David Crosby, one of the most iconic and enduring voices of the nineteen-sixties, died last week, at the age of eighty-one. He was a founding member of the Byrds and of Crosby, Stills, and Nash (sometimes Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young), two deeply beloved and influential folk-rock outfits. For anyone who found solace or haven in Crosby’s singing, his death feels like the dimming of some golden light.

Crosby was born in Los Angeles in 1941, and, by the late nineteen-sixties, he was a central figure in the art scene taking root in Laurel Canyon, a woodsy, bohemian enclave on the slopes of Lookout Mountain, in the West Hollywood Hills. At various times, Crosby’s Laurel Canyon cohort included Joni Mitchell (whom he consistently championed and very briefly dated), Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn, Linda Ronstadt, J. D. Souther, Judee Sill, Carole King, Frank Zappa, and members of the Mamas and the Papas and the Eagles. Back then, Laurel Canyon was a countercultural oasis in the midst of L.A.—imagine rustic cottages with wood-burning fireplaces and spider plants dripping out of hand-tossed pots, with plentiful weed and incense smoke drifting up from little brass holders, and all-night jam sessions—and Crosby, too, felt like an emissary for a different sort of American sound, more spectral, almost phosphorescent. His voice was sweet but vaguely spooky, as though it were emanating from the inner depths of a seashell you once held to your ear. As though it were not wholly of this world.

Crosby’s commercial career began in 1965, when the Byrds’s jangly, tenderhearted cover of Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” became a No. 1 single. Two years later, by Crosby’s own account, he was kicked out of the group after his bandmates accused him of being “terrible and crazy and unsociable and a bad writer and a terrible singer.” In 1968, he started playing with Stephen Stills, of Buffalo Springfield, and Graham Nash, of the Hollies. (In 1969, they added Neil Young to the lineup; he recorded with the band periodically until 2013.) There were lots of hits (“Our House,” “Southern Cross,” “Teach Your Children,” “Ohio,” “Just a Song Before I Go”) and lots of arguments, particularly as the decades stacked up. “When you meet, when you start a band, you’re in love with each other,” Crosby told Christiane Amanpour in 2019. “When you’ve done it for forty years, and it’s devolved to just, ‘Turn on the smoke machine and play your hits,’ it’s not musically exciting, it’s not fun, and we weren’t friends.”

In 1971, during a hiatus from the band, Crosby released a solo album, “If I Could Only Remember My Name,” which he wrote while living on the Mayan, his fifty-nine-foot mahogany sailboat, and grieving the sudden death of his girlfriend, Christine Hinton, who was killed in a car accident while driving the couple’s two cats to the veterinarian. Though the album was not widely celebrated at the time of its release (the critic Robert Christgau called it “disgraceful,” giving it a grade of D- in the Village Voice), the record was later sought out and heralded by fans of surreal, haunted, jazz-inflected folk rock, who found beauty and elegance in its gentle, psychedelic meanderings. On “I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here,” Crosby sounds as though he’s disintegrating spiritually, singing in a soft, echoing harmony with himself. It is one of the best and most affecting evocations of fresh grief I’ve ever heard.

In the eighties and nineties, Crosby suffered. He later cited Hinton’s death, and his inability to process it, as the thing that pushed him toward shooting heroin and freebasing cocaine. In 1982, he was arrested on drugs and weapons charges, and later spent months in a Texas state penitentiary. In 1984, he was arrested again, for drunk driving and driving with a suspended license. In 1994, he received a liver transplant with the help of his friend Phil Collins. There’s a funny, resonant moment in “David Crosby: Remember My Name,” a 2019 documentary about Crosby’s life and work, in which Cameron Crowe asks why Crosby is still alive. “No idea, man,” Crosby replies.

In an era in which likability (if not goodness) is heralded as a supreme virtue, the Croz remained irascible, short-tempered, and prone to unequivocal declarations, especially on Twitter, which he joined in 2011, and used enthusiastically until he died (he posted or retweeted more than a dozen times on Wednesday, the day before his sister-in-law, Patricia Dance, confirmed his death). Crosby embraced the odd grammar of Twitter—its randomness, its concision, its immediacy—and would often engage directly with strangers who provoked or petitioned him. He retweeted compliments. He made fun of Donald Trump. He was quick to eviscerate a poorly rolled joint. In 2017, he even appeared in a commercial for Twitter, playing a petulant crank—“How about any song with real instruments?,” he tweeted at Chance the Rapper, who was taking set-list requests—cementing his grumpy-grandpa role on the site. Sometimes he was an asshole, at least per contemporary standards of decorum. When a fan posted an original illustration of him, he responded with dismissiveness: “That is the weirdest painting of me. I have ever seen …..don’t quit your day job ……” When Phoebe Bridgers smashed a guitar on “S.N.L.,” he called the move “pathetic.” (Bridgers, to her credit, volleyed back an exquisite reply: “little bitch.”) Crosby seemed to find the notion of self-censorship stupid, and the stakes online inherently low; this often made me envy him. Such freedom! “Speak out against the madness / You’ve got to speak your mind, if you dare,” he sings on “Long Time Gone,” a heavy and portentous Crosby, Stills, and Nash song from 1969.

As of 2019, Crosby remained estranged, somehow, from Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, and Neil Young. “All of the guys that I made music with won’t even talk to me,” he said in “Remember My Name.” “One of them hating my guts could be an accident,” but, he went on, “all really dislike me, strongly.” One of the last times Crosby, Stills, and Nash played together, in 2015, they delivered an unfathomably pungent version of “Silent Night” at the National Christmas Tree lighting ceremony. Acrimony is evident in the stilted pre-song banter, during which Crosby appears to say more than his share of the lines on the teleprompter. “I can’t believe you,” Stills spits at Crosby, just before he starts strumming the opening chords on his guitar. The sourness between them seeps into their voices. It can be almost fun to watch, in an awkward, “Curb Your Enthusiasm” sort of way, though it is mostly hard to escape the plain tragedy of old friends still unable to make amends.

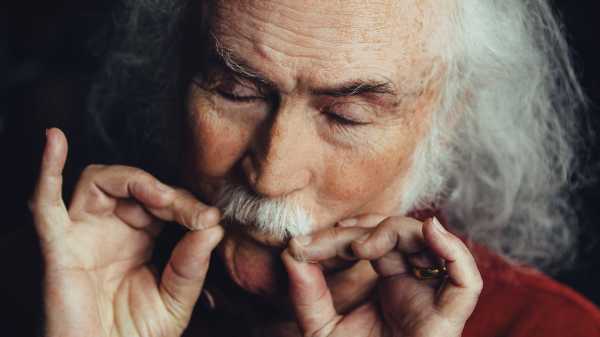

However cantankerous or stubborn Crosby was offstage, when performing, he was seized by a kind of silent joy. You could see it spreading across his face, loosening his features. Music softened him. In his later years, he wore a white mustache, long frizzy hair, and an omnipresent red beanie (knitted by his wife, Jan). He looked like someone who might sell you some garden compost. He looked salty. Performing was the one thing that seemed to reliably animate and excite him.

One of my favorite of Crosby’s vocal performances is a demo of “Everybody’s Been Burned,” a Byrds song from 1967. The tone is somewhere between Nick Drake in his Warwickshire bedroom and Frank Sinatra on a barstool, sloshing a gin Martini. It’s a generous, humane song, about how terrifying it is to go on after loss:

Everybody has been burned before

Everybody knows the pain

Anyone in this place

Can tell you to your face

Why you shouldn’t fall in love again

Crosby’s voice is steady and pure. He understands the sharpness of despair, but he also understands what it means to give in to those feelings. The work, instead, is to transcend the fear. In a way, this was always Crosby’s mission—to overpower darkness, to sing it away. “You die inside if you try to hide,” he cautions. “So I guess, instead / I’ll love you.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com