Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

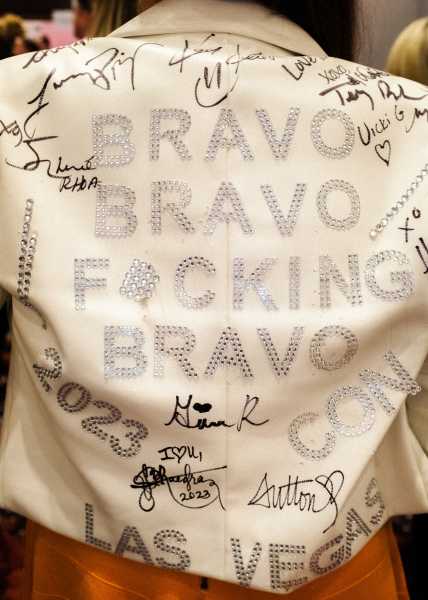

Thousands of romantics, driven to the desert. This year, the reality-television network Bravo held its third annual fan conference, BravoCon, in Las Vegas, dumping the Javits Center, its previous locale, for the pillarless ballrooms of Caesars Forum. Returning attendees rated Caesars a vast improvement. The corporate barracks of the Javits, by the West Side Highway, in New York City, had a gray spirit that encouraged fights, light stampedes, and nervous drinking. There also weren’t enough bathrooms. Our bladders were bursting, some returnees reminisced, when I met them at this year’s event, in early November.

When tickets for BravoCon went on sale, in July, they sold out in a day. A V.I.P. pass for the three-day event went for well over a grand, a price that does not include all the extra costs that one accrues while in Las Vegas. The attendees had paid for the right to be critical; this scrutiny is also what defines Bravo fans, who are often referred to as Bravoholics. A Bravoholic is a romantic in that she is obsessed with the fantastical world that Bravo offers, but this does not mean that she is loath to criticize the network. Still, she is turned on by the feeling of being captive and addicted. At Caesars Forum, the lines for the toilets flowed well, and there was even a dash of interactivity to the experience, provided by Clorox, which, to invoke the pillage language of advertisement-speak, “took over” the bathrooms at the conference. In the restroom mirrors, framing your hungover reflection, were brand appropriations of taglines from some of Bravo’s biggest stars, themed around the pun of interpersonal drama as mess. (A koan from Dorit Kemsley, of “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills”: “I believe in excess of everything—except moderation.”)

A romantic does not spend thousands of dollars on tickets, hotels, airfare, food, and drink because she seeks to be hustled as she urinates. A romantic accepts the flood of advertisement theatre at BravoCon because the event promises her real fourth-wall breaking. Executives at NBCUniversal, Bravo’s parent company, and fans on the ground parrot one another: You come to the Con for a mental escape. BravoCon is the natural evolution of an inorganic corporate entity. The virtual consumption of human story while watching reality television becomes temporarily, and weirdly, physical.

Brynn Whitfield, a new addition to the “Real Housewives of New York City” cast, with her Louboutins.

A worker outside Caesars Forum.

The Con teems with millennial and Gen X women (the majority of them white), slightly younger gay men, and the occasional supportive straight male spouse. Something banshee emerges when they come together, as Bravo fans take on the attitude of a subculture. Strangers buy one another sixteen-dollar glasses of rosé and novelty T-shirts. (A refrain I heard from many of the older women was that they did not “normally do this sort of thing.”) A public voyeurism among the same sex is one of the main undercurrents at the conference. It is not uncommon to overhear real-time evaluation of a star’s body, or her makeup, her pores made vulnerable sans the network’s blurred-light cinematography. Straightish women use gay slang to express their appreciation or distaste: one star “served cunt”; another was “beat down.” The medieval ambience of the word “fandom” fails to capture the attractive aspect of Bravo fans, who are not moonstruck lovers of the network’s properties. A Bravoholic is a critic and a judge. She prefers to live outside of the fantasy, as so much pleasure is to be had in her analysis of it. How she watches her stories is a rebuke to the Netflix model of passive viewership. The voyeur at home has always wanted to activate her gifts of judgment—to produce the action, in other words—and at the Con she finds herself “on set.”

There are the Bravoholics, and then there are the Bravolebrities, or the more than hundred and sixty reality stars, on the network’s series. You don’t have to be a completist to have seen the imprint of their programming, the most recognizable being the “Real Housewives” and “Below Deck” franchises, and more niche hits, such as “Married to Medicine” and “Southern Charm.” At BravoCon, the stars of these series work, basically, for seventy-two straight hours, showing up for scheduled events. Most are question-and-answer panels, with a vibe similar to the reconnaissance-and-comeuppance dynamic of the “reunion” episode, the coda that comes at the end of each season, when the cast goes meta, reviewing the tape. Nighttime events, most of which cost extra, are campy live tapings that would be repurposed by the network. Soft news might break during a panel or a junket: a divorce, a spinoff, a cross-property feud. But nothing revelatory, as stars have been advised by NBC executives to save the best drama for production. As Andy Cohen, an executive producer of the “Real Housewives” franchise and the host of the late-night talk show “Watch What Happens Live with Andy Cohen,” told me, “You don’t need to bleed out there.” “Housewives”—consisting of dozens of shows, including its international series and spinoffs—is the crown jewel of the Bravo empire, and Cohen acts as the daddy figure of the network. At the Con, he is the de-facto master of ceremonies. It is his job to cultivate an atmosphere of risk. “BravoCon needs to feel uncensored and authentic,” he said, “and not like canned television.”

The conference was a flood of advertisement theatre, with many sponsors seemingly hungry to hitch themselves to the conversion of the Bravo viewer into the Bravo customer.

An attendee wears a shirt bearing the mug shot of Luann de Lesseps, a former cast member on “The Real Housewives of New York City.”

I’d arrived in Vegas for the last day of BravoCon, knowing that the excitement had somewhat dampened, the voices now hoarse. During a cab ride from the airport, I watched a clip of something that had happened the previous day: one Bravolebrity, Brynn Whitfield, a new cast member on the “Real Housewives of New York City” reboot, had a mishap as she was walking to her panel. Her Christian Louboutin heels got stuck in the escalator, and she had gone to her talk barefoot, her heels left behind, like the remnants of a crushed wicked witch. The taxi-driver apologized for the unusual morning traffic. Preparation for the Formula 1 Las Vegas Grand Prix, scheduled for mid-November, snarled Koval Lane, on the way to the Strip. Unions representing thousands of hospitality workers had threatened to strike, jeopardizing millions of dollars in race revenue, if the casino operators did not meet their demands. (The unions and the resorts have since reached a provisional deal.) The transience of the tourist, the intractability of the laborer. In comparison to the Grand Prix, and to the Super Bowl, which will take place at Vegas’s Allegiant Stadium, in February, BravoCon is a modest intrusion.

Bravo itself has been embroiled in a labor dispute of its own. The novelty of the network, once pilloried for the sins of sexism, exploitation, and artlessness, has long dissipated; Bravo is now a synecdoche for a recognizable postmodern entertainment. The company’s retooling of what we know as women’s media has betrayed its ultimate function as a workplace. Bethenny Frankel, a former star of “The Real Housewives of New York City,” has been garnering support for a union, which doesn’t exist for reality-show performers. And so the Con, this year, served double duty: an expensive party, and a distraction from the distraction of a potential uprising.

Labor was on my mind as I approached the Forum. It was the contract workers, hired out to Caesars by event-staffing companies, who greeted me at the entrance, and who provided the first faces of the BravoCon experience—faces, I’d learned, from a contractor who cheerfully violated the no-talking-to-press rule, that had been asked to adopt a cataract of friendly forgettability. Vegas P.D. officers, avoiding eye contact, briefly upped the anxiety around the reality of mass gathering. I walked to security, where I was asked if I was carrying any knives or guns. Stanchions created separate processing lines for the V.I.P.s and the standard-admission guests. The former got the best seats and the shortest lines. You could also pay for entrance to BravoPalooza, a lounge experience at the Forum, where the miniature burgers and margaritas were free and where one could rub shoulders with the Bravolebrities. The night before I arrived, guests who had either snuck in or paid four hundred and forty-nine dollars had gone to “BravoCon After Dark,” at the OMNIA Nightclub.

Andy Cohen, the king of Bravo.

The Forum gaped at you, a faux Hellenic garage opening on a bleached plaza. You could get your bearings in the anterior outside space, the dining tent, which was empty and a touch dank at nine-thirty in the morning. The lone people buying refrigerated sandwiches there got absorbed into groups. Holly, a former model, who flew in from Canada, reminded me of Margot Robbie-as-Barbie in her baby-pink short-suit set. (It was early in the day, but it was almost seventy degrees outside.) Holly had met about forty Bravo stars at the Con. Would I meet her, that evening, at a live taping of “Bravocon Live with Andy Cohen!” at the Paris Theatre, a five-minute drive from the Forum? Lisa Vanderpump, formerly of “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” now the mother muse of “Vanderpump Rules,” owned a restaurant at the Paris hotel; we’d find plenty of Bravo people posted there. Other fans, I’d learn, had found canny unofficial ways to come into contact with their chosen divas. You’d waste time waiting on a photo-op line for Karen Huger, the Grande Dame of Potomac. Better to stomp strategically around the peripheries of the Con, where black cars rolled up to the V.I.P. entrance, or to abandon the Caesars complex altogether for the Four Seasons. (Uber drivers had let slip that many of the stars were staying there.)

This was not gauche behavior. Fame here leaves the Hollywood model of oversaturation through mystery and distance. This is oversaturation through oversaturation. A Bravolebrity’s identity has at the forefront, regardless of personal net worth, the status of employee, one that is not forever. And it is the fans, not the parent company, that gives them this sense of existential employment. Cohen told me that he had felt “territorial” when an entertainment blog reported on a fan-produced podcast, some years ago. Since then, a secondary industry has ballooned of self-identified content creators, many of whom support themselves entirely through their cultural-digest shows. The network depends on their output, Sarah Galli, of the long-running podcast “Andy’s Girls,” told me, as such creators keep the show going well after an episode has aired. At the Con, some were as famous as the Bravo stars themselves, their presence causing mini-floods.

Teresa Giudice, from “The Real Housewives of New Jersey,” with fans.

At 10 A.M., my phone lit up with a hot-pink notification from the BravoCon App, encouraging me to buy a drink. A playground opened before me, inside the Forum, its energy a mash between an industry Upfront event and a booze cruise. There was the Bravoland museum displaying iconic artifacts from classic seasons: a set table that had been flipped in fury, hot tubs from a spa day gone bad. Interactive booths allowed fans to film their own “confessionals,” the interviews where producers prod stars for critical asides. If you looked lost, pacing the massive carpeted hallways of the Forum, a man might blow a kazoo in your face, bidding you to buy themed apparel. When it came to dress, among the streaming fans there were two schools of presentation: relaxed, sensible shoes, possibly sporting a “Bravo Lovin’ Bitches” T-shirt, and then conspicuously glammed, as if wearing Housewives drag. The glam girls tended to end up at BravoPalooza, where they could socialize with stars as pseudo equals. And aren’t they, if not equals, then at least in a symbiotic state of being?

I entered a crepuscular, enormous space called the Gold Room. Catercornered to the bar was an immersive living room sponsored by Wayfair, a re-creation of the winter opulence of the Salt Lake City “Housewives” franchise. Wordlessly, a BravoCon worker gestured toward their chest and handed me a package of breast-lifting tape, gratis. Only about half the room filled up for the first program of the day, “Pat the Puss with Erika Jayne,” a dance class which was itself an advertisement for a spinoff for the Beverly Hills Housewife which would première next year, about her Vegas residency. With her lion mane and second-skin catsuit, Jayne, who tries hard to affect pitiless self-interest on the series, seemed smaller, near to sweet. She made sense only blown up on the enormous screen hung above her from the ceiling, her real environment. Its light gave her her harshness.

The fans brought up onstage to learn choreography with Jayne were happy and pliant. At other programs, the audience response was vitriolic. A known philanderer from “Vanderpump Rules,” Tom Sandoval, was booed each time he opened his mouth; Jennifer Aydin, from the New Jersey “Housewives” series, was asked by a fan, during the Q. & A. portion, when she’d stop crawling up the asshole of her castmate. A peculiar contract of reciprocity becomes live at the conference. Dislike counts as popularity. I met two sisters, Stacey and Renée, from Colorado, co-owners of an Orangetheory fitness. They identified as the sort of fans who had too much self-regard to take selfies with stars. They had tough words for Teresa Giuidice, a New Jersey O.G. who had returned to the fore after serving time in prison. “I’ll be honest with you, they shouldn’t have brought her back,” Stacey said. “She broke the law.” At one panel, Giuidice shrugged off boos. She has said that she’s not leaving until Bravo fires her.

Ariana Madix (far left) and Katie Maloney, from “Vanderpump Rules,” filming with a crew.

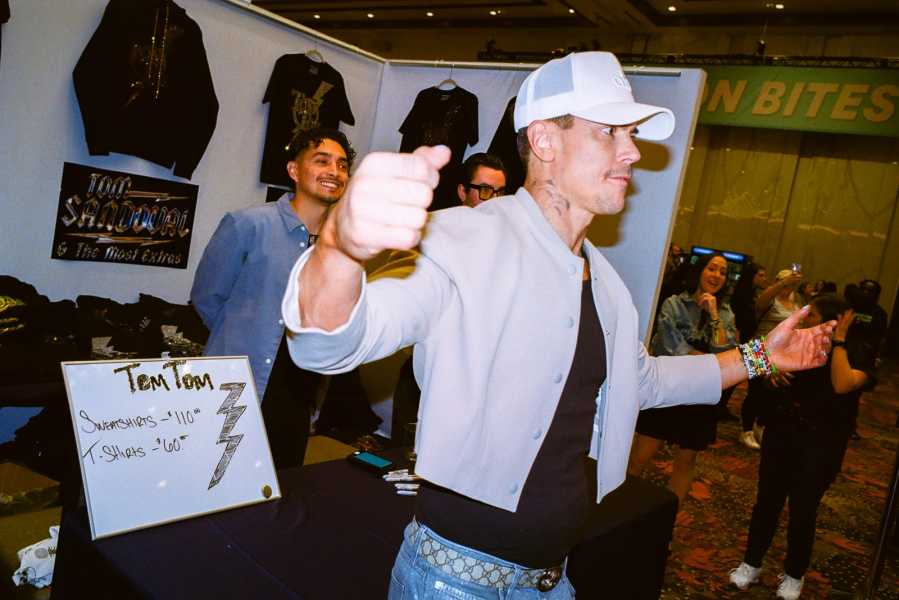

The “Vanderpump Rules” star Tom Sandoval selling merch in his booth.

Adjacent to the Gold Room was the Bravo Bazaar, a mall of real commercial rapacity. I learned a word in Las Vegas: “shoptainment.” At the Bazaar, there were more than fifty booths one could browse, the majority dedicated to the stars’ businesses. (Some were tied to story lines, like “SHE by Sherée,” the beleaguered clothing line launched by the “Real Housewives of Atlanta” anchor, Shereé Whitfield.) Periodically, stars came out to personally hawk their products. Two Bravoholics, Sara and Summer, best friends from San Diego, talked of the “parasocial” draw they felt toward Sandoval, who was taking pictures near his eponymously named booth. They were, in their early twenties, experts at analyzing the psychology of pop-cultural product. “I do not talk highly of that man, not one bit,” Sara said, of Sandoval. “But here I am in line to wait.”

Men are simpler creatures when it comes to advertisement. “It’s harder to get women to wait on line for x amount of minutes to meet Craig Conover to buy his pillows,” an NBC ad executive told me. The Bazaar fomented the hot sororal atmosphere that leads a visitor to make claims about the American woman consumer substantiated only by anecdote. Sellers drew you in using irony, flirtation, embarrassment. Being advertised to is an experience of being noticed. The employee at the Juvéderm booth, a company that sells fillers, asked for customers’ names, and then shouted at them as they gamed the claw machine. Predictably, the beauty industry had sent its emissaries—Ulta was a sponsoring partner—but the tell was in sponsor companies like Lay’s, the aforementioned Clorox, and State Farm Insurance (the actor who plays Jake in the commercials acted as beefcake at one booth), which were hungry to hitch themselves to the conversion of the Bravo viewer into the Bravo customer.

Feeling hungry, I ordered chicken fingers at a station called Bravo Bites. The waiter refused to give me the meal, insisting it was disgusting, and suggested I eat two cartons of mixed fruit instead. As I plodded back toward the Sandoval zone, a Black woman of about seventy years grabbed me by the shoulders, nearly shaking the fruit out of my hands. Did I know where the panel with Vicki Gunvalson, part of the inaugural cast of “The Real Housewives of Orange County,” the début series in the franchise, would be? The woman had been brought to BravoCon by her daughter, who didn’t watch reality television herself. She had been a widow for eight years, and yet the absence still felt new. “It takes you away sometimes,” she said, of Bravo, showing me selfies she had taken with the cast of “Summer House: Martha’s Vineyard,” a new anatomy of Black social life on the island. She detected a humility on “Summer House” that she found refreshing. Whereas on “Housewives,” she said, “It aggravates me the way they don’t appreciate what they have, because a lot of them are childish. It’s humorous,” she continued. “It’s sad.”

The woman left to find her daughter. I wandered up the stairs for “Housewife2Housewife: Day One Divas,” hoping to find her again. I wanted to hear more of her thoughts on the racial tropes that reality television subverts, those of the “Black bitch,” and “white women fighting.” I never found her, but I did meet a nurse practitioner, who was waiting for a friend to join her in line for the panel. As we moved through the stanchions, the nurse explained that she and her friend, who work at the same clinic, had been ghettoized by their colleagues for their interest in Bravo, which had seemed, to some snobs, beneath their intelligence. I’d have thought this argument to be passé. What is interesting about Bravo is that love for its programming has created snobs of its own. There was no bottom to conversation, I found, with the fans I talked to, who iterated with total fluency on the performance of womanhood. Where else can that be done?

Four days before the Con, Vanity Fair published an article about Bravo that the magazine packaged as a reckoning. The reporter outlined displeasure with labor practices from former Bravo employees, some of whom felt that the show’s emphasis on alcohol and fighting created an unsafe environment. The report had led to the banishment of Ramona Singer, a long-running figure in the Bravo behemoth, from the conference, after she was exposed for allegedly using a racial slur. (She has denied this.) But, otherwise, the Con betrayed little in the way of moral outrage. Bravo metabolizes offense. Emily D. Baker, a Los Angeles lawyer who has found so much success as a YouTube commentator that she abandoned her legal-consulting practice, was expecting more of the Bravo stars she talked with in Las Vegas to “give more of a shit” about the issues raised in the article. “They talked about their own behavior on the show, their own autonomy, and how they choose to engage with Bravo,” she said. “I was surprised by that.”

My night ended with a taping of “Bravocon Live with Andy Cohen! The Reading Room,” at the Paris. I recognized Holly’s blond pate from afar but lost her in the fray outside the Vanderpump restaurant. Cohen pranced onstage, with a selection of Housewives close behind him, and then we started taping a game called “Squash That Beef,” a riotous fan favorite. Two randomly selected stars are put in the hot seat. Their bad blood is brought up, and they have the option to dig in or move on. The event’s hype woman had been stern about being quiet once the cameras started rolling. But one defensive monologue drove an audience member, a woman in a moto jacket, to true annoyance. She stood up and yelled something intelligible, and then sat back down, but the stars kept up their bickering, seemingly unfazed. Had the woman got away with the outburst? For a few minutes, it seemed like it, but then security came and whisked her away.

Sourse: newyorker.com