“The King” is a stirring new documentary that addresses Elvis Presley’s complex cultural legacy and how it figures into our readings of the American Dream—it’s a movie about frontiers, and what it means to charge toward one. It chiefly stars Presley’s 1963 Rolls-Royce Phantom, which he had painted silver (it was originally a deep, midnight blue) after his mother’s chickens wouldn’t stop pecking at it. The film’s producers, and its writer and director, Eugene Jarecki, bought the car in 2014, when it went up for auction. They decided the best use of their bounty would be to drive it all the way across America, picking up or otherwise engaging a handful of celebrities (including Alec Baldwin, Ethan Hawke, David Simon, Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash, Van Jones, James Carville, and Chuck D) along the way. Some of them recorded songs in the backseat, some of them shared their memories of Presley, and some of them eagerly scoured the compartments for a stiff drink. (Jarecki told Variety that the Phantom broke down “about two dozen times” in the year he spent at the wheel.) “The King” is shot in widescreen CinemaScope format, a nod to both the hugeness of the American landscape and the hugeness of Presley’s ride. It’s glorious to watch the Phantom inch by, gleaming in the late-day sun, cresting each horizon like some stately but slow-moving spacecraft.

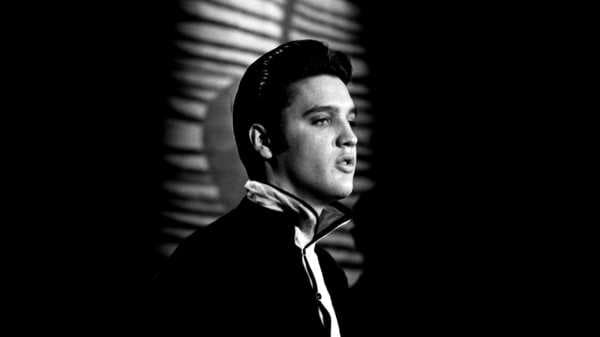

The conceit of “The King” is powerful in part because the idea of the road trip is so ingrained in the American sensibility, and in part because Presley himself is such an easy metaphor for what we hope America is, or can be: a place where miraculous things are possible. Presley was born in 1935 in Tupelo, Mississippi, about a hundred miles southeast of Memphis. He grew up poor, in a shotgun shack that his father, Vernon, built himself, after borrowing a hundred and eighty dollars to purchase the materials. Vernon failed to repay the loan, and, when Presley was three, the house was repossessed. The family eventually moved into a public-housing complex in Memphis. Jarecki and his team interviewed some of his old neighbors: “He was just like one of us,” the gospel singer Earlis Taylor says, before climbing into the back seat and singing a bit of a hymn. Part of Presley’s persistent deification has to do with the ways in which he embodies a very specific and intoxicating American myth: from very little, more.

In 1953, Presley wandered into Sun Records, a local recording studio, to make a two-sided acetate record as a gift for his mother. The studio’s owner and engineer, Sam Phillips, invited Presley back to record some demos. His first single, a cover of Arthur Crudup’s “That’s All Right,” was a local hit. By 1955, he had signed to RCA, and, the following year, “Heartbreak Hotel” went to No. 1.

“Heartbreak Hotel” was written for Presley by Tommy Durden and Mae Boren Axton. “If your baby leaves you, and you’ve got a tale to tell / Just take a walk down Lonely Street to Heartbreak Hotel,” the lyrics go. For years, the pair insisted its narrative was inspired by a Miami Herald story about a man who leaped out a window of the Atlantic Towers Hotel, leaving a one-line suicide note: “I walk a lonely street.” (Researchers have since come to believe that the tale is apocryphal.) The song is an eight-bar blues, loaded with reverb. Each time I revisit it, I’m surprised anew by its sparseness. The opening guitar and piano chords—slammed out, on the original recording, by Chet Atkins and Floyd Cramer—are a red herring. What follows isn’t rollicking but merely grim: “I feel so lonely I could die,” Presley mumbles.

Presley eventually sold around a hundred and thirty-six million records in the United States alone. His success came early enough in the history of the recording industry that there weren’t any precedents for eminence on this scale. Imagine being handed all that money, with no viable model for how to live or what to do with it.

In 1957, when Presley was twenty-two, he bought an eight-bedroom Colonial Revival house, on a stretch of thirteen acres of farmland in southern Memphis, for $102,500. Stephen C. Toof, a local businessman, had purchased the land in the mid-nineteenth century, and named it after his daughter, Grace. In 1939, his great-niece Ruth Brown Moore built a ten-thousand-square-foot mansion there with her husband, Dr. Thomas Moore, a professor of urology at the University of Tennessee.

Presley quickly spent half a million dollars customizing the place. He added a kidney-shaped swimming pool, a racquetball court, a meditation garden, and a wrought-iron front gate, painted white and fashioned to resemble an open book of sheet music; he had the grounds encircled with a wall of pink Alabama fieldstone. In the nineteen-seventies, a back porch on the first floor was converted into a recreation room, now known as the Jungle Room. He selected avocado-green shag carpet—it also lines the ceiling—and furniture that hews to a vaguely Polynesian theme. There are crystal liquor decanters, plastic ferns strung up in macramé hangers, and more ashtrays than seems reasonable. Critics dismissed Presley as vulgar and tawdry for much of his early career, and Graceland’s lurid interior feels, in a way, like a brash self-actualization—part of Graceland’s charm is in how it materializes a young man’s lavish, florid fantasy of wealth.

Much like the makers of “The King,” I recently found myself turning to Presley with hopes of understanding something about the state of my country: what it’s been through, where it’s going. Now a museum, Graceland receives around five hundred and sixty thousand visitors each year, more than any other home in America except the White House. I signed up for the Ultimate V.I.P. Tour, which costs a hundred and fifty-nine dollars, includes your own personal guide, and takes around three or four hours, depending on how long you linger over lunch at Vernon’s Smokehouse. (Visitors who purchase regular tickets are handed an iPad, which comes loaded with an audio tour narrated by John Stamos.)

Graceland has always been a fiercely domestic space. The morning of my visit, indentations in the plush living-room carpet suggested that it had been recently vacuumed. Hundreds of Presley’s personal effects are on display: his black leather wallet, his house keys, his Christmas decorations, his toaster, the gold I.D. bracelet that his daughter Lisa Marie wore as a baby. Across the street from the mansion, near Gladys’ Diner, a restaurant named after Presley’s mother, an exhibit called “The Archive Experience” features even more of Presley’s stuff. If you are a person who believes that artifacts have meaning—that objects tell stories, too—“The Archive Experience” is a kind of hysterical bonanza. Presley’s possessions are laid out for perusal, often with little or no context. Some are, nonetheless, thrilling to see—for instance, the twenty-five-inch RCA television Presley mysteriously shot a hole in after watching a Robert Goulet performance. “There was nothing Elvis had against Robert Goulet,” a spokesperson told the Associated Press, in 2006. “They were friends. But Elvis just shot out things on a random basis.”

By the early nineteen-seventies, Presley was addicted to opiates, particularly the pain medication Demerol, which was meted out to him by his personal physician, George C. Nichopoulos. On two separate occasions, in 1973, Presley overdosed on barbiturates. He died in 1977, at Graceland, of heart failure. His fiancée, Ginger Alden, found him unresponsive in an upstairs bathroom. It was an undignified way to go.

Graceland opened to the public on June 7th, 1982, and has since received more than twenty million guests. Some estates are more opulent (like Hearst Castle, in San Simeon, California), and some are comparably retro and domestic (like the Louis Armstrong House, in Corona, Queens). Twin Palms, Frank Sinatra’s Palm Springs hideaway, is available to rent for weddings and private events; Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s compound outside Charlottesville, Virginia, opened to visitors in 1954. But there is an unmistakable lure to Graceland as a site of pilgrimage. It’s now a piece of beloved national kitsch, essential for any cross-country road trip, and meaningful not only for its evocation of Presley’s life and work but for the sea change he and his work represent: the conservative, segregated nineteen-fifties giving way to a different kind of decade.

In 1986, Paul Simon named an album after the estate. “For reasons I cannot explain, there’s some part of me that wants to see Graceland,” he sings on the title track. “Maybe I’ve a reason to believe we all will be received in Graceland.” In a 2014 video produced by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Simon positions the trip as a spiritual voyage: “Being in the crowds that come to Graceland, it’s almost like a religious thing about Elvis,” he explained. “It eventually became about this journey, this father-and-son journey, to mend a broken heart. Graceland became more like a metaphor than an actual destination.”

Visitors to Graceland are “received” in the old-fashioned sense—they are politely and warmly welcomed—but Simon’s lyric has theological undercurrents, too. It suggests a kind of heaven: a place a person might go to achieve universal salvation, to be disburdened of her sins and returned to eternity. Simon is drawn there with the idea of starting over. It seems worth pointing out that Graceland itself is overloaded with icons: portraits, sculptures, abstract depictions. At the foot of the driveway, there is a literal pearly gate. Each August, on the anniversary of Presley’s death, fans from all over the world deliver immortelles—durable floral arrangements, fashioned from artificial blooms and plastic ornaments—to his graveside. For an hour every morning, before the mansion opens for tours, visitors may call on the grave for free. To this day, there are still reports of resurrection. Elvis, alive, seated at a Burger King in Kalamazoo, Michigan, scarfing Whoppers. Elvis pumping gas, somewhere outside of Las Vegas.

About a decade ago, on my first trip to Graceland, I spent a couple of nights at Elvis Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel, which was built, adjacent to the mansion, in 1989, and featured a hundred and twenty-eight guest rooms (it has since been torn down and replaced by a bigger, more opulent hotel). Back then, it was a bastion of lonesome camp. There was a heart-shaped pool in the back, with a line of black tiles jutting across the bottom, indicating fracture. The bar was thickly carpeted, and crowded both early and late. It was an endlessly enticing destination for anyone looking to make his or her descent into romantic devastation more literal. I knew, even then, that it would be a place I’d return to at different points in my life—in seasons of joy, or sadness, or confusion.

People often travel to Graceland when they’re looking for something, or when they want to feel closer to a shared history. Joel Weinshanker, the C.E.O. of Graceland Holdings, the company that operates Graceland, first visited the property in the nineteen-eighties, when he was managing a heavy-metal band called Trixter. He recently told me that he was overwhelmed by the “gravitas” of the home—the hugeness of Presley’s life and work. “At that moment, I said to myself, ‘I’m going to be involved with this some way, I just don’t know how.’ ” In 1996, Weinshanker founded a company that manufactures toys and collectibles, and, when Graceland went to auction, he bid on a controlling interest. “Everyone looked at Graceland as this old, tired property, except for me,” he said.

It’s a challenge to square Graceland’s enduring popularity with Presley’s present standing in the culture. Though his vocal and performance style is ingrained in contemporary pop (in 2015, Spotify launched a tool called the Elvis Influence, in which users can type the name of almost any artist into a search bar and discover how or if they’re connected, musically, to Presley—and almost every artist you can think of is, in one way or another), there are indications that his relevance as a primary source for younger artists is ebbing. Presley’s earliest influences (Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Rufus Thomas, Arthur Crudup, Jimmie Rodgers, the Grand Ole Opry) were a reflection of the gospel music he heard at his Pentecostal Assembly of God church, the blues singers he saw at small clubs on Beale Street, and the country music broadcast on the radio. Presley borrowed elements of all three—which is to say that he learned from less acknowledged and infinitely less compensated black performers. This has been a point of moderate controversy for decades. Younger listeners, who came of age with the phrase “cultural appropriation” close at hand, are perhaps even more awake to issues of insidious creative pilfering, particularly across racial or ethnic lines.

Presley’s insistence on integration, which often meant showing up at “blacks-only” events in Memphis, made him a kind of imperfect idealist—his biographer Peter Guralnick refers to his world view as “a democratic vision.” In an Op-Ed in the Times, from 2007, Guralnick suggests that Presley’s guilelessness was genuine, and perhaps born of his upbringing: “He was simply seen as too low class, or perhaps just too no-class, in his refusal to deny recognition to a segment of society that had been rendered invisible by the cultural mainstream,” he wrote. The Memphis World and the Tri-State Defender, the two black newspapers in Memphis at the time, both reported favorably on Presley, whom they saw as a kind of ally.

But it’s largely impossible to pay out royalties on influence, and the economic disparity between the artists Presley learned from and the colossal wealth he accrued in his lifetime has only further problematized his legacy. “You talk about the American dream—Elvis Presley was born into an American nightmare,” Van Jones says in “The King.” “It’s an interesting country. It inflicts pain on black people, denies that it inflicted pain, but then benefits from the soulful cry that arises from the pain.” In Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” from 1990, Chuck D puts it a different way: “Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant shit to me you see / Straight up racist that sucker was / Simple and plain / Motherfuck him and John Wayne.” In an interview for “The King,” Chuck D stands by the sentiment. “He was called the King of Rock and Roll, which I took offense to, because he was no more of a king than Little Richard. He was no more of a king than Bo Diddley.”

In 2016, Presley was streamed three hundred and eighty-two million times on Spotify. Compared to a band like the Beatles (1.3 billion streams), who débuted eight years after him, that figure feels low. Nevertheless, thirty-two per cent of Graceland’s visitors are younger than thirty-five. The site’s appeal is not exclusively musical. Somehow, Presley’s arc—a young man born with little invents something new, makes it big, bejewels dozens of jumpsuits, stays loyal to his noncoastal birthplace, and is ultimately undone by his excesses—remains significant to people. It means something.

On my most recent visit, I was struck by the diversity of the crowd—older couples still in their church clothes, whole families tumbling out of bug-flecked Sprinter vans, giggling twenty-somethings, and plenty of lone and searching pilgrims, like me. Graceland tells a story about what America can be, and how those ideals can go wrong. The artist William Eggleston, who photographed Graceland in the nineteen-eighties, once told me that he found the whole place grotesque. He’s right—it is grotesque, and gorgeous, and ours. A vision of America, waiting for us, in Memphis.

Sourse: newyorker.com