Marginal declines in middle-class standard of living are graver than they seem.

My great-grandmother was a widow in 1966, in her mid-50s watching the only city she had ever called home collapse before her eyes. She sold her three-level house in Dorchester—until that point a stable, safe, and unusually diverse middle-class Boston neighborhood—and moved out to the suburbs.

She settled on a three-bedroom, split-level ranch on a quarter-acre lot in Rockland, about 20 miles south. Her parents had come from Ireland in the 1880s, and (at least this is what my grandmother told me) she bought the house because it was green, which called to mind a motherland where she had never lived. The house cost $22,000—about three times the median household income nationwide that year. Pegging the value to that same figure, it would take about $225,000 for a family to buy the place today.

My grandfather died two years ago, the last person left in a little house that had held four generations over time. We cleared out 60 years of accumulated crap—most went in the dumpster, though I took some furniture—and my mother sold the house for $400,000.

Assume the same proportion, though: three years’ salary to buy a place to live. That puts the actual minimum purchaser in the 75th percentile of U.S. household income. This for a small family house in a middling town on the outer edge of a fading metropolis.

By virtually any measure, Rockland is a worse place to live than when my great-grandmother moved there during the Johnson administration. Most of the businesses downtown have been shuttered. The parish school that my siblings and I attended (and where my parents met as students in the ‘80s) closed five years ago; it is being converted to low-income senior housing. The public schools are famously unimpressive. Violent crime is fairly low—nothing like Dorchester after the old families fled—but petty offenses are higher than they should be, and the opioid epidemic is as bad in Rockland as anywhere. There is a commuter rail station in the next town over, but beyond that the rise in housing prices is not tied to anything discernible on the ground.

There is a real challenge here that the optimistic and numerically inclined are eager to dismiss. At a particular time in a particular place, American families are expected to spend more for less. They are expected to stomach real declines in quality of life in exchange for a mess of pottage. They are told that everything is getting better, regardless of how it seems. The assurances grow weaker every day. In the mind of the average American worker, macroeconomic witchcraft and growth-mindset wishcasting are irrelevant. What does it matter that a Whole Foods has opened up the street when your housing payment triples?

At medium-scale, the picture is no better. There are twelve properties listed for sale in Rockland at the moment of this writing. Up on the very edge of town, there is a two-bedroom house under 1,000 square feet listed for $375,000; it is a very short drive to the Whole Foods in Hingham. Another tiny two-bed is going for $400,000, and an as-is three-bed is a steal at $390,000. There are 25 undeveloped acres listed for $1.5 million, and a ten-unit multifamily listed for $1.2 million. There is a trailer in a retirement community for a mere $260,000. The other six range in price from $550,000 to $900,000.

You can go out further. In fact, that’s what my parents did. As newlyweds in 1996, they bought a one-bedroom condo in Marshfield, a quaint coastal town not far from Rockland. (My grandmother’s cousin fled Dorchester around the same time she did, broke into construction, and built large portions of the town. He now lives on the homestead of Peregrine White, who was born aboard the Mayflower, on the west bank of the South River.) It was not a pretty place. They were among a few owner-occupants in the complex; most other units were leased out to illegals. The living experience gradually declined, and my dad finally decided it was time to go when an unknown culprit pissed in his basket in the communal laundry room. (To this day, he gets visibly angry when you ask him to tell the story.)

At the end of 1998, with your humble correspondent in utero, they moved out further still, to Plymouth. This was a return of sorts: Our first American ancestors had settled in Plymouth in 1620, off the same ship where Peregrine White had burst into the world. They bought a three-bedroom Cape in a quiet neighborhood, with a yard three times the size of the little green ranch in Rockland. I think it cost $120,000—again, right around that benchmark of three times the median household income.

Again, then, the 2023 price should be about $225,000. It sold this summer for exactly double that.

The market in Plymouth is much bigger than Rockland—137 listings altogether. There are quite a few trailers (mostly, again, in retirement communities), some undeveloped lots, and a teardown or two. But the real single family homes—places where you could settle down and raise kids, properties in whose long-term prospects you can have just a little confidence—start at $550,000. Seventeen are over $1 million.

Plymouth is a nice place. It’s a beautiful coastal town with plenty of forest and ponds and an abundance of historical character. But just 25 years ago it was the kind of place a middle-class family would go for a reasonably easy start. For a while on either side of the late ‘90s, suburban neighborhoods popped up practically overnight in what had been the empty woodlands of a sleepy seaside village. In its first three and a half centuries, the population had never cracked 20,000 souls—even when the Plymouth Cordage Company was a worldwide powerhouse. In the past fifty years, the town’s size has more than tripled, to just over 60,000.

Those neighborhoods still pop up here and there; the last time I visited my parents, a whole new street had materialized a few hundred yards from theirs. There are still plenty of woods. But most new construction now is condos and apartments. The kind of lifestyle my parents came here for is no longer even entertained as a possibility for families of similar means. If you can’t buy in Rockland and you can’t buy in Plymouth, what are you supposed to do?

I suppose you could keep retreating. Just beyond Plymouth is Wareham, where a few decent family homes can be found for less than half a million. There are tradeoffs—it is far from the highway, farther from the good schools, and the economy is not as thriving as the commuter hubs and tourist traps nearby—but that’s to be expected. The town has a less than stellar reputation, but somebody has to be the vanguard of gentrification. But then what? You can’t go much further than Wareham; you’ll wind up in the ocean.

The reasons for all this—explanations as to why housing prices have become decoupled from the economy at large—are the subject of another essay. At issue here is the effect: The kind of homeownership expected by the middle class of this country a generation ago is largely closed off for their children. Millennial and Gen Z home buyers will be expected to pay more for less, in a worse location, at a prohibitively high rate of interest. We will see higher rates of renting, higher loads of debt, and drastically lower satisfaction with economic conditions and the overall trajectory of the country.

The great cities of midcentury America turned to cesspools of crime and poverty from the 1960s onward. The middle class fled to places like Rockland, which became either prohibitively expensive, overrun by the same vices as the cities, or both by the end of the millennium. A second flight ensued, with small towns and outer suburbs bursting in population. The American dream has left those places too, now—at least for the bottom 75 percent of the population. It is hard to describe this sequence as anything other than collapse, and it is even harder to imagine how we might turn things around.

Admittedly, this is not the whole picture. A return to the standards of 1966—even to those of 1998—may entail some surprising improvements, but it would also require sacrifices.

My grandparents never had to buy a house. That meant they could enjoy a middle class lifestyle at relatively low cost, and it made their long-term prospects drastically more promising than a worker of their station could expect today. It meant a relative degree of security even when they fell on hard times. They sent my mother to college, an expense that would have been unthinkable to the middle class of a generation earlier.

It also meant they had to live with my grandmother’s mother. Conservatives understand the potential benefits of a multigenerational household well enough in the abstract, but how many of us really want to raise kids under one small roof with our in-laws? If we packed in the way previous generations of Americans did—and the way families still do in most countries on the globe—then we could nearly wipe out the questions of debt and renting among the middle class.

Then there are the smaller facts. How many other ways has our standard of living changed in the last fifty years?

My great-grandfather was a chef. (Another of my grandmother’s favorite legends was that Jack Kennedy, a friend and regular customer at the Ritz-Carlton in Boston, had promised to put him in charge of the White House kitchen if he ever got elected.) But the variety and quantity of food that was available to him and his family were dramatically lower than what’s on the table today. I have two different grocery stores within two minutes’ walk from my apartment. There are more restaurants in my neighborhood than I could ever hope to try, and nowhere does dinner cost more than a few hours’ wages. In 1966, a meal out was a major luxury.

My great-grandmother was a God-fearing Irish Catholic. She visited Rome once, then the old country in her old age. I am not sure she ever traveled anywhere else. I suppose I have already seen more of the world than even very recent ancestors would have seen in a lifetime. My mother grew up in the little green ranch with a tiny black-and-white TV; I have a 55-inch flatscreen. The iPhone alone is a marvel—one available not just to middle-class professionals but to virtually every member of society.

Revealed preference over generations suggests that we really want these things. We have chosen major tradeoffs in the long run, and we choose the little ones every day. If I ate less steak and more meatloaf, if I did not own a car, if I wore the same suit to work every day, maybe I would own a ranch by now as well. Or maybe not. The world in which the common man (or his widow) could buy a decent home on three years’ pay is gone now—at least in the part of the country I call home.

There are details elided here, and yearslong stretches that must have been very hard. I do not mean to dismiss the struggles of generations past. But that is exactly the point. On virtually every count, my life, my siblings’ lives, are better than our forerunners could ever have imagined. And yet there is this overpowering sense of worseness. Land, a house—that is real property. What are the other improvements worth if we can no longer attain that?

Maybe I am a bit out of touch. A chef is a skilled professional, and I suppose the true middle class has always been half a step lower than my point of reference. How many people really owned three-bedroom houses in 1966? A great deal of the midcentury lifestyle was underwritten by cheap housing—not just affordable, cheap. The aluminum boxes that went by the thousands to veterans and their families in the ‘40s and ‘50s are not even standing now. There is a reason for that. Maybe the problem boils down to lifestyle inflation. There are plenty of trailers and cheap houses in this country, and plenty of room for more. There are prefabricated buildings not unlike the mail-order kits of old. We dismiss the Lennar shantytowns popping up nationwide as “dystopian”—you will live in the pod, you will eat the bugs—but how different are they really from our past?

History moves in circles. My sister lives in Dorchester, in a tiny studio apartment where rent is $2,000 per month. She is hardly alone there. Quite a few of my friends from high school have moved back to the old neighborhoods—Dorchester and South Boston in particular—that our grandparents were chased out of in the last century.

It is an almost literal process of dispossession. Two and three generations ago, middle class families were forced to abandon their homes in search of safe streets and functioning schools. For half a century, the neighborhoods they left behind were ravaged by crime and drugs, and the buildings were left to rot. Now, the ruins are being leased back to their descendants at a premium. There could hardly be a better illustration of the betrayal of the middle class. They are fine—they have housing, and jobs, and maybe some money in the bank. But they are worse off than they should be.

What are the other options? It is not quite true that you can go no further than Wareham; only one direction will put you underwater. Even in Massachusetts, there are towns to the west with affordable real estate, relatively speaking. And then there is the whole rest of the country. In Texas right now, there are more than 15,000 homes listed with two bedrooms or more for under $225,000—3 times the median household income. In Pennsylvania, there are more than 8,000. (In all of Massachusetts, there are 213.)

This has always been a country of frontiers, and resettling may be part of the solution. That would require far more than lifestyle changes. It would require many of us to settle for something far less sparkly than the picket-fenced house of television suburbs. It would require those of us whose livelihoods are tied to the high-cost hubs to find new ways of getting by. (Whatever it is, it could not be nearly so easy as making a living complaining about how hard it is to make a living.) But most importantly, it would require thousands upon thousands of people to uproot themselves, to leave behind the places they and their families have always known—to leave behind their families themselves.

Subscribe Today Get daily emails in your inbox Email Address:

This is not a viable option for the vast majority of Americans, nor is it a conservative one. The pioneer way was an unpleasant necessity, and it should have passed into history once the continent was tamed. Real, functioning society is built on kinship networks and steady habits that cannot be sustained in a world where none but the privileged few are financially capable of putting down roots. Sure, everybody could move to Texas. But Texas and everywhere else would be a whole lot worse off for it.

The unpleasantness of our situation will become far clearer as the propertyless generations enter middle age. Perpetual rentership is already growing tiresome. Faced with the hard prospect of leaving behind their homes—their communities—for the chance of ownership, very few will take it. This will leave a highly educated, downwardly mobile critical mass of the thinking public bitterly resentful, concentrated in a few population centers, fat on bread and circuses but utterly without purpose. Add to all this the escalation of the culture war, the declines in religion and family life, the surrender of so much of this country and its wealth to invading third world hordes.

It is a fact borne out by every turn of history: The poor do not mount revolutions. The middle class, made to feel poor, do. Our own elites seem not to realize (or to care) how tiny the catalyst can be—a little slight here, a little pressure there, the faint but nagging memory that things were very different not so long ago.

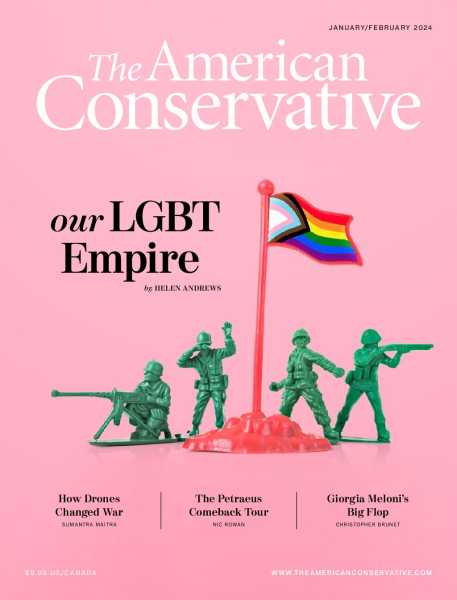

This article appears in the January/February 2024 issue

Subscribe Now

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com