In my teen years, in the late nineteen-sixties, my father was adamant about cigarettes and sex. “I know a lot of teen-agers are having sex already, but if you hold off on having sex until you are eighteen, then we’ll get you the pill,” he said. “And don’t smoke cigarettes. They are bad for you.” We had a little deal, and I stuck to it. I didn’t have sex until I was eighteen. After I started the pill, though, I didn’t waste much time. Those were the days of free love. You’d just go and go and go until the bed broke or something. (The beds were cheap back then, at least the ones we were using.) I never did take to cigarettes, which I’m glad about, because not smoking has helped my singing voice mature. I don’t sound like I did when I was younger; it’s different, but just as good.

I’ve been called an “erotic” songwriter. I don’t disagree, but even though I had plenty of sex when I was younger, I was never promiscuous. The brain is the real erogenous zone, at least for me, so I have to connect with somebody intellectually and almost spiritually in order to be attracted to them physically, and that rarely happens immediately. I realized early in my adult life that talking—real, honest, substantive conversation—could be superhot, and it didn’t have to result in anybody taking their clothes off for it to be erotic in a lasting way. Very often a good conversation is more memorable than fucking.

As I was growing up, I began to be attracted to a certain kind of man, and I would maintain that kind of attraction for the rest of my life. The way I’ve often described this kind of man is “a poet on a motorcycle.” These were men who could think very deeply and have very deep feelings, but who also had a kind of blue-collar, roughneck quality to them. For me, the epitome of this kind of man was the poet Frank Stanford.

I met Frank sometime in the spring of 1978. I was twenty-five years old. I had been living in Houston and Austin, plying my trade in the music scenes, working odd jobs in restaurants and health-food stores to pay my bills, but I often went to Fayetteville to visit my father and stepmother, and sometimes I would stay there for weeks or months at a time. Dad was a poet who taught at the University of Arkansas, and he’d often host raucous literary parties. He’d break out his Southern-soul records—Wilson Pickett, Ray Charles. He loved Chet Baker and John Coltrane and Bessie Smith and Lightnin’ Hopkins. If the mood was right, I would get out my guitar and play songs.

Frank had studied poetry at the university, but I don’t think he finished his degree. He was a legendary figure in Fayetteville’s literary scene, though he never quite made a name outside of town. When I met him, he was working as a land surveyor to make ends meet. A land surveyor who wrote poetry—my kind of man.

Frank was twenty-nine years old and married to a beautiful, smart woman named Ginny Crouch, who was a painter. He was also living, on the side, with another beautiful, smart woman, the poet Carolyn (C. D.) Wright. Carolyn helped with the publishing company he started in Fayetteville. It was a pretty weird situation, married to one and living with the other, but Frank had lived a weird life. He was born in 1948 in rural Richton, Mississippi, and was immediately put up for adoption. He grew up in Greenville, Mississippi; in Memphis; and then, in his teen years, in Subiaco, Arkansas, where he attended a Catholic high school on the grounds of an abbey. His adoptive father was an engineer who helped build the levees on the Mississippi River. As a kid, Frank spent time in the levee camps, living with his family for months at a time among Black laborers. Once an interviewer asked him what he learned by growing up with Black people. “How shitty white people were to them,” Frank said. The landscape and the culture of the rural South were in his blood, and they showed up in his poetry, which was suffused with a carnal sense of death, danger, and beauty. When I met him, he had just written an epic poem called “The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You.” Here are the opening lines:

tonight the gars on the trees are swords in the hands of knights

the stars are like twenty-seven dancing russians and the wind

is I am waving goodbye to the casket of my first mammy

well that black cadillac drove right up to your front door

and the chauffeur was death

he knocked on the screen he said come on woman let’s take a ride

he didn’t even give you time to spit he didn’t even let you

take the iron out of your hair

you said his fingernails was made out of water moccasin bones

and his teeth was hollow he was a eggsucker

you said he reached up under your dress and got the nation sack

you said the conjure didn’t work he didn’t smell the salt in your shoes

you said he came looking for you hid out in the out house you waited

for him with a butcher knife you asked him why not

let the good times roll

That’s not even the first page, and there were three hundred and eighty-two more, without a punctuation mark in sight. His writing was feral and on fire. Everybody locally was proclaiming him the next great American poet. He knew a lot about blues and country music, and I think his poetry reflected that, but there was a bit of Flannery O’Connor in him, too, the imprint of the Southern-gothic tradition.

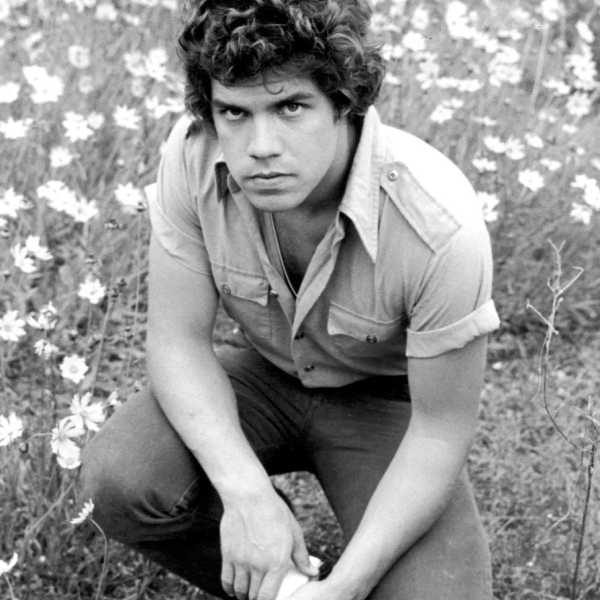

I found him irresistible, and so did a lot of other women and men. He was a cross between Jack Kerouac and a country boy. He was stocky, very fit, built like a wrestler or a rodeo man. He was charismatic, enigmatic, swashbuckling, sensitive. But there was also a part of him that was troubled, unstable. He was married to another woman before Ginny, and I was told that he spent some time in a mental hospital after that divorce.

I was in love with him. I don’t know what you would call our relationship. I wouldn’t say it was a love triangle, or a love square, with me and Ginny and Carolyn, because Frank and I never had sex. We just hung out and talked. He was genuinely attentive to what I said and he knew exactly what to say in response. He knew what I wanted to hear, which implies some sort of manipulation, but it also suggests to me that he cared. We talked about poetry and lyrics and desire, about caring for individuals and for the world, about how the world was so hard on most people, and about why it was important to be a poet or a singer even if your audience was never going to be very big. At the time, that certainly seemed to be the case for me.

Frank Stanford was a legendary figure in the Fayetteville, Arkansas, literary scene.Photograph by Ginny C. Stanford / Courtesy Poets.org

My relationship with Frank lasted only about two months. Three weeks after I signed my first record contract, on June 3, 1978, he killed himself by shooting a handgun into his chest. There are various accounts of the event, but here’s how I understand it. Frank had left town for a couple of weeks—possibly to go to New Orleans, to visit with the poet Ellen Gilchrist, whom he was close to. He was always leaving town on what he said were land-surveyor jobs, but Ginny and Carolyn found out that he was having affairs all over the region. When he returned from this particular trip, he found them waiting for him. They told him that they were on to his game, and that he had to choose one of them and stick with her, or that they would both leave him. Then he got a pistol from his office, walked into the bedroom, and shot himself. The whole thing resembled a Shakespearean tragedy.

Frank had sent flowers to my father’s house, and they arrived on the day he killed himself. I don’t know if he sent them on the same day or the day before or what. I got the flowers but I never saw him alive again. He had sent the flowers to let me know that he’d been thinking about me while he was gone.

My father was one of the first people Ginny and Carolyn called. They asked if he could come over and help clean up the bloody mess. My song “Pineola” pretty much tells the rest of the story, at least from my point of view. It was released in 1992, fourteen years after Frank’s death. Sometimes it takes that long to get a song right.

When Daddy told me what happened

I couldn’t believe what he just said

Sonny shot himself with a .44

And they found him lyin’ on his bed

I could not speak a single word

No tears streamed down my face

I just sat there on the living room couch

Starin’ off into space

Mama and Daddy went over to the house

To see what had to be done

They took the sheets off of the bed

And they went to call someone

Some of us gathered at a friend’s house

To help each other ease the pain

I just sat alone in a corner chair

I couldn’t say much of anything

We drove on out to the country

His friends all stood around

Subiaco Cemetery

That’s where we lay him down

I saw his mama, she was standin’ there

His sister, she was there too

I saw them look at us standin’ around the grave

And not a soul they knew

Born and raised in Pineola

His mama believed in the Pentecost

She got the preacher to say some words

So his soul wouldn’t be lost

Some of us, we stood in silence

Some bowed their heads and prayed

I think I must’ve picked up a handful of dust

And let it fall over his grave

I fictionalized a few details, but it’s all pretty much true. In the Catholic Church, if you killed yourself, you were screwed. You were going to Hell, and you wouldn’t be given a funeral. Frank’s mother was distraught, and she insisted that he have a funeral and be buried by the Subiaco Abbey. The Catholic diocese finally gave in. It was hard to include all that in “Pineola,” so I changed Catholic to Pentecostal. I preferred the sound of that word.

Two different worlds of people came together at Frank’s grave. There was a big turnout of his friends and followers; his family didn’t know any of them, and vice versa. I did pick up some dirt and toss it on the grave. It was a Southern-gothic story. A girl standing there with her little secret. There I was, and of course Ginny was there and Carolyn was there and Frank’s mother and sister were there, and I was the only one who knew anything about how I felt about Frank. Later I heard that Ginny and Carolyn moved in with each other for a while after Frank’s death. Another gothic twist to the story.

After my song came out, the legend of Frank Stanford continued to grow. His books were published in new editions. People started researching him and his work. Some people have told me that my song spurred this revival, but I’m not sure about that. One time, probably thirty or thirty-five years after Frank died, a writer called me and told me that he’d been digging into Frank’s papers at Yale, and that my name appeared in them. He told me that Frank wrote, “I feel free. I’ve been hanging out with Lucinda and she makes me feel freer.” That made me feel good, but it was also a bit unsettling. The writer intimated that Frank and I had had a tumultuous affair, which wasn’t true.

Frank’s suicide came four years after the suicide of another poet-friend, whom I had met at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, in Vermont. Over the years, my feelings about those deaths formed the basis of my song “Sweet Old World,” which was also the title of the album that included “Pineola.” “See what you lost when you left / This world, this sweet old world,” the chorus goes. “The breath from your own lips, the touch of fingertips.”

There was an obituary of Frank in the free weekly paper in Fayetteville. Alongside it was a poem that Frank had published, called “The Light the Dead See.” I clipped it out, put it in my scrapbook, and still have it today.

There are many people who come back

After the doctor has smoothed the sheet

Around their body

And left the room to make his call.

They die but they live.

They are called the dead who lived through their deaths,

And among my people

They are considered wise and honest. ♦

This is drawn from “Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You: A Memoir.”

Sourse: newyorker.com