I waited forty-seven years to see “Walkover,” the 1965 film by the Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski, but you only have to wait a day—it’s screening Saturday at Metrograph, in a retrospective of the director’s work. I first learned of “Walkover,” Skolimowski’s second feature, in the last weeks of 1975, when I was a seventeen-year-old college freshman, reading “Godard on Godard.” He calls Skolimowski’s first two films “a bit like jazz,” and he likened the filmmaker to Charles Mingus. He also said that “Walkover” was one of the three films that he’d most want to write about if he were still a working critic (Skolimowski’s first film, “Identification Marks: None,” was another), and praised Skolimowski for shifting between the “particular” and the “general”: “He describes the individual and the environment at the same time, and probably does it better than anybody else.”

Godard’s specific praise reminded me of the things that I loved best about the few Godard films I’d seen, and the general comparisons to jazz and Mingus might have been meant for me, personally, since I was already a longtime jazz enthusiast and a fan of Mingus. But the vagaries of theatrical exhibition, home video, and life diverged until now; either “Walkover” never played in New York, or I was unaware or unavailable when it did, until I saw it, a few weeks ago.

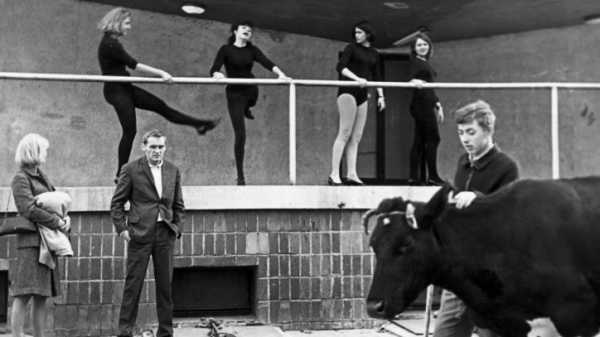

Now that I’ve seen it, I’m not quite sure of Godard’s analogy (at first glance) but I’m entirely in sympathy with his enthusiasm: “Walkover” is indeed one of the masterworks of the brash, youthful, and defiant cinematic modernism of the mid-sixties, a film of a Polish New Wave that shares the insolence, the rejection of authority, and the energies of revolt that also mark the French New Wave (and, especially, Godard’s own films). It’s a quasi-autobiographical story of a young man in crisis at the end of youth; it’s also a sort of duet for one, Skolimowski as director and actor. The protagonist, Andrzej Leszczyc (Skolimowski), arrives by train in a small city the day before his thirtieth birthday. He’s a wanderer in a country of order (under the Soviet-imposed Communist regime), a nonworking person in a so-called workers’ paradise; but, if he’s not exactly looking for work when he gets there, work turns out to be looking for him. A dropout from engineering school, he quickly reconnects with a former classmate who’s a few years younger—a woman named Teresa Karczewska (Aleksandra Zawieruszanka), a successful graduate and a precocious young manager at a huge local energy plant. She brings him into the facility and introduces him to her boss, who readies a position for Andrzej, but the wanderer has an ulterior motive: to take part in an amateur boxing tournament that’s being held there, one in which, as a veteran boxer, he has no business taking part in.

Teresa considers Andrzej a beatnik who’s too old to play that role; Andrzej considers her a Communist Party toady, which sits all the worse with him because he’d been denounced in school on political grounds. Their wrangling and their recriminations don’t get in the way of a quickly brewing romance that’s as turbulent with physical action as is Andrzej’s athletic career. The instant, new couple dashes through the factory site, darts up metallic stairs to an industrial parapet, breezes past heavy machinery, strides with tense determination through a chaotic cityscape of ruins amid large-scale technological transformation. She’s his foothold in official life; he’s her grasp at freedom. She imposes her statistical knowledge to push through a risky energy project (it’s like seeing the seed of a Chernobyl-like disaster planted decades in advance); he impersonates an officer to get them a lift. He carries a dubious collection of watches and a transistor radio (tuned to jazz) that are his prizes from previous fights and that he’s ready to pawn or sell; she is assigned a treasured workers’ apartment. He runs through the streets past a car accident and thus attracts the unwanted attention of police while, moving through corridors and among shady acquaintances like a deft phantom, he plots his return to the ring under false pretenses.

Andrzej’s physicality is an image of Skolimowski’s own—the filmmaker himself was a former boxer, and one of the movie’s surprises, at six decades’ remove from the production of “Walkover,” is its distinct originality as a boxing film. It’s a form of originality that reflects Skolimowski’s depth of personal experience of the sport, his aesthetic audacity and craftsmanship, and the physical aplomb to realize them together onscreen. Much of “Walkover” is done in astonishing, long takes (some reaching four minutes) that rush through workplaces, swerve around desks and peer out windows, bound up and down steps, cross through doorways into crowds, roam streets with brazen confidence—and one of the boldest of these elaborately devised sequences presents Andrzej’s efforts in the ring, where three rounds of boxing are depicted in two extended takes that combine a documentary-like attention to the details of the bout with an existentially tense and danger-packed choreography of maneuvers and blows. The camera even drifts from the ring into the audience (where Teresa sits in the front row) and back, and it keeps going from the end of one round (and Andrzej’s recovery of strength on his stool amid a trainer’s ministrations) to the start of the next one. Martin Scorsese’s “Raging Bull” is a boxing movie second to none, which is, no less than “Walkover,” a vision of the world (indeed, a metaphysical and a religious one) along with a vision of the sport—yet the explosive fragmentation and punishing closeup violence of Scorsese’s graphic boxing images have a more abstract and philosophical terror than Skolimowski’s sense of real-time mortality in the balance.

That feeling of danger comes through all the more strongly in another scene, one that involves—spoiler alert—a leap from a moving train, pulled off by Skolimowski himself, that is far scarier to witness than anything Tom Cruise attempts in the “Mission: Impossible” films. (Yet Skolimowski’s daring extends outside the physical realm to the textual one, by way of interpolated images, extended closeups of Andrzej, matched with voice-over recitations and performances of poetry—ostensibly his own, inasmuch as Skolimowski himself is also a poet.) The complex organization of the movie’s teeming intricacies never feels stiff or restrained; it retains, along with Skolimowski’s onscreen presence, a feeling of freedom—despite Poland’s political circumstances—that may well be the movie’s closest connection to jazz. “Walkover,” had I seen it around the time that I’d found out about it, would have had the salutary effect of expanding, from the start, my sense of cinematic possibilities, of realms of invention and expression that combined personal experience and pugnacious social observation with a singularly bold and original style.

Strangely, “Walkover,” though I waited longest to see it, was far from the rarest of great films that I’d read about in that same book of criticism. The mid-seventies were a moment of odd unavailabilities, of a sort that seems nearly incomprehensible now. Home video was still in its infancy, and almost all movie viewing took place in theatres by way of circulating prints (or ones in museum collections), or else, the happenstance of a television broadcast (almost always punctuated by commercials). In a 1963 poll of the best American talking pictures, Godard named Howard Hawks’s 1932 gangster film “Scarface” No. 1 and put Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” in third place (with “The Great Dictator” between them); but, at the time that I read this, in 1975, neither film was available; both were held up by contractual issues. “Scarface” reëmerged in 1979, after more than forty years out of circulation, and “Vertigo,” unavailable since 1968, didn’t get reissued until 1984.

I’ve waited even longer for other movies; for instance, I was able to see only fifty minutes of Ermanno Olmi’s “Il Posto,” during a corporate-office lunch hour, some time in the nineteen-eighties, and had to wait another decade to see its final forty-three minutes. But the most grievous unavailabilities are the ones that fit into the category of the unknown unknowns: every great rediscovery marks a gap in the history of cinema that’s also a gap in the history of inspiration. William Greaves’s radically exuberant and self-critical docu-fiction “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One,” from 1968, wasn’t released here until 2005; Michael Roemer’s dryly extravagant Jewish-gangster comedy “The Plot Against Harry,” from 1969, was released only in 1989; Kathleen Collins’s “Losing Ground,” from 1982, came out here in 2015; Zeinabu irene Davis’s “Compensation,” from 1999, never had a U.S. theatrical release at all. They’re films I didn’t know that I was waiting for, that, in fact, the world at large was desperate for without realizing it. At least the Hawks, the Hitchcock, even the Skolimowski film (which played at the New York Film Festival in 1965 and had a 1969 theatrical release) took their places in history, filtered into young filmmakers’ consciousness through reports, reviews, word of mouth, even legend. The great films that aren’t seen in their moment at all tear holes into the future; their absences are the blocking of paths. Even now, the contingencies of commercial releasing and the troubles with distribution aren’t only crises in the business of movies—they’re deprivations for every potential filmmaker, threats to the future of the art. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com