The current row over the place of slavery in American history provokes long-standing anxieties over the nature of the country itself. For a nation that views itself as exceptional in its quest for freedom, justice, and liberty, its origins as a settler-colonial state built on the bodies of enslaved Africans are necessarily fraught. How do we make sense of the American creed of liberty, equality, and justice alongside a reality of enslavement and the legal subjugation of Black people? Answering this question casts doubt on the sagacity and the morality of the Founding Fathers; it also guts the premise of unfettered social mobility, which supposedly underwrote the American dream for the “greatest generation” of the twentieth century.

The latest flash point has been in Florida, where, in January, Governor Ron DeSantis rejected a proposed Advanced Placement course on African American studies, sponsored by the College Board. Officials in Florida, who claimed that the proposed A.P. course “lacks educational value,” rehearsed similar arguments in 2021, when the state banned the educational use of the 1619 Project. Created by the Times Magazine staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones as an exposition on the meaning of slavery in American life, the project was published in 2019, to mark four hundred years since the first Africans arrived in the colonies that would become the United States. Hannah-Jones’s lead essay, “Our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written. Black Americans have fought to make them true,” won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for commentary and, perhaps more than any other element of the project, generated controversy and then denunciation. Hannah-Jones’s provocative assertion is that slavery, and the racism that it unleashed to justify the institution, are foundations of American society. She goes on to argue that, to the extent to which the U.S. is a democracy, it is because of the struggles of Black Americans for inclusion into the mainstream of American society, efforts that expanded the rights of other socially marginalized people. Hannah-Jones then pushed her provocation further, arguing that the American Revolution was in part inspired by the desire to preserve slavery.

A small band of dyspeptic historians, along with outraged Republicans, decried and denounced the project as historically inaccurate—dangerously so, it seemed, from their heightened response. More objections to the project came from across the ideological spectrum. The Northwestern University historian Leslie M. Harris had been contacted by the Times to fact-check the notion that slavery was a driving purpose of the American Revolution. Harris rejected the claim, but the argument still made its way into the 1619 Project. In the spring of 2020, Harris wrote that she generally supported the project, as “a much-needed corrective to the blindly celebratory histories that once dominated our understanding of the past—histories that wrongly suggested racism and slavery were not a central part of U.S. history.” But she was concerned about what she described as “inaccuracies” in the project’s characterization of slavery during that period.

Some of the criticism from the left was not just about the accuracy of certain points of emphasis, but also about Hannah-Jones’s determination to see slavery as the “original sin” that explains much of what is wrong today in the United States. As the historian Matthew Karp pointed out, “Whether the subject is Atlanta traffic, sugar consumption, mass incarceration, the wealth gap, weak labor protections, or the power of Wall Street, the burden of argument remains the same: to trace the deep continuities among slavery, Jim Crow, and racial injustice today.” The Times eventually made an edit to clarify the project’s claim about the extent to which protecting slavery motivated the Revolutionary War, but the emphasis on the ways that slavery has shaped nearly every aspect of our contemporary world remains.

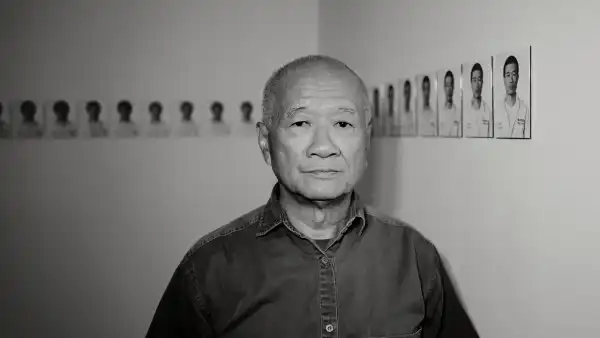

The 1619 Project has generated an award-winning book, podcast, and other ephemera—and now, since January, a six-part Hulu documentary series, with Hannah-Jones and Oprah Winfrey among the executive producers. The series takes up the same charge as the original project—demonstrating the ways that slavery has touched almost all aspects of American life, including Black maternal health, the design of Amazon factory warehouses, and policing. Hannah-Jones narrates the series, which also explores her own family’s history with racism, and she appears throughout. As the criticisms of the project reached full throttle, they often devolved into criticisms of Hannah-Jones herself. Now, she appears on camera, interviewing people, with notepad in hand, as if to remind us that she is, above all, a reporter and a storyteller.

The episodes—titled “Democracy,” “Race,” “Music,” “Capitalism,” “Fear,” and “Justice”—stand alone, but when taken together they paint a damning picture of American society. Hannah-Jones speaks poignantly to the ways that simply removing racial exclusion from the law was never enough to undo the damage caused by centuries of legal subjugation, economic marginalization, and orchestrated divestment from Black-majority communities. Indeed, the series makes the important point that the success of some African Americans has been used to “camouflage the truth that life for so many Black Americans continues to be defined by struggle.” The series is at its best when examining the relationship between race and class, debunking the misperception—particularly pronounced during the Trump years—that all working-class Americans are white. “Slavery, and the Jim Crow era that followed,” Hannah-Jones observes, “were at their essence systems of economic exploitation.”

In a society that still entertains the idea that Black social immobility is self-induced, Hannah-Jones’s determination to make slavery central to how we understand the nation’s history and the marginalization and oppression of ordinary Black people is welcome. But in her efforts to assert that slavery is the driving explanation for the particular problems that Black people face today, it is not always clear what the assertion adds to her argument. For example, the episode “Race” contains the heartbreaking story of a middle-class Black woman, married to a New York City police officer, who suffers the death of one of her twins in utero. Although the woman, Chrissy Sample, points to neglect by a racist or indifferent doctor as critical to her mistreatment as a patient, Hannah-Jones links her treatment to the vestiges of slavery. The episode makes important observations about how Black women’s sexuality and gender were shaped historically by slavery, documents the brutal treatment of Black women in the field of gynecological medicine during the mid-nineteenth century, and notes that Black women’s bodies continue to be pathologized. But in 1990, eighteen out of one hundred thousand Black women died in childbirth; for white women, it was five in every one hundred thousand. Today, those numbers have increased to fifty-five Black women and nineteen white women. Framing today’s prenatal health-care crisis as having an origin story in slavery does not tell us nearly enough about what has happened between 1990 and today, leading to the rapid rise in Black maternal mortality and a rise in the maternal mortality rates of white women as well. Moreover, Hannah-Jones makes the important point that Black maternal death cuts across social class, but we don’t get any explanation of how the fortunes of some Black women diverged from others. What happened?

Something similar can be said about Hannah-Jones’s discussion of the police. The “1619” miniseries powerfully presents the police as racist, menacing, and brutal, picking up the popular narrative that modern police forces began as slave patrols and that they developed their fear of Black gatherings because of these meetings’ potential for slave rebellions. This is certainly part of the history of policing in the United States, but it is not the only or even the most significant element. Police forces had also formed in major U.S. cities by the late nineteenth century, to maintain order amid the conflicts that developed around housing, workplaces, and the tumult of urban life. The historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad has skillfully shown that, at that time, the idea of Black criminality was largely shaped by census data showing, among other things, greater rates of Black mortality and imprisonment—rates that were shaped by factors like poverty and the racism of law enforcement. Practices that were certainly influenced by slavery developed fully in subsequent decades, in a rapidly evolving United States.

More important, the emphasis on slavery as the singular explanation for contemporary American racism can miss the role of struggle and social movements in forcing change. This isn’t the same as insisting that the U.S. is on an inevitable march toward progress, as President Barack Obama did when he said, in his 2004 Democratic National Convention speech, “I stand here knowing that my story is part of the larger American story, that I owe a debt to all of those who came before me, and that in no other country on Earth is my story even possible.” Instead, as the “1619” series also captures, police in the U.S. are often responding to building protests and anger in Black communities. Hannah-Jones interviews the Yale historian Elizabeth Hinton, who explains that, in the late nineteen-sixties, efforts to professionalize the police and arm them with military-grade weapons were in response to growing Black demands for better housing and jobs, and for relief from constant police presence. Moreover, according to Hinton, some of the military technologies used in the Vietnam War and the U.S. interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean were later transferred to police, who used them in Black urban communities. These were contemporary issues that developed in response to the migration of Black people from the rural South to urban enclaves across the country, and the overwhelming focus on slavery does little to illuminate them.

This is what is fascinating and, at times, confusing about “1619.” Taken together, the episodes knit a story about racism and inequality animating the entirety of American society. Yet for most of the series there is very little sense of what anyone can do about any of these conditions, because the overarching emphasis on slavery as the cause of racism blots out any understanding of the ways that change has occurred over time—change that is almost always wrought by social movements composed of ordinary people. In the end, two episodes point in very different directions than the series as a whole, offering hope for a better future.

The final episode of the series is called “Justice,” and it makes a stirring case for reparations. The basis for the demand is clear—through a combination of public policy and the practices of individuals and institutions, African Americans’ wealth, income, and opportunities have been pilfered and plundered, from the time of slavery to this present day. Hannah-Jones zeroes in on the racial wealth gap as the ultimate evidence of the bridge between historical and contemporary racism. She goes on to argue that, only by erasing that gap as a form of reparation, we can “acknowledge the crime” and “atone” for slavery, allowing us to “live up to the magnificent ideals upon which we were founded.”

Given all that the docuseries portrays about the deeply ingrained hardships that accompany life for Black Americans, the call to erase the racial wealth gap seems fair but anticlimactic. Reparations may address the harms of slavery and the century of legal racism at its end, but the searing episode called “Capitalism” shows that new injustices and harm are created every day, encoded into an economic system that clearly prioritizes profit over people. Here again, Hannah-Jones makes what feels like an awkward claim: that Amazon’s method of picking items and boxing them is a modern iteration of the plantation. It is also a metaphor that is undone by the presence of white workers throughout the Amazon warehouse. Yet the episode carefully and powerfully captures the struggle to unionize Amazon warehouses in Bessemer, Alabama, and Staten Island, New York, featuring Jennifer Bates and Derrick Palmer, two Black union organizers leading the efforts to organize Amazon. Hannah-Jones also delves into the lives of her family to help illustrate the fate of American workers. She interviews a cousin, Chimiere Tillman, who, after working in the same retail store for fifteen years, still made less than ten dollars an hour, while raising children. It was only once the government sent pandemic stimulus checks that her income finally increased. Tillman is the daughter of Hannah-Jones’s uncle, Edward Tillman, who worked in meatpacking and steel, had no health insurance, and died from undiagnosed cancer. Both Hannah-Jones’s uncle and her father, Milton Hannah, died before they were old enough to collect social-security payments.

Hannah-Jones asks the historian Robin D. G. Kelley what can be done to change the inequality that is a feature of capitalism. He explains that, among other things, “we actually need a critique of capitalism and how capitalism and racism kind of function together to oppress not just Black people but all of us,” and “we need to think seriously about solidarity.” Hannah-Jones captures the possibility of solidarity in footage of multiracial union rallies featuring Black organizers. It’s also on display in footage from the summer and fall of 2020, when millions of people spilled into the streets to protest police violence and the incompetent federal response to the pandemic, among other grievances. Those were not just protests of Black people but of disaffected white people as well.

Hannah-Jones points out that white workers have, over time, voted against their interests and chosen race over class. But it’s also worth saying that some white workers in some situations have acted in solidarity with their Black counterparts, even when these occasions have been fleeting or when the gains of such struggles have been overturned. Such solidarity is a necessity, because reparations can’t increase the wages of workers like Hannah-Jones’s cousin. Nor can they provide the health insurance or other benefits that might have prevented the premature deaths of her father and uncle.

More generally, Kelley is saying that we don’t have to only be imprisoned by the past. Slavery was central to the creation of the United States. But it was a system that was always changing in response to opposition, from the enslaved themselves, a burgeoning abolitionist movement, the Republican Party, and, eventually, the whole of society, when the Civil War became a revolutionary movement to end slavery in the Union. The interaction between people and institutions provokes constant struggles, big and small, and constant change. Nothing stands still, not even racism.

That, of course, is part of the fear of the white-nationalist right, which includes some of the G.O.P. After the protests of 2020 threatened to normalize the concepts of systemic racism, defunding the police, and reparations as part of the national reckoning, there was an effort to undermine them. The right’s success in reducing all of those revelations about racism in the U.S. to “making white people feel guilty” was also evidence that new ideas could be rolled back into old ones. But, whether the ideas are opening up or shutting down, that a flow exists at all speaks to the dynamism of society—for the better or worse. Hannah-Jones’s visually arresting and commanding distillation of race and class in our society speaks not only to the need for change but its possibility. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com