Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

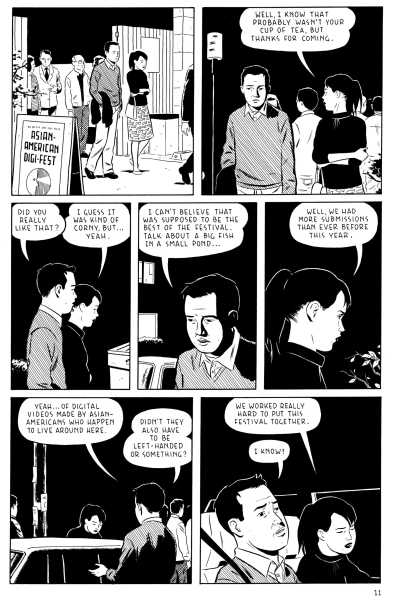

The latest comics-to-film adaptation, “Shortcomings,” Randall Park’s directorial début, will be released on August 4th. It is based on Adrian Tomine’s graphic novel of the same name, which was one of the most significant works to emerge from the independent comics scene in the early two-thousands. In the movie, as in the book, we see the world through the eyes of Ben, a young man in Berkeley, California, who stumbles his way through love and his feelings about his Asian American identity.

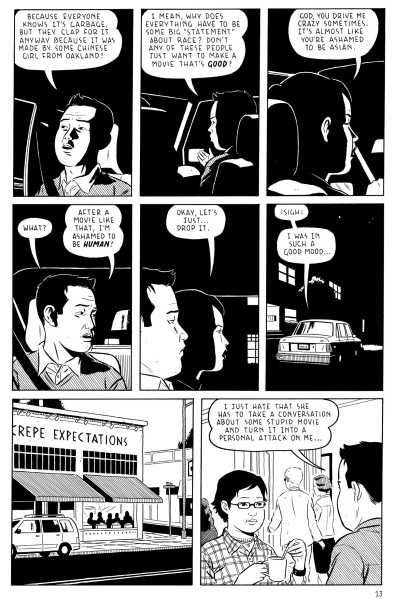

Tomine first made a name for himself through his self-published series of mini comics, called “Optic Nerve”; the stories displayed the seemingly magical power of Tomine’s comics to capture the messiness of life on a page. Thanks to his impeccable design sense and his sensitive ear, the author and artist wields expressions, gestures, panels, pauses, and speech balloons to chart out his protagonists’ emotions: angst, ease, and all the nameless in-betweens.

“Shortcomings” is not the first film adaption of Tomine’s work; the French director Jacques Audiard drew in part from Tomine’s collection “Killing and Dying” for his 2021 film, “Paris, 13th District.” But, this time around, Tomine was involved in the filmmaking process, acting as screenwriter and working closely with Randall Park. I spoke to Tomine about what it has been like for him to revisit his old work, and how he endeavored to usher it into a different medium.

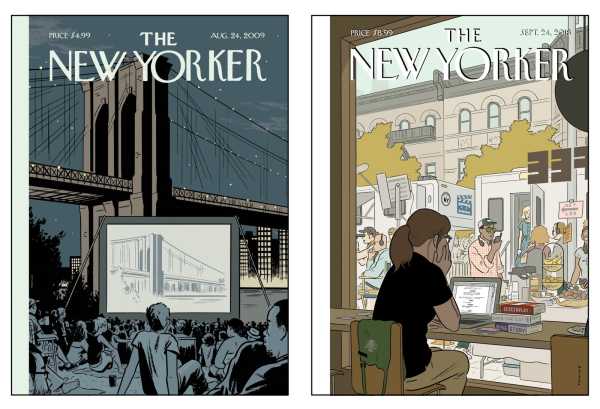

You have long been interested in movies. I remember your 2009 cover about outdoor films in Dumbo and the 2018 one with a screenwriting barista watching a film shoot.

Yes and, as a matter of fact, I drew the barista one while writing the screenplay for Randall’s film. That was my experience: sitting there writing this thing, not knowing what was going to happen to it. And—at least this was true until the strike—everywhere you went in New York, it seemed like people were filming things.

For the poster announcing the film, which will be released on August 4, 2023, Tomine drew the actors who had used his drawings as models.Courtesy Adrian Tomine

What’s your relationship with a work that you made and published such a long time ago?

Well, at first it was tough. I don’t go back (of my own volition) to read my old work, but I was forced to do it for this project. Intellectually, I know that I’m the person who wrote and drew it, but I also feel that so much in my life has changed since that time. I started writing the stories over twenty years ago. In the years since, I moved from California to New York, got married, and became a parent twice over.

In a way, it was less painful to revisit this work than something from a few years ago, because it was so distant—it felt like the work of some young single guy from Berkeley, rather than something that I did recently and would still want to fix and change.

Did the need to adapt comics for a different medium help?

Yes, it helped to work with a team. One of the first discussions that came up was someone asking, “If we adapt this, do you think it should be a period piece, or should it be present day?”

In my mind, at my age, anything after the year 2000 seems like the present day. But I went back and looked at the book and saw there are all these anachronisms. There are a lot of dramatic moments, like people angrily slamming down landlines. There’s also a whole plot point where someone is in New York and they want someone in California to see something—without an iPhone, they actually have to say, “Hey, come out to New York—I want to show you some things.” So, yes, it also made me feel old.

And which way did you end up leaning, making it a period piece or present day?

Present day! Someone explained to me that to make it a period piece set in the early two-thousands, it would cost much more money. Every car in the background would have to be from that year, and all the clothes would have to be accurate and everything. And I said, I don’t think it really adds much for all that money. So let’s set it in the present day and just film what these locations look like now.

Do you feel a kinship with people who are now in their twenties and are reading your work or seeing the film?

I’m like the man with two brains or something like that, because I keep having this kind of shock when people ask me what it’s like revisiting these young characters. And I’m thinking, What are you talking about, young? I’m just like these guys. I still feel very connected to these characters. I had a great time writing them and rewriting them and updating them. And I love the actors that are playing them, too. I’m sure they thought of me as the old guy who’s coming to visit the set, but I thought of them as my friends.

Then there are other times, especially in other parts of my life, where I feel old. Like an old dad getting angry when kids who are too old are using the swings at the playground—things like that. Which of those modes I’m in really depends on the hour or the minute.

Do you think that the internal life of somebody coming of age now is similar to what it was twenty years ago, or has it radically changed?

I would have to be pretty oblivious to think that there haven’t been fundamental changes in what life is like for young people. I know better than to try and speak with authority about what it’s like growing up with social media, or to have had iPads since birth, or anything like that. So when adapting the book I didn’t want to try and speak to something so monumental. But it is ultimately a story about relationships and introspection and self and finding your identity—a lot of core experiences and emotions. I focussed on things that I thought were universal not just between generations but among people, too. I felt like there were things about these characters that I could still relate to—that people my age could still relate to.

I also put a lot of faith in my collaborators. I told Randall Park, the director, that I wanted the script to be improved by the actors. They are living lives closer to that age, maybe closer to the characters, than I am. They grew up in a different world than I did, so I was very open to the idea of them improvising, changing things, correcting me. And I think the movie is better for it. I really think of the version of the characters that are on screen not as my characters brought to life but something new that’s a collaboration between me and the director, the actors, the costume and the hair-and-makeup departments, all these people who work together. It’s exciting to see it go out in the world and connect to a new audience.

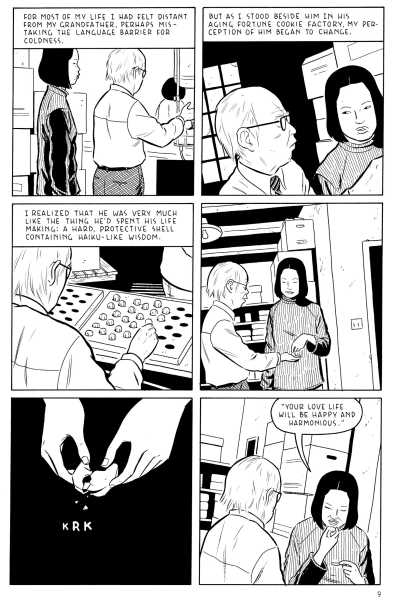

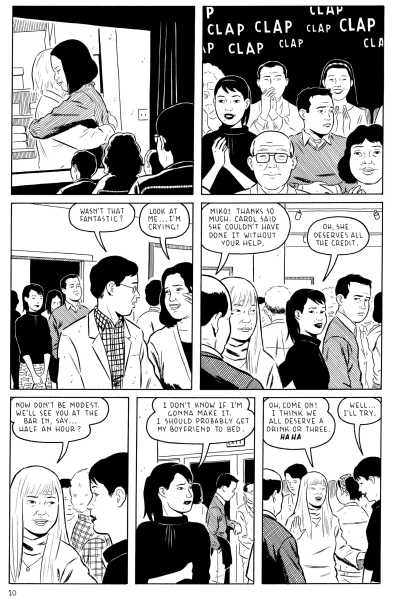

See the characters introduced in the opening pages of the book “Shortcomings” below:

This is drawn from “Shortcomings,” published by Drawn & Quarterly, in 2007.

Sourse: newyorker.com