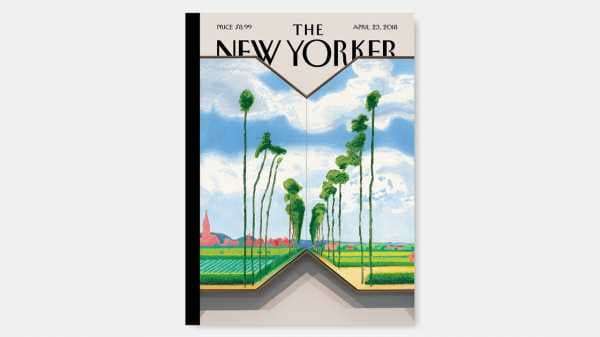

Cover for travel magazine and the results of food, “the road” with a new painting by David Hockney. Hockney, who last year celebrated his eightieth birthday with a retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum, still restless stylist. He spent several years drawing on an iPad—phase, which gave a handful of new Yorker covers and his later work plays with photography, collage, and hexagonal canvases.

His last cap fits “Tall Dutch trees after Hobbema (useful knowledge) 2017”, which is itself a riff on “the Avenue at Middelharnis,” seventeenth-century Dutch painter Meindert Hobbema. Hockney recently sat down to answer a few questions about coverage and his new job.

Hockney “Tall Dutch trees after Hobbema (useful knowledge),” currently on view at the pace gallery.

Photos Krista Schluter for new York

Meindert Hobbema in 1689 painting “Avenue at Middelharnis”, which is on exhibit at the National gallery.

Courtesy National Gallery, London

What draws you to painting Hobbema this?

I’ve always loved him. It’s a beautiful painting, original. It is in the National gallery, and I saw him when I was eighteen when I first came to London. I said JAP [companion Hockney]—just look up Hobbema. He had never heard of him, we found picture proof (it was pretty good!), and then I painted.

Van Gogh also wrote about work. What is striking is that in painting, there are two vanishing points. In the center of the picture, the vanishing road. And the other in the sky. You always look up, because the trees are so high.

This is an interesting dialogue with other work.

Well, I expanded it. Wider perspectives are needed now. I made a poster that says that in 1986.

How did you get into this idea of cutting out parts of the canvas?

I did the opposite point of view before, something like “Kerby (after Hogarth),” in 1975, I think. I call it “useful knowledge”. He only recently became useful, though.

Hockney outside the gallery pace.

Photos Krista Schluter for new York

The term occurs a lot in your work recently. What is reverse perspective?

If you go through the tunnel when you come out, all opens. This is reverse perspective. The problem with this standpoint: you’re a fixed point, here, outside the picture. But from the opposite point of view, you can be moving you can see all sides from one point. And we are always in motion. The eye is constantly in motion. He is never still. Cubism, for example, really was an attack in the future.

What made you go back to the technician in a perfect way?

I explained to JP last year, I was interested in a reverse perspective. Then I went to bed. Then he looked up “reverse perspective” on the Internet, and eventually found this eighty-page essay [Paul] Florensky, which he printed out and put on my chair. In the morning I read it. And I thought it was fantastic, absolutely fantastic.

When it was written?

In 1920-m to year.

At the height of Cubism.

Yes, exactly. [Florence] was a Russian monk, a scholar, a linguist—he was like the Leonardo. He was executed by Stalin in 1937. In the sixties, in Russia, they began to say, “well, he was shot by mistake,” and began to look at his work. But this essay gave me a lot of confidence. Like, Oh, Wow, I am in the trial.

Hockney between the two new works, “the Annunciation” and “second Annunciation.” The paintings belong to the triptych, in which Hockney began to experiment with hexagonal blade.

Photos Krista Schluter for new York

Are you still doing things on the iPad?

Not so much at the moment, I’m just painting away. When I worked on iPad, that’s all I do. It was 2010, 2011, 2012. Twenty-twelve or two thousand and twelve? I wrote for the new York times, in 1999, after thirteen hundred come thousand four hundred come fifteen hundred, etc … it must be twenty-one hundred! Why suddenly start counting in thousands? Someone noticed the numbers.

Read more about David Hockney, read:

A profile of Lawrence Weschler artist.

Andrea K. Scott, in retrospect.

For iPad Hockney cover.

Sourse: newyorker.com