“History Keeps Me Awake at Night,” the Whitney Museum’s retrospective of the works of the artist, writer, and activist David Wojnarowicz, opens with a mask of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Wojnarowicz made the mask out of cardstock and a rubber band, using a famous photograph of the poet at the age of seventeen, and then took a series of photos of his friends wearing it around New York City in the late seventies. Rimbaud rides a densely graffitied subway train; Rimbaud tries to cross an avenue in rush-hour traffic; Rimbaud lies naked on a bed with his penis in one hand; Rimbaud poses with a syringe in his left arm, a bandanna used for a tourniquet. Wojnarowicz, whose artistic career spanned the late seventies to his death, from AIDS, in 1992, at thirty-seven, posed the Rimbaud portraits in spots around New York that were significant in his own life, primarily the places where he had hustled as a child prostitute in his teen years.

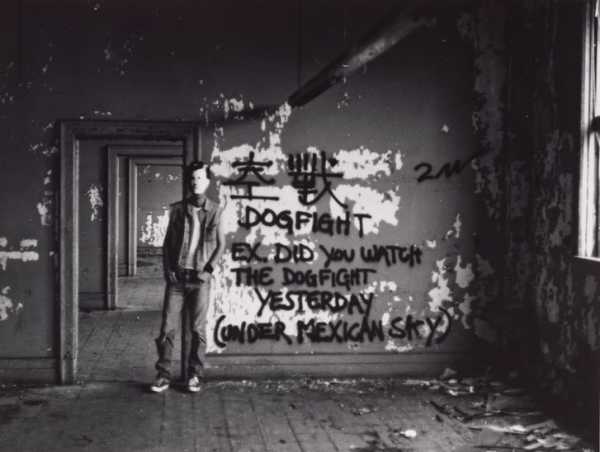

Wojnarowicz identified with Rimbaud when he took those photos, and in the twenty-six years since his death, he has became a Rimbaud-like figure: young, iconoclastic, gay, and gone too soon. In his early career, he stencilled graffiti on the abandoned buildings of the bankrupt city, scrawled poetry on the dirty walls of the Chelsea Piers, where he went to cruise for anonymous sex, and wrote moving essays and diary entries that described the beauty he found in the parts of his life that made him an outcast: being gay, and being addicted to heroin.

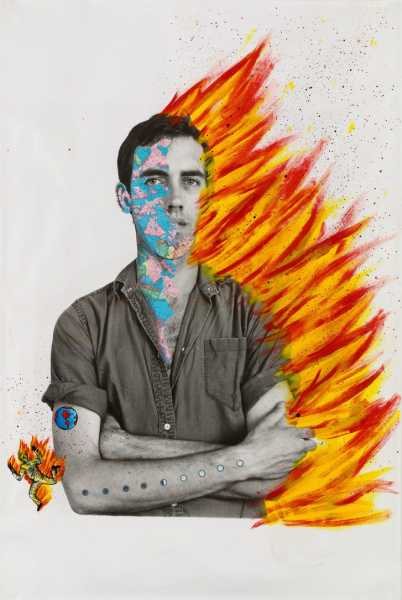

“Self-Portrait of David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992),” 1983–84.

Photograph by David Wojnarowicz and Tom Warren

What we know of Wojnarowicz’s youth suggests that it was brutally painful. Holland Cotter, writing in the Times, says that the artist’s account of his own early life was “romantically massaged but based in fact.” What seems certain is that his parents abandoned him sometime shortly after their divorce, when he was two, leaving him to drift among a series of temporary homes, some of them abusive. He started turning tricks in his teens, and was injecting heroin soon after. His earliest work consists of paintings done on supermarket posters, stencils made of cardboard—materials that he could forage or steal.

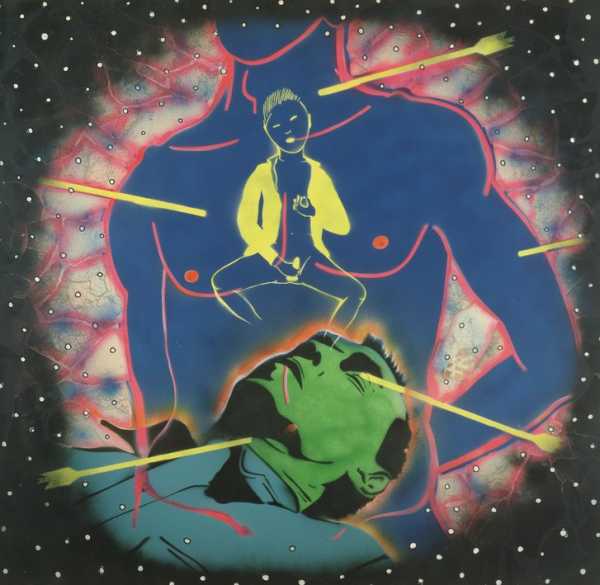

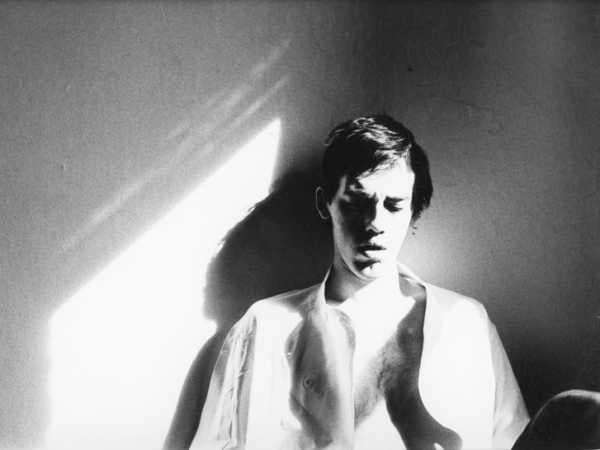

”Peter Hujar Dreaming/Yukio Mishima: St. Sebastian,” 1982.

New York was a different city then, more dangerous and less glamorous but also much cheaper, and in some ways more welcoming to the artistically ambitious. Through his art and his busboy job at the downtown dance club Danceteria, Wojnarowicz met established artists who became his professional champions; Nan Goldin, Zoe Leonard, Paul Thek, Luis Frangella, and Kiki Smith all became his good friends and helped him parlay his graffiti work into shows at downtown galleries. A place in a 1985 Whitney show followed. But Wojnarowicz’s art did not develop power and pointedness until 1987, when his close friend, the portrait photographer Peter Hujar, died, of AIDS, in St. Vincent’s Hospital, in Greenwich Village.

“Arthur Rimbaud in New York,” 1978-1979.

Twenty years Wojnarowicz’s senior, Hujar had been a lover, a teacher, and a father figure. It was Hujar who had first taken Wojnarowicz’s art seriously, Hujar who first encouraged him to try painting, Hujar who gave Wojnarowicz a place to stay, at his loft on Second Avenue, Hujar who chided him to give up heroin. The AIDS crisis was raging by then, and the gay community and downtown arts scene alike were being brutalized by the disease. Hujar died slowly, wasting away in the loft that he and Wojnarowicz had shared. In his diaries, Wojnarowicz describes Hujar’s long illness and desperate attempts to cure himself. In one episode, Wojnarowicz writes that he accompanied Hujar to a clinic on Long Island, where they discover that a quack doctor is injecting AIDS patients with human feces.

”Untitled,” 1987.

Wojnarowicz never recovered from the loss of Hujar; it would fill his art with defiance and moral outrage for the rest of his life. In one gallery, three black-and-white portraits of Hujar’s body are mounted side by side, showing his face, hands, and feet. Wojnarowicz took the pictures moments after his friend died. Hujar had been handsome, with a strong chin, broad forehead, and sharp eyes. In the picture taken after his death, he is unrecognizable. He is so thin that his collarbone protrudes from the hospital gown like a drawer pull; his eyes are sunken and half open. It doesn’t look like he’s sleeping or in repose. It looks like he’s in pain.

”Untitled,” 1987.

“Untitled,” 1987.

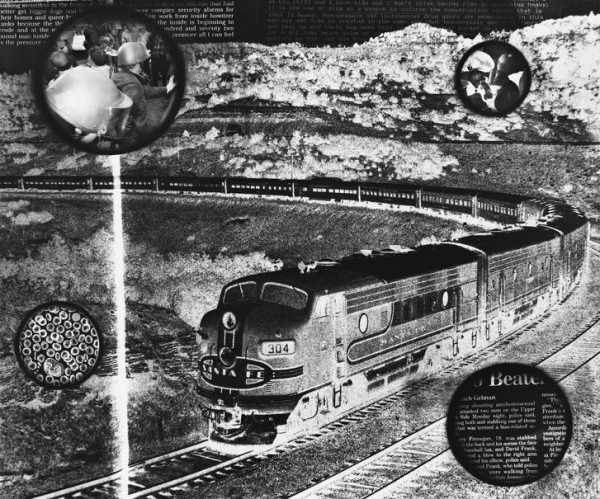

Wojnarowicz received his own H.I.V. diagnosis in the spring of 1988, just a few months after Hujar died. The art that he made in the following years was furiously political. As the AIDS crisis burned on, he moved away from painting and focussed more on photography, collages, and writing. In one collage, a long locomotive winds through a vast American desert. That image is surrounded by inset circles where police in riot gear surge into a crowd, a distorted still from a porno shows a man performing oral sex, and an article details the stabbing of a nineteen-year-old gay man. In another, an aerial shot shows soldiers parachuting out of military planes above an inset picture of two men on a bed, having sex.

“Untitled,” from the Sex Series (for Marion Scemama), 1989.

If the messaging of these works is not exactly subtle, neither were the politics of the AIDS crisis in the late eighties and early nineties. Wojnarowicz did not see the epidemic as a tragic accident of biology but as an act of willful, mendacious neglect by the American government. He had reason to feel this way. At the time, AIDS drugs were scarce, inconsistently effective, and expensive; most patients couldn’t get access to them. (The antiretroviral cocktail that would make H.I.V. survivable long-term was not introduced until 1996.) In the meantime, misinformation about how H.I.V. was contracted spread widely, and fear of the disease ignited vicious public homophobia. During the time that Wojnarowicz was making this art, Republican lawmakers were calling for homosexuals to be quarantined, branded, and even killed. Much of Wojnarowicz’s art from this period seems to be addressed directly to them, and its tone is combative, indicting, and angry. In one collage, Senator Jesse Helms is depicted as a poisonous spider, a swastika patterned on his back.

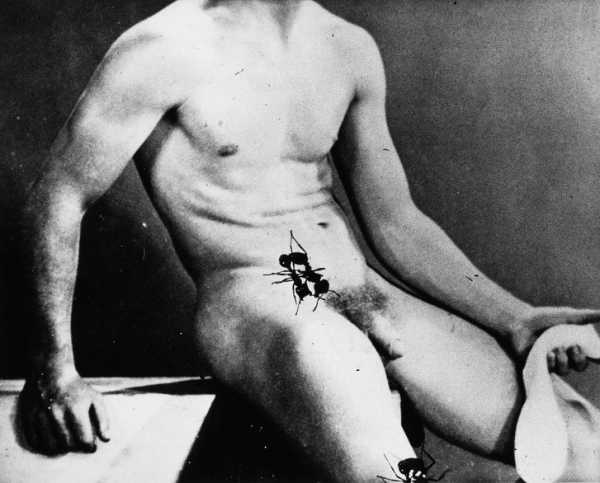

“Untitled” (Desire), from the Ant Series, 1988-1989.

”Untitled (Time and Money),” from the Ant Series, 1988-1989.

During Wojnarowicz’s lifetime, his work was cited by the religious right as an example of the sort of art that should be denied funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. After the American Family Association used his work in a pamphlet that decried federal funding for homosexual art, Wojnarowicz sued them, and he won. At the Whitney, a typed statement that Wojnarowicz submitted for that lawsuit appears in a glass case, annotated by hand in red pen. At one point, Wojnarowicz describes himself as H.I.V.-positive, but then crosses out that diagnosis, to insert “AIDS-symptomatic.” The controversy surrounding his work has not subsided since his death. As recently as 2010, the Catholic League, backed by Republican congressmen, objected to a part of a Wojnarowicz video that showed ants on a wooden crucifix. They led a successful campaign to censor his work from an exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery, in Washington, D.C.

”Something from Sleep II,” 1987-1988.

Because Wojnarowicz was so vivid and uncompromising in his moral outrage, and because his writing about the injustices, bigotries, and abuses of power that led to his own death is so searingly lucid, it can be uncomfortable to admit that some of his artwork is not very good. His paintings, in particular, can be disappointing, drawing heavy-handedly on Frida Kahlo magical realism and the pop-art sensibilities of artists such as Richard Hamilton and Keith Haring. It may be more accurate, and more fair, to judge him as a moral crusader, whose indictment of government indifference and hostility toward its most vulnerable groups resonates as urgently today as it did during his lifetime. There is a sense that he was working against time to depict the humanity of AIDS victims, to show the meaning of his own suffering to a country that didn’t seem to care. One of his most famous works, a photograph taken less than a year before he died, is called “Untitled (Face in Dirt).” In it, Wojnarowicz lies in a shallow grave, his face just barely emerging from the dry, crumbling earth.

“Iolo Carew,” 1980.

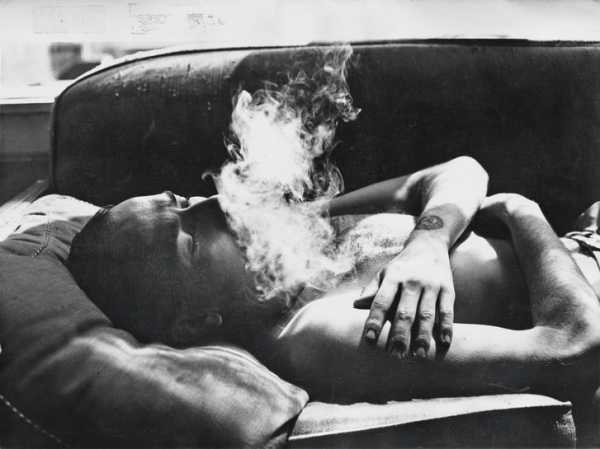

“History Keeps Me Awake At Night” arranges Wojnarowicz’s work chronologically, but on my recent visit I made a mistake, and went through the galleries backward. I took in Wojnarowicz’s later work first—the collages of photos with large blocks of angry, detailed text, the photos of Hujar’s dead body, the photo collages showing solar systems, men with guns, and pornography. I moved through his midcareer work, and the portraits the Peter Hujar took of him—shirtless, smoking, and smiling, they’re a rare image of the artist looking happy and at ease. I finished by looking at the art that Wojnarowicz made in the early eighties, which is joyful, playful, colorful, and imaginative. He worked in neons, with spray paint and found materials. A speaker mounted in a corner played the catchy, irreverent music that he recorded with his punk band, 3 Teens Kill 4. It was impossible, travelling in reverse through Wojnarowicz’s foreshortened career, not to think of all the life that was taken from him.

“Autoportrait—New York,” 1980.

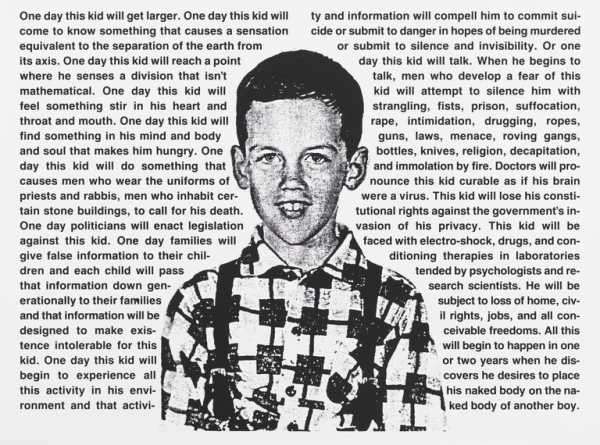

One of Wojnarowicz’s most famous works is the collage “Untitled (One day this kid . . .),” which features a childhood photo of Wojnarowicz superimposed against blocks of text. In the picture, the young Wojnarowicz is unmistakable: he has the same long forehead, the same pointed chin, the same gap between his front teeth. He is maybe nine. “One day this kid will get larger,” it reads. “One day this kid will do something that causes men who wear the uniforms of priests and rabbis, men who inhabit certain stone buildings, to call for his death. One day politicians will enact legislation against this kid. One day families will give false information to their children and each child will pass that information down generationally to their families and that information will be designed to make existence intolerable for this kid.” Then, later, something vital: “One day this kid will talk.”

“Untitled (One day this kid . . .),” 1990-91.

Sourse: newyorker.com