Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

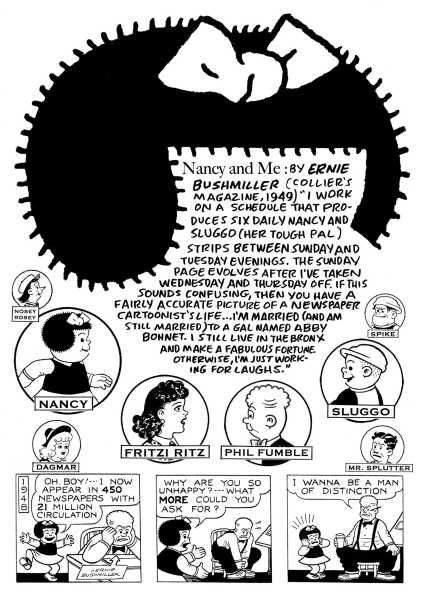

There are movies about filmmaking, and novels about professors of literature, but there aren’t many comic-book biographies of cartoonists. Enter Bill Griffith, who, as the creator of a character called Zippy the Pinhead, is one of the very few contemporary cartoonists who has managed to keep a daily strip going for decades, starting in 1970. The subject of Griffith’s forthcoming biography is spelled out in the title: “Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller, the Man Who Created Nancy.” Bushmiller was the creator of one of America’s most ubiquitous cartoon characters. In 1933, he introduced an eight-year-old kid, Nancy, to his widely popular strip “Fritzi Ritz,” about a bombshell flapper living in New York City. Round-faced, with dots for eyes and a baby-doll silhouette, Nancy captured the public’s attention thanks to her bright ideas, unwavering aplomb, and penchant for finding trouble even in the most ordinary of circumstances. As the fellow-cartoonist Wally Wood apparently once quipped, it’s harder to not read “Nancy” than to read it.

For modern-day cartoonists, Bushmiller’s “Nancy” has long represented the essence of the distillation inherent in comics. As Scott McCloud related in “Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art,” “Art Spiegelman explains how a drawing of three rocks in a background scene was Ernie’s way of showing us there were some rocks in the background. It was always three. Why? Because two rocks wouldn’t be ‘some rocks.’ Two rocks would be a pair of rocks. And four rocks was unacceptable because four rocks would indicate ‘some rocks’ but it would be one rock more than was necessary to convey the idea of ‘some rocks.’ ”

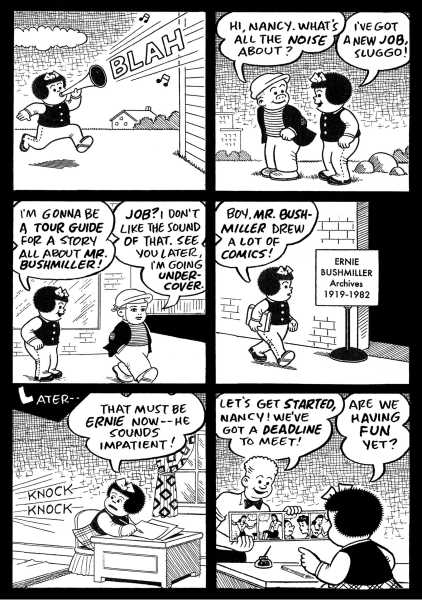

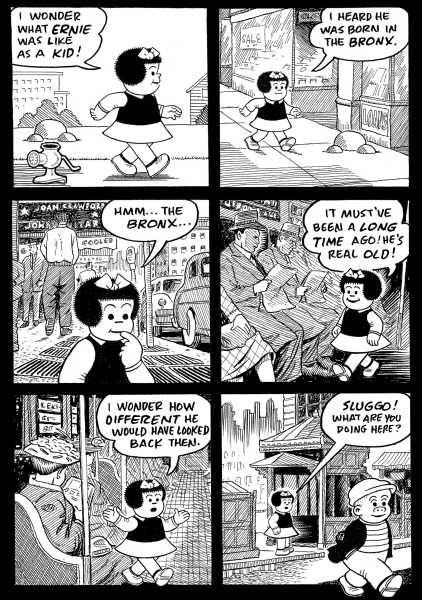

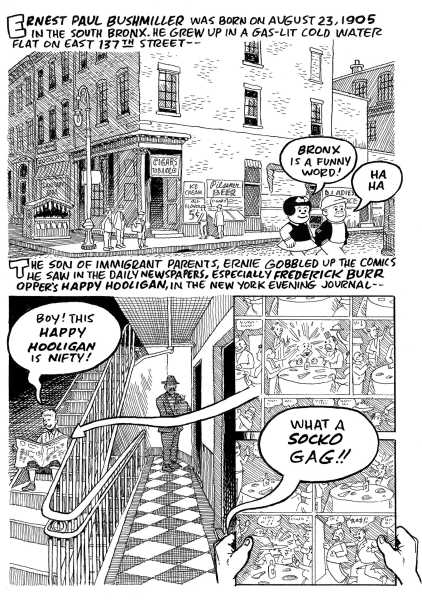

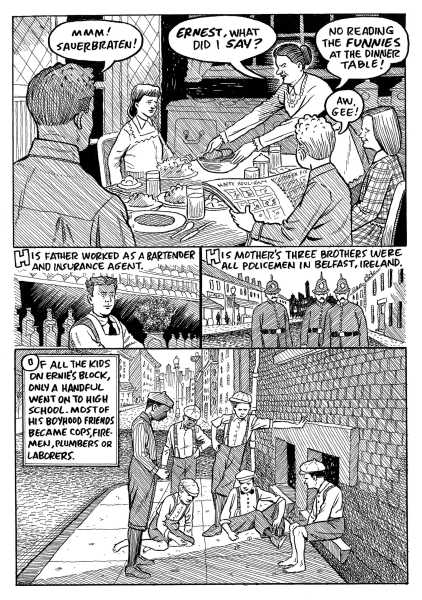

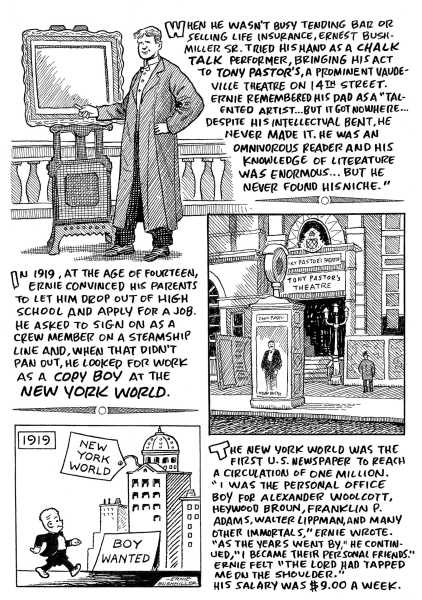

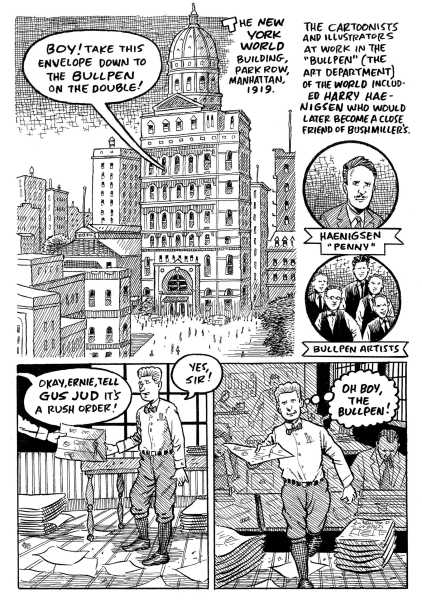

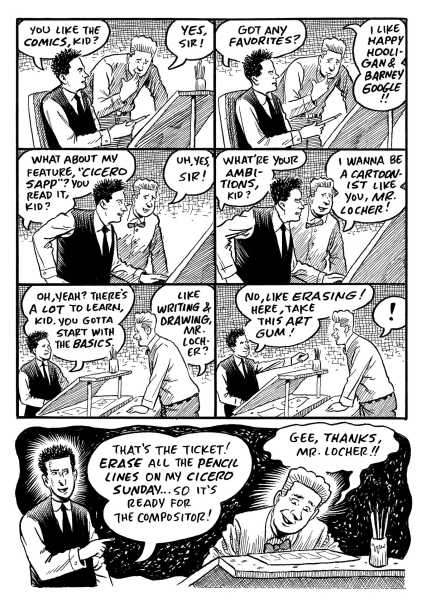

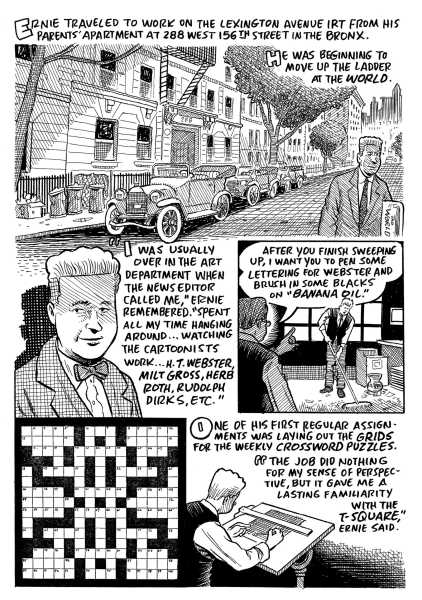

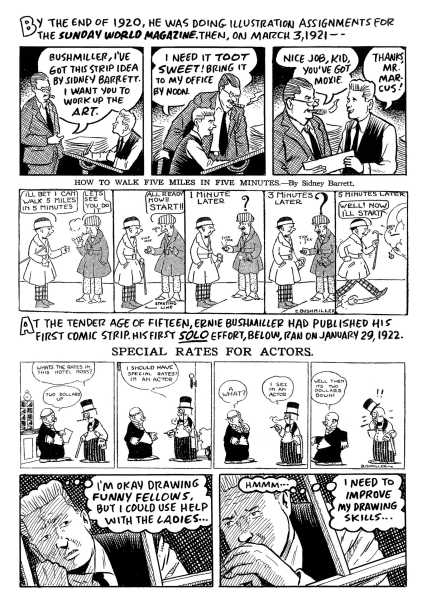

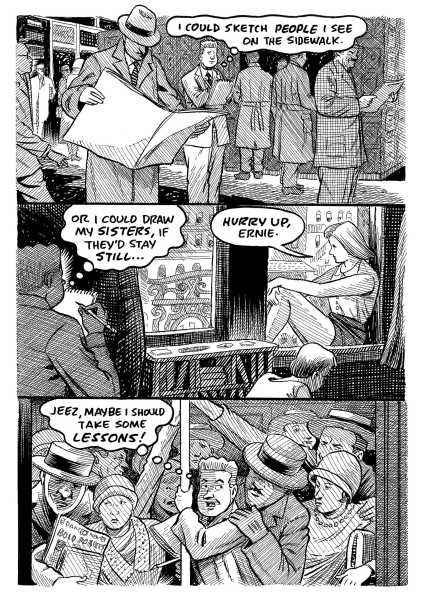

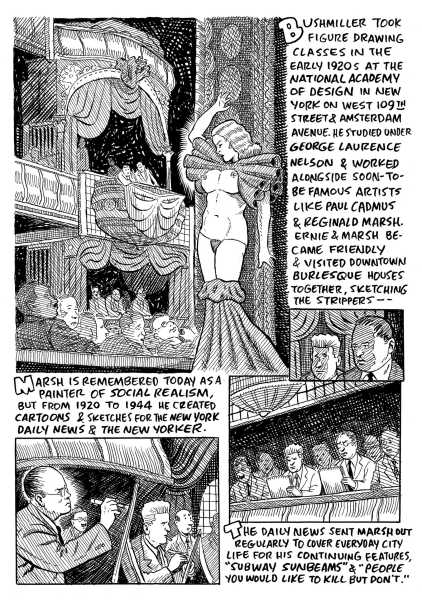

Griffith follows Bushmiller, a Bronx native born to immigrants in 1905, through his transformation from a teen-age copy boy to a successful cartoonist whose beloved characters engendered their own world. (Would Nancy be Nancy without Sluggo, her best friend and co-conspirator?) Griffith draws Bushmiller’s life in the language of “Nancy”: in clean lines, equal-size panels, and short bursts of dialogue, painting a portrait of a superstar cartoonist during an era of syndicated comics and widespread readership when virtually everyone, young and old, read the paper.

There’s a bygone glamour to Griffith’s rendition of Bushmiller’s New York, replete with crowded cartoonists’ dens, couriers dashing off to get the daily strip to press, and long, smoke-filled lunches with fellow-cartoonists, including Bushmiller’s close friend Milt Gross. But Griffith does more than evoke an era; he asks questions about Bushmiller’s artistic motivations, pondering Bushmiller’s love of surrealism and his habit of sneaking inexplicable moments into Nancy’s otherwise pedestrian world. “Nancy,” the strip, sometimes reads like a puzzle, not unlike her creator: a conservative-leaning workaholic who maintained a correspondence with Samuel Beckett; an absurdist who strove, daily, with meditative devotion, to get the gag down in the fewest strokes possible. We spoke to Griffith about what led him to want to inhabit another cartoonist’s style and skin.

When did you first encounter Nancy? Were you always a fan?

My first exposure to Nancy was in the funny pages of the Sunday newspaper delivered to my house in Brooklyn in the late nineteen-forties. I remember feeling drawn not to the art or the humor of the strips but to its lettering. Since I was just learning to read, “Nancy” seemed user-friendly. The letters were nice and big, with plenty of inviting airspace inside the word balloons, with a minimum of punctuation to decipher. So “Nancy” was imprinted on me at this time, and that feeling stayed with me, even as I got older and began to develop more adult tastes in comics, like “Pogo” or “Plastic Man.” It’s only later that I realized the zen quality of the strip. In one of Nancy’s earliest appearances, from 1933, she sits on her lawn atop three rocks. Not one rock. Not two rocks. Three rocks. They invite meditation. They ask that you pause and take in their perfect hemispheres—their “three rocks”-ness.

What, if any, misconceptions did you have about Bushmiller before writing this book? What were you surprised to learn?

Before I started to research “Three Rocks,” I will confess to assuming that Ernie Bushmiller was a man of average intelligence, with a conventional level of sophistication. I figured he was probably unaware of, or uninterested in, the larger world of art and comics. I was quickly disabused of this notion once I began to have lengthy talks with Ernie’s former “right-hand man” and neighbor, Jim Carlsson, still alive and well and living just a few hours from me, in Connecticut. Jim recounted conversations he had with Ernie about Diego Velázquez and Fats Waller. I even learned that Ernie had an appreciation for Robert Crumb’s early “Zap” comics, though more for the craft than the content.

In telling the life of another cartoonist, did you learn anything about your own practice of the medium?

The life of a daily cartoonist is a little like that of a monk in his cell. Having to produce one strip every day, day in and day out, with no time off, made me feel a kinship with Bushmiller, especially as I got deep into the book. On the other hand, unlike him, I don’t do four strips at a time on four different drawing tables in my studio, and I’ve never used assistants. Ernie said that he didn’t let the outside world into “Nancy,” but, in reading his work thoroughly, I noticed occasional cameos by Fidel Castro, Nikita Khrushchev, and several unkempt beatniks and hippies. I usher in the real world almost every day in my “Zippy” strip. So, yes, we are both satirists.

Though Nancy never grows up, Bushmiller adapted her to every decade. Could you conceive of a Nancy who is relevant in 2023?

Actually, there is an updated version of Nancy out there, and it has its fans. The strip bears almost no relation to Bushmiller’s Nancy and Sluggo, but, since the “Nancy” strip was originally copyrighted in the syndicate’s name, they can do what they want with it, in perpetuity. I will resist making a judgment as to that decision.

So the answer is no—Nancy has no need to be relevant to 2023. She shall, however, live forever in Bushmiller’s world, where she walks calmly across one manicured lawn, passes one tree, one fence, and leaves behind, for all of us to contemplate, three rocks.

In the excerpt below, Ernie gets his first job at a newspaper and strives to improve his figure-drawing skills.

This is drawn from “Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller, the Man Who Created Nancy.”

Sourse: newyorker.com