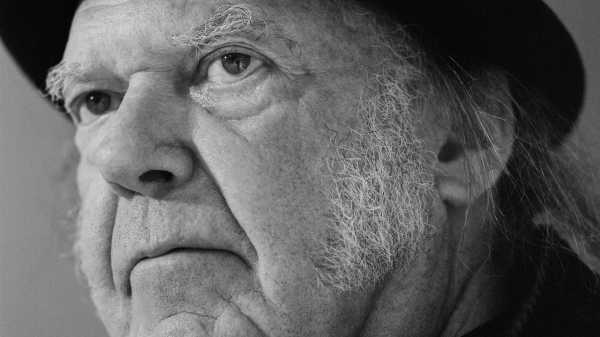

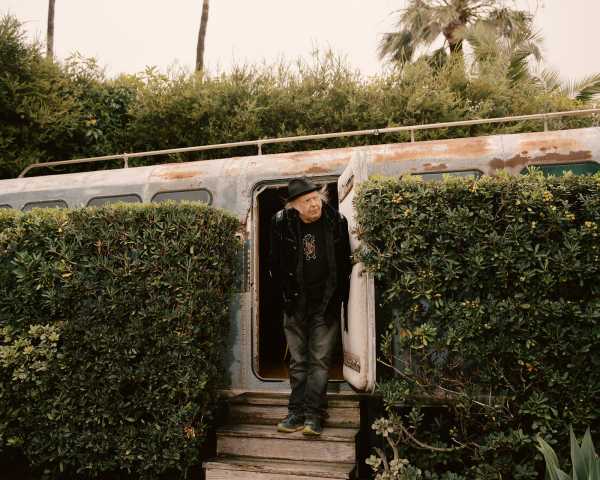

Since 1968, Neil Young—who was born in Toronto in 1945—has been making raucous, astringent guitar music, both as a solo artist and with his longtime backing band, Crazy Horse. On occasion, he has veered toward tenderhearted folk rock, as a member of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and on records such as “Harvest,” his fourth LP and the best-selling album of 1972. Young has spent most of the past fifty years arguing for environmental causes, even (or especially) when nobody was keen to listen. On the title track of 1970’s “After the Gold Rush,” he dreams of a climate apocalypse, spaceships zooming across the Earth to gather and repurpose its bounty: “Look at Mother Nature on the run / In the nineteen-seventies,” he sings, his voice high and splintering. My favorite version of the song was recorded live at Carnegie Hall, and features just Young’s voice and piano. It sounds like both a lament and a warning.

Last week, Young released “World Record,” his forty-second studio LP, and an album focussed almost exclusively on how to combat climate change. Young described the experience of writing it as almost supernatural: he was taking daily walks through the Rocky Mountains, where he spends time with his wife, the actress Darryl Hannah, and found himself whistling unknown melodies, which turned later into stories. None of it felt like his own, exactly. “It seemed to me like each one came from a different spirit, as day after day I walked through the trees and the snow with my two dogs running around,” he told me recently, on a Zoom call from an office in Santa Monica. He was wearing a black T-shirt with a drawing of a human heart on the front. “A different melody with a different feeling must be coming from a different person,” Young said. He was simply in the right place to receive the songs.

There’s a visceral spontaneity to all of Young’s music, which has now become the hallmark of his work—a very deliberate, very human embrace of imperfection. Perhaps “imperfection” is too judgmental a word; the performances are real. “World Record,” which was co-produced by Rick Rubin, was recorded live and mixed to analog tape. In a post on NYA Times-Contrarian, Young’s Web site, he wrote, of the sessions, “Real magic lasts and we think we have it.” This conversation has been condensed and edited.

“World Record” has a looseness and a spontaneity that’s rare in new recordings. It reminds me a little of listening to old 78-r.p.m. records—most early recording artists had just one three-minute shot in front of the microphone, and sometimes things got a little wild, a little free. How do you purposefully cultivate that feeling in the studio?

I think it has to be an accident. One thing that many people have said about this record is that it sounds like it’s coming from another place or time. It’s not really relevant to the last record or the record before. I came up with the melodies for eight or nine of these songs while going on walks. You know how you do. You might be taking a walk with the dog or something, and you start whistling a tune. Maybe it’s not a tune you even care about; maybe you’re imagining you’re seeing a parade somewhere, and this is what the band is playing. Then I said, wait a minute, I’ve got my phone—which is a funky old flip phone, with a really funky camera in it—and I turned on the camera and made a movie while I was walking along, whistling this melody. That kept happening for weeks. I’d take my little flip phone with me, and record anything that I started whistling and didn’t know what it was. No words, no instruments, no tones, no chords—just the rhythm of walking, and whistling. And that’s how it started.

Then I was in Malibu, thinking about recording with Crazy Horse. I remembered that I had these whistling things in my pocket. I started listening to them, and I just banged out lyrics—I never corrected anything, except for my spelling, which is awful. I was using a computer instead of writing by hand—I never use a computer, so that was weird—and I’m listening to this guy whistling a melody, and I’m making up words. It was almost like I was writing with somebody.

It sounds as though you’re describing a metaphysical experience, almost—a channelling.

Yeah, exactly. Very flow—it was very flow. I did all eight songs in two days, and never changed a word. Maybe I’d put a chorus in, or move it to another place. I called the studio, Shangri-La, and booked it. I love that place. I said, “I’d like to start around the first of May.” It was April, the full moon, that weird blood moon—that’s when I was writing these songs, writing all the words. I looked at the schedule for the next month and started figuring, well, if we get in there a couple of weeks, maybe twenty days ahead of the next full moon, we’ll all peak at once. It worked.

When you were out walking and whistling, how did the landscape and its ambient music make its way into those melodies?

I was walking down a snowy trail, up and down hills, and through a beautiful pine forest. A blight had killed all of the aspens—there were millions of them, everywhere, dead. No one knows why. Anyway, I’m walking along, with these trees that are dead or dying, and then there are pine trees coming up among the dying trees. These little baby pines, Ponderosa pines. They’re incredible trees; they’re so beautiful. I’d be walking along, whistling and recording on my little phone, and every once in a while, I’d stop, and think I could hear a rumbling. I’d try to catch it. It was just a super-low-frequency thing in the ground. I don’t know what that was, and I still haven’t been able to figure it out.

How did you prepare to take the phone recordings into the studio with Crazy Horse?

The first thing I’d do in the morning was have a little coffee and do a verse and chorus of a song. I had to learn the chords. I was playing the pump organ or piano, sometimes a guitar. I would do a verse and a chorus of a song, and send it to Billy [Talbot], because he plays bass and has to know the changes. But I wouldn’t send it to Ralph [Molina] or Nils [Lofgren]. Ralph never listens anyway. He might listen, but probably not. Nils would learn it too much. So I held off on anyone else getting it. I covered all eight songs, and found the chord changes and the keys and the instrument. So, now I have got the recording from the phone camera, where sometimes you see the dogs running by my feet as I’m walking along, and I have this other recording, which I made for the guys.

When we were ready to go, I called Rick [Rubin]. Rick and I had worked together in the past—we really like working together, and we have a lot of fun anytime we’re doing anything. I called him and I said, “Listen, I booked the studio. Are you around?” He had been in a house fire, where he was caught on the second floor. He had suffered from smoke inhalation, so his voice was all crazy, but he said, “Yeah, I want to come to the studio—we’ll hang out.” He’s speaking in this low voice. So that’s how it was approached.

I especially love the pump organ on “Walkin’ on the Road (to the Future)” and “The Wonder Won’t Wait”—it adds this wheezing, groaning sound. It’s almost as though another person, another set of lungs, is suddenly in the room.

It’s a beautiful machine. It’s got the pumping, and the air moving through it, and the volume. If you only use one note, the volume’s louder than if you use two notes. Everything changes as you play it, because you’re letting air out. I’m not really very good at it. I play it, but you can tell that I really don’t know what I’m doing.

It sounds as though you and Rick Rubin have unusually compatible approaches to recording. What in particular have you liked about working with him?

We make chronicles of things. Or I do—I make chronicles of an experience. I play the songs, and we’re doing it live, and everything happens, and then we capture it like that. Rick is a genius. It’s so easy, because he loves music. You’re not gonna find a person who loves music more than Rick. He’s dedicated to preserving it. If you talk about an environmentalist trying to save the Earth, then he’s a music-mentalist. That’s the way he looks at music. That’s a great thing. He’s just living it. He’s made some really cool records in other genres, but they’re all the same thing to him. It’s all music. We worked on it together every day, sitting on the couch, listening, making changes. As soon as we start getting tired, we leave. We don’t work hard—we work until we’ve done something, and when we feel good about how far we’ve gotten we leave and come back. He’s into the flow of things. That’s how he likes to live his life, no matter what he’s doing. We have a lot in common in that respect.

Many of the lyrics here are sort of optimistic—or, at least, they suggest that if we love well, and love selflessly, if we take care of each other and the planet, anything is possible. Have you had to work to arrive at this place of hope?

Yeah. In a natural kind of way, without knowing it was happening. I’m conscious of what’s going on in the world all the time. But these songs are from different people. They’re all me, but they talk about different things, and they come from different places. I don’t feel connected to the whole vision of the record in the same way—it’s got all these characters. The point of view of “Love Earth” and the point of view of “Break the Chain” are so different. It’s not the same thing, but it is the same thing. I don’t want to go too off the deep end with this. There’s whistling coming out of a forest somehow; there’s an entire dead species of tree right there in front of you, and not just a few trees, it goes for miles and miles. So, with that background, and then knowing what’s going on in the world . . . I don’t like to dwell on it much, but I think everybody’s terrified.

Yeah, I’d say so.

But they’re not terrified about politics. They’re terrified, period. Because of [climate change], and how we’re not dealing with it. You’ve got all those TV networks, warring personality against personality, building this side against that side, blowing everything up into the latest episode of whatever what’s-his-name is doing, how they almost did this to what’s-her-name’s husband. . . . Just on and on and on. The reason everybody’s so uptight about the things they’re talking about, in my view, has nothing to do with what they’re talking about. I think it has to do with what’s happening to the planet. That’s what I think. So that’s where I go.

We haven’t quite realized that [climate change] doesn’t care. It’s a little bit like a virus. It doesn’t care. It has a thing that it does, and it’s doing it. This is not a sci-fi movie; this is real. Just because it’s science doesn’t mean that you can ignore it. But we compartmentalize it. We don’t look at the situation the way we should. I can envision the Chinese guy, the Russian guy, the American guy, the German lady, the leaders of all these countries, the guy from South America, all these people onstage together, talking, one by one, in their language, to the world, with subtitles underneath. We have to get to the point where we all come together, and we realize that we’re all on the same Earth, and there’s one way we can fix it. We need to grow food, and we need to grow fuel. Imagine if, instead of dust rising into the sky, the carbon started returning to the Earth. Animals on the ground, instead of being in little metal cages with antibiotics and fans, on top of each other so they can make it to the supermarket.

For some musicians, the idea of making art in the midst of a crisis—during the pandemic, say, or in the face of an ongoing climate catastrophe—can feel small, or silly, or inconsequential. It’s the artist’s imperative to make work that’s personal and important to them, but then there’s also this larger question of whether art can help solve problems. Can it?

Well, I have a plan. I’ve been working on it with a couple of my friends for about seven or eight months. We’re trying to figure out how to do a self-sustaining, renewable tour. Everything that moves our vehicles around, the stage, the lights, the sound, everything that powers it is clean. Nothing dirty with us. We set it up; we do this everywhere we go. This is something that’s very important to me, if I’m ever going to go out again. . . . and I’m not sure I want to, I’m still feeling that out. But, if I’m ever going to do it, I want to make sure that everything is clean. What was the last thing you remember eating at a show, and how good was it? Was it from a farm-made, homegrown village? I don’t think so. It was from a factory farm that’s killing us. I’ve been working on this idea of bringing the food and the drink and the merch into the realm where it’s all clean. I will make sure that the food comes from real farmers. Once it’s up and going, and I’m finished with my part of the tour, there’s no reason why the tour has to stop. The tour can keep on going with another headliner. It’s about sustainability and renewability in the future, loving Earth for what it is. We want to do the right thing. That’s kind of the idea.

In the documentary about the making of “Barn,” your previous record, I spotted a light-up sign in the barn where you recorded that simply reads “LOVE.” To what extent is love—romantic love, familial love, love of the planet—a guiding force in your work?

Well, it’s a very positive feeling. Sometimes it results in anger and other bad feelings because it’s mismanaged—that’s life. But everything that I try to do is based on positive feelings. There must be a way to effect change. There has to be a way to help. I don’t think it’s gonna be by yelling at people or calling people names. It doesn’t mean your politics have to be the same as somebody else’s. It’s just everybody getting together to do this. That’s why a lot of these songs talk to people as though they’re a group.

The idea of “we,” of the collective, is a powerful presence on the new record. Western culture, with its enduring emphasis on the individual, has led us to believe that grief and love are personal feelings. Yet something about your lyrics points to a different mode of understanding—that love and grief are universal, shared. I love the chorus of “This Old Planet,” which contains a very simple but very profound assurance: “You’re not alone, on this old planet.”

Thank you. Well, I feel it, too. We need to come together. That’s all I know. When the virus hit, everybody was terrified. They didn’t know what to do. How could it shut everything down? And then the next thing that happened is “Wow, have you seen how many birds there are?” In cities, people were seeing things that they never saw before. The planet was talking to us. We didn’t even know it was happening; we were so focussed on the virus. But remember how people would talk about the birds in their neighborhood, how they never knew there were so many birds, and now they’re all singing? And the sky is pretty?

This is your second new album in less than a year. To what extent do you think your new music is in conversation with your old music, or that your current self is in conversation with your past self?

Well, in this case, very little. Because the songs came from not thinking. They came from another place. I just picked them up walking in different parts of the forest. It’s a whole bunch of people singing about what seems to be a common situation. I can’t disassociate myself from that experience and say that I wrote this or I wrote that. It just doesn’t make sense to me. It’s pretty different from what I did in the past. For me, it was more like a gift—I had to work on ’em, but they just came to me from all kinds of places. I don’t know what that means, but I hope it happens again. I like it.

The album art features a beautiful photograph of your father. Where and when was that picture taken?

I think that was taken in the fifties, probably Toronto. My dad was working for the Toronto Globe and Mail at the time. He’s just walking down the street. It’s a great picture of him. There’s somebody who knows where they’re going!

Your father was a sportswriter, and also wrote novels. Did you learn about storytelling from him?

He called me Windy—that was what my name was, as far as he was concerned. He had a routine. In the afternoon, I would go up into the attic of our old wooden house, up all the steps, to get to the fourth floor. It had a couple of windows that looked out onto the roof. He’d be up there at his desk, papers everywhere, bangin’ it out on this Underwood typewriter. I walk in and he’d say, “Hey, Windy, what’s goin’ on?” “Oh, nothing, Daddy, just want to say hi.” And I’d hang out there for a while, and he’d just go back to writing. He’d say, “If I come in here and I don’t have anything to write, as soon as I sit down, I know what it is.” He imparted that on me.

Why did he call you Windy?

I don’t know. [Laughs.] He called me Windy. Wind blowing through my head, I think that’s kind of the message.

In the liner notes, you included the birth date of everyone involved in the making of “World Record.” What inspired that?

It’s a record of things that happened, and this is information about the participants. I stepped back and looked at it that way, and I just stayed with it. You see a picture of my mom and me looking at each other, my sister and my brother, all of ’em are in there, and they’re all an important part of my life. These are the thoughts of these people I was channelling; this is where all this came from.

So much of what we’ve been talking about feels tied, to me, to the idea that it’s incredibly easy to lose touch with one’s humanity while participating in the modern world. But there’s something about looking at someone’s birth date and remembering that we all arrived here in the same way. We weren’t; then we were.

We’ve got a number.

You maintain an incredible archive of your work online. A couple of years ago, you encouraged Joni Mitchell to do the same. How long have you been friends?

We’ve been friends since we were twenty. She has a massive collection of stuff; I just suggested that she get it organized in a certain way. I had this tool, and if she wanted to use it she could. So she’s been going ahead and she’s been doing that organizing. She’s making progress. She’s doing it in her own way. She’s not using the same type of approach that I used, but she’s getting to the same place. She’s got a lot of paintings, an unbelievable art collection, beautiful works of music and poetry. She’s a real artist.

Have you ever found yourself sort of drifting toward another way of making art?

Not really. I dabble around in painting watercolors, but only every once in a while. I did some art work of my favorite cars. I drew all the cars and painted them. That was fun.

You’ve been playing guitar for more than fifty years. Are you still learning things about the instrument?

Always. I really don’t think much about it anymore. When we were playing these songs, I heard myself doing stuff that I’d never done before, but it all seemed like it was a natural thing to do. That’s cool.

Have you ever had writer’s block?

No. I never have. I don’t do that. If that happened, I’d go somewhere else, work on something else. I do other projects—I’m building an outdoor model-train layout, which has been a lot of fun. It just takes me away into another world. There’s no pressure to it. I have a buddy who helps me build it. We spend days and days and days and weeks and months on these. If you’re stuck, you’ve got to get out of it. You’ve got to get way out of it.

At seventy-seven, have you thought about retirement?

Doesn’t seem out of the realm of possibility. That could happen. You get to a point in life where things are happening everywhere around you, and your friends are going away and not coming back. Things change. We finished recording this toward the end of May. That’s six months ago. That’s a long time for me to wait. I’ve never waited that long to put out a record.

Pressing-plant delay?

The vinyl. It takes so long. Because the record companies, in their ultimate wisdom, seeing what a great thing digital was, they sold all the places where they made records. Now people want records and they haven’t got a facility to make them in, so it takes months and months and months to get vinyl. Vinyl is ultimately much better.

You’ve said that music—when it’s good, and when it’s played on a proper stereo—“sounds like God.” You’ve also been a vocal opponent of Spotify. In April, you pulled your music from the platform. Was that a difficult decision to make?

No. I didn’t even think about it much. I woke up one morning and I was reading a story about how all kinds of people were dying in hospitals because of misinformation about COVID. They were making bad decisions, and it was [coming from] this guy on Spotify. I’m goin’, “What the hell, the guy’s on Spotify? And he’s giving bad information about COVID, like that doesn’t matter?” I didn’t even think about it. I just told my management, “Just pull me off of Spotify—I don’t want to be on Spotify anymore.” It seemed like a cut-and-dried thing to me. I don’t know the guy’s name. He’s there, and I just told them, “If that stays, I leave.” Whatever they want to do, that’s fine; I just don’t want to be part of it. I don’t want to have my music playing there.

Was there any resistance from your management?

They all supported me one hundred per cent. They all knew what I didn’t know, and still didn’t really care. At this point, it doesn’t matter to me.

This December, you’re reissuing “Harvest,” on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary. You were just twenty-seven when “Harvest” was first released and went to No. 1. To me, there’s a through line, lyrically, to “World Record,” insofar as both albums are a little bit about time. In a way, all of your work is about time.

Something about it is the same. But I don’t know what it is. “Old man, take a look at my life”—I could write that for me, for somebody else, for one of those guys whistling in the forest. Who knows? I don’t know. I’m happy that that was a big successful record, and I have no idea really why.

I have found that “Harvest”—as well as “World Record,” and so many of your records—is a very fine companion. Your music has brought me a lot of comfort.

I’m very happy to hear that. That’s wonderful news. Thank you so much. That’s what music is good for. If the feeling is good, you can take it with you. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com