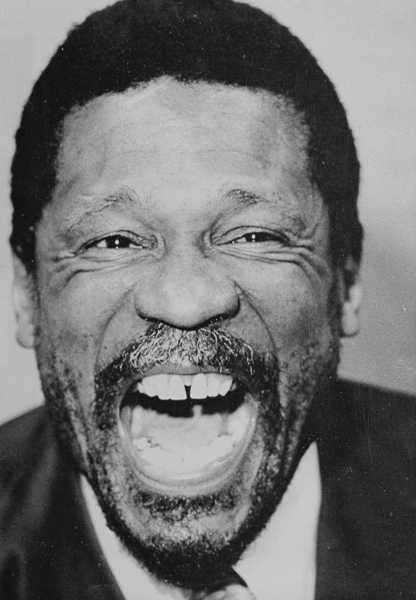

All of my thinking about Bill Russell, one of the greatest basketball players ever to live, who died on Sunday at the age of eighty-eight, begins with his face. He had a big smile, often employed, which seemed to flower outward from the endearing gap between his two front teeth. His brow was high and discerning. His cheeks—the real engines of his expressiveness—were flexible and squeezed themselves into soft folds. His eyes retained the devious innocence of a spirited child. In his maturity, he wore glasses and kept his hair and his irregular beard, both white, unbrushed. When he showed up at N.B.A. events, playing his role as resident legend and ambassador from the past, he always appeared to have ambled in on a whim.

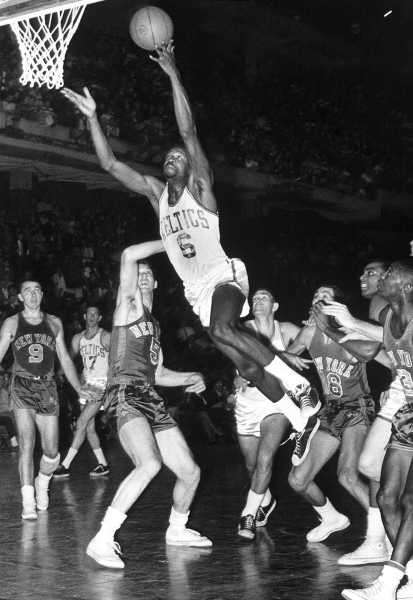

Russell shooting a layup against the New York Knicks.Photograph by Fred Kaplan / Getty

A time-out in the final moments of a playoff game with the 76ers.Photograph from Bettmann / Getty

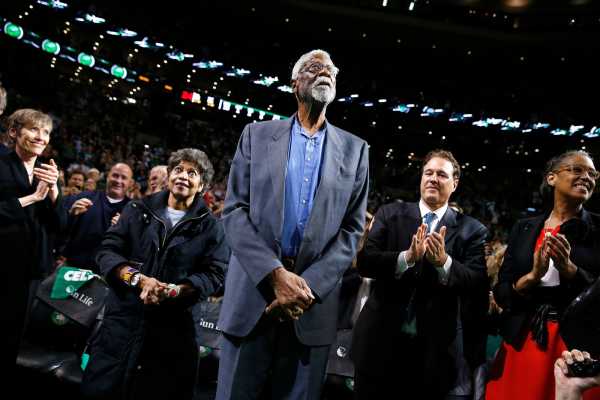

I guess I think of his looks—noble and insouciant, imposing and playful—because for most of my life, well after he retired as a player and a coach, Russell lent his physical presence to the basketball world as a constant symbol. He was often on hand after the deciding games of the N.B.A. Finals, handing such upstarts as Kobe Bryant, Dirk Nowitzki, LeBron James, and Kevin Durant the Finals M.V.P. trophy that, beginning in 2009, bore his name. Or he grinned from the crowd at games or award shows, sometimes—well, surprisingly often—flipping a quick middle finger at his friends.

Russell with Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.Photograph from Bettmann / Getty

One of the gifts of having been a basketball fan throughout the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first is that most of the still young professional game’s legends are alive or only fairly recently dead. Russell was one of the game’s great originary figures, its brightest early star, a kind of Adam and a kind of Paul Bunyan, his litany of accomplishments absurd in its length and fable-like texture. Many of his most far-fetched deeds were un-videotaped and therefore subject to the twin whims of memory and time. But he was also a contemporary figure, a bit younger than my own grandmother, still ramifying forward into the present. It was a lucky paradox, almost funny, for those of us whose lives overlapped with his. Imagine Sappho showing up to lecture at an M.F.A. program, or Plato in a hotel ballroom, at a convention of academic philosophers.

Russell, as head coach of the Seattle SuperSonics in 1977, talking to his team.Photograph by Mark Junge / Getty

Russell laughing, when the SuperSonics had qualified for the N.B.A. playoffs for the first time.Photograph from Bettmann / Getty

Russell’s gait was straighter, his hair darker, and his mien, at least in public, more consistently grave when, during the fifties and sixties, as a slim, graceful, brilliant center for the Boston Celtics, he unspooled a record of excellence unmatched in American organized sports. The details of his devastating genius sound fake: his teams won eleven N.B.A. championships in thirteen seasons, and he won five M.V.P. awards, in a time when that award was decided by a vote among the players themselves—his helpless rivals, undoubtedly bitter at his stinginess with victory, found his greatness impossible to ignore. He was an All-Star twelve times over and—sharing an era with another indomitable giant, Wilt Chamberlain—won the league’s rebounding title four times. (Russell is second in all-time rebounds, just a notch behind Chamberlain.) He played in ten win-or-go-home Game Sevens in the playoffs and won them all, and in those games he averaged slightly more than twenty-nine rebounds. As an undergraduate, he won the N.C.A.A. title twice, and the Olympic gold medal the one time he tried. (By all accounts, he could’ve been an Olympic high jumper, too.)

Russell with LeBron James in 2013, with James holding the N.B.A. Finals Most Valuable Player award named in Russell’s honor.Photograph by Lynne Sladky / AP

In an era when the N.B.A. was much less marketable, and therefore much less forcibly narrativized, than it is today, Russell nonetheless crafted a persona that lasted him a lifetime. Part of it was the intelligence and rectitude of his playing style. Over six-nine with long limbs and air-cutting speed, he offered his physical and mental gifts at the altar of defense. (He wasn’t known as a shooter, but he could’ve scored a lot if he’d made it a goal. One short video shows him on a fast break, zooming up-court, taking a few long steps that teleport him from half-court to the rim with an easy force that prefigures Giannis Antetokounmpo.) Game footage of Russell is rare, but what we do have reveals a greyhound’s grace and a brain like sonar, locating defenders who had slipped past his teammates and, in a loping step or two, arriving on time to offer assistance. A famous photograph depicts him jumping almost perfectly vertically, his arm outstretched like an ancient tree branch, blocking a shot that couldn’t possibly, given the distance, be his primary responsibility.

Such was the deep, self-giving morality of Russell’s game, and what made him a natural fit, in his latter years, to serve as a player-coach (not to mention the first Black head coach in any major American pro-sports league): he took every flinching movement or forward advance on the court as his own issue to address. The cost and the substance of his greatness was total awareness, an impossible density of movement and thought. He got so worked up before big games—knowing, surely, how unreasonable it was to do what he did—that, famously, he tended to throw up.

In a 1963 interview with Sports Illustrated, Russell talked about defense with a mind-spanning complexity that suggested how transparent the psychologies of other players were to him:

What I try to do on defense is to make the offensive man do not what he wants but what I want. If I’m back on defense and three guys are coming at me, I’ve got to do something to worry all three. First I must make them slow up or stop. Then I must force them to make a bad pass and take a bad shot and, finally, I must try to block the shot. Say the guy in the middle has the ball and I want the guy on the left to take the shot. I give the guy with the ball enough motion to make him stop. Then I step toward the man on the right, inviting a pass to the man on the left; but, at the same time, I’m ready to move, if not on my way, to the guy on the left.

Russell at a tribute in his honor during a 2013 Celtics game.Photograph by Michael Dwyer / AP

Concurrent with that on-court genius were his steadfast political engagement and personal resilience. The fifties and sixties were excruciating years in America, and they became a social gantlet for Russell. He was big, smart, self-accepting, sometimes remote, rightly pissed—the kind of Black man who flips switches in the wrong kinds of minds. (A similar mix of traits would later get Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, perhaps Russell’s worthiest successor, into the same sort of trouble.) Vandals in the Boston suburbs—quite possibly fans of the team for which Russell was a constant rain of nourishing manna—trespassed upon and destroyed his property, took shits on his bed, wrote “NIGGA” on the walls of his house. Hoover’s F.B.I. kept tabs on him. He kept playing, kept reading his books, kept showing up where it mattered. When he talked about his involvement with the civil-rights movement, he didn’t sound like a happy warrior or an eager activist—just a man who, by dint of his color and his status, had a job that he knew he couldn’t shirk. He loaned his presence, loaned that face and his voice, to help solve a problem he hadn’t caused. One more price to pay. It was help defense: if you could, you did. He saved no small measure of disdain for those who didn’t. “Some Negro athletes don’t show me much,” he told Sports Illustrated, in that 1963 interview. “I’m disappointed in them. They are politicians in the sense of saying the right things all the time.”

That he lived to be an uncontroversially beloved culture-hero—given the fires of those years, and given the pressures he so elegantly accepted—is one of history’s miracles, a dark but brightening irony that might have made him cough up one of his surprisingly high-pitched, cackling laughs. That he existed at all, a physical marvel, a diligent participant in struggle, is an even greater blessing. It’s worth celebrating. The N.B.A. should always hold an empty seat, somewhere near the floor, for Bill Russell. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com