It’s not often that a body of photography is hoisted up from obscurity and straight into the canon. When this happens, the images in question are often the work of a self-taught master, such as the compendious Arkansas portraitist Mike Disfarmer or the Chicago nanny and eagle-eyed street photographer Vivian Maier, both of whose œuvres had been left to molder until they were rescued by keen connoisseurs. But the work of Baldwin Lee, a graduate of M.I.T., where he studied with Minor White, and of Yale, where he studied with Walker Evans, has been hiding in plain sight. Selections from his archive of nearly ten thousand pictures, taken in poor Black communities in the American South between 1983 and 1989, have been exhibited sporadically. “I showed enough to get tenure and raises,” he told me recently, from his home near the University of Tennessee, where he has been teaching for four decades. But a new book from Hunters Point Press—the first-ever collection of Lee’s work—and a solo exhibition at New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery make the case that he is one of the great overlooked luminaries of American picture-making.

Lee was never meant to be a photographer. Born and raised in New York, he was the eldest son of a reluctant Chinatown “noodle king,” who had emigrated from Hong Kong, fought in the U.S. Army on D Day, and had his aspirations to become an architect dashed when he inherited his uncle’s thriving business supplying noodles to Chinese restaurants up and down the East Coast. Chinatown at the time was an insular, conservative environment, which Lee described as “essentially a small-town upbringing.” He recalls that, of the six hundred students in his elementary and middle schools, only two were non-Chinese. From childhood, Lee was given the impression that he had but one goal: to attend the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which would lead him, his father hoped, to a practical, respectable, high-paying job. Academically gifted and singularly focussed, Lee made good. He graduated as class valedictorian from Brooklyn Tech, with an M.I.T. admission letter in hand. Then he showed up in Cambridge and promptly hit a wall.

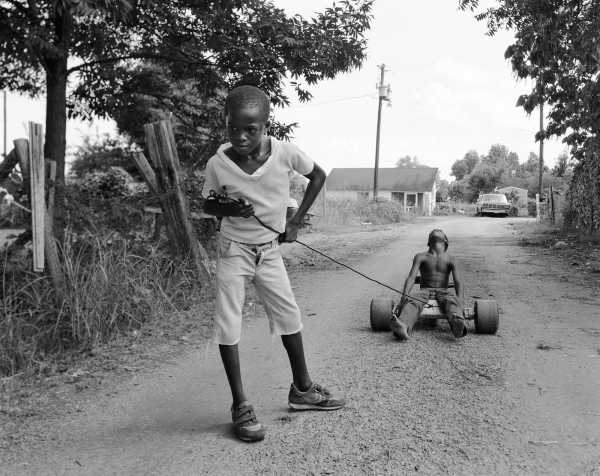

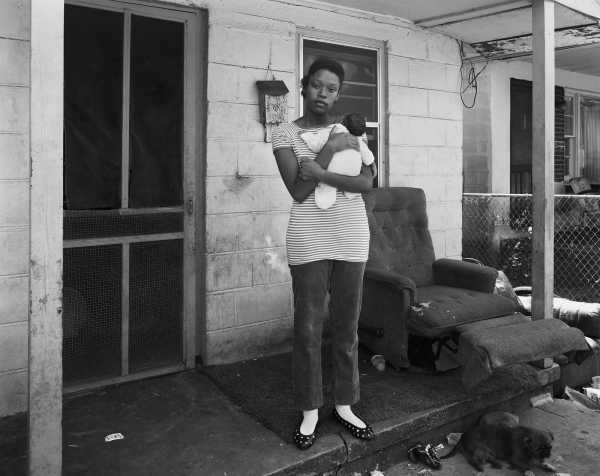

Vicksburg, Mississippi (1984).

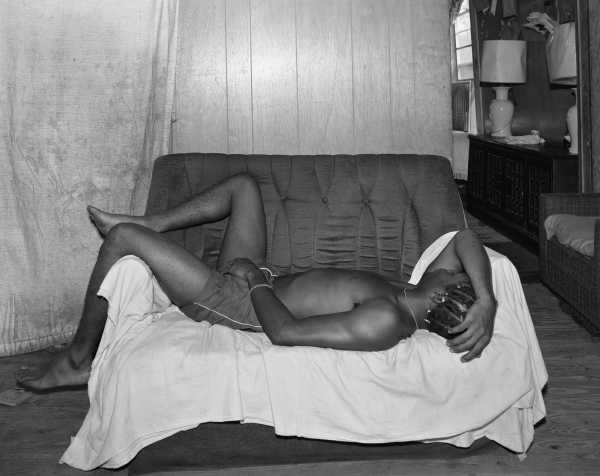

Montgomery, Alabama (1984).

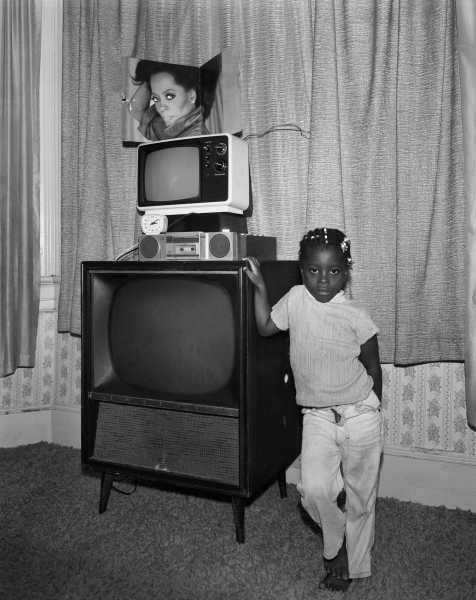

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

“It was the worst,” Lee recalled, adding, “I was just despondent, until I took my first class with Minor White.” Lee recounts his first encounter with the photographer, in his sophomore year, as some people might narrate their run-in with an ambassador from another planet. “There was this man who was pale, very, very pale, and he had a shock of uncombed white hair, and walked into the room barefoot. I go, Wait a minute, where am I? And when he began to speak, I was really stunned.” It wasn’t even what White’s had to say about photography that made an impression. “He talked about Eastern mysticism. He talked about spiritualism. He talked about peyote. He was the first gay person I ever met.” Lee would take classes with White for the rest of his tenure at M.I.T., including a hilariously anachronistic course called “The Creative Audience,” for which White gathered students in a darkened lecture hall and had them interpret abstract photographs by expressively massaging each other to exotic soundtracks of gamelan bells or Gregorian chants. Lee was hooked, but his father was less than pleased. When, on the drive home from graduation, Lee announced that he planned to become a photographer, he noticed a single tear roll down his father’s cheek. Just a few months later, his father died in an accident.

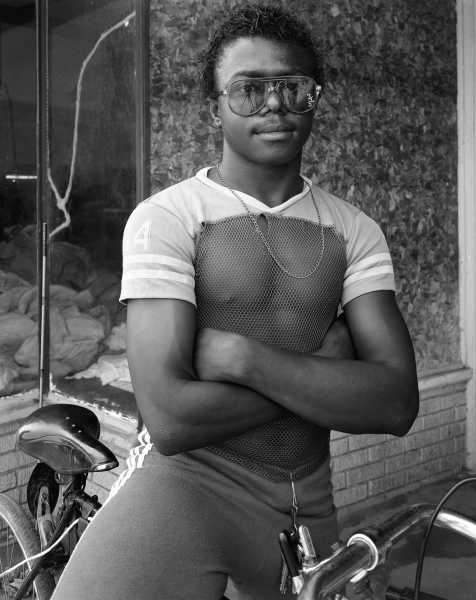

Shreveport, Louisiana (1986).

The next year, 1973, as a student at the Yale School of Art’s revered photography program, Lee landed a job as Walker Evans’s personal printer in his home darkroom, in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Where White had introduced Lee to the life of a bohemian, Evans was a model of the artist as aristocrat. “I mean, he dressed impeccably, and he spoke with a kind of patrician accent,” Lee recalled. “He wore tweed clothes from J. Press. He wore English Peal & Company shoes. He was a bon vivant.” Evans, who died in 1975, would be a lasting influence for Lee—while on the road making pictures in the nineteen-eighties, Lee would take along a book of Evans’s photographs—but at Yale Lee struggled to find his perspective as an artist. He recalled that his final project in graduate school, a collection of urban landscapes and architectural photographs, had been pronounced “dead” by Irving Penn. Later, when Lee stayed on at Yale to teach, Garry Winograd said that Lee “didn’t know what he was talking about.” “I’ve been insulted by the Mount Rushmore of photography,” Lee told me, with pride. Part of the problem was his crippling shyness, which, in 1981, he sought to overcome by giving himself an assignment that he still uses on students to this day: walk up to strangers and ask to take their picture. “It led to a year of misery,” he recalled. “And, of course, the pictures all sucked.” But it worked: “I turned myself from a wallflower into a monster.”

Charleston, South Carolina (1984).

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

This hard-won transformation coincided with Lee taking a job at the University of Tennessee. The first chance that he got, he took his four-by-five-inch view camera on a road trip. “I had no agenda, no plan.” he told me. “I took pictures of everything: landscapes, architecture, closeups, still-lifes, pictures at night, people, old, young, white, Black, poor, rich. I just wanted to see.” What followed was an accidental political awakening. “I never really thought much about race. But one thing that I have always been defined by is that I have an absolute repulsion to injustice and unfairness. And so, when I did this first trip in the South, when I was interacting with Black Americans, something happened. And this wasn’t anything that I would have ever conceived of occurring. But all of a sudden, in the course of ten days, I became a political person. I found my reason.”

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

Over the following years, Lee crisscrossed the South documenting Black communities, usually travelling for a week or two at a time. His trick to orient himself in new towns was to stop by the local police station with a map and ask the officers to circle neighborhoods that he should avoid. Then he’d head straight there. The portraits that he made are distinguished by their uncommon personality and grace. An image from 1984 shows a man in Lakeland, Florida, taking a break from his work sifting through the still-smoldering rubble of a house levelled by fire, his eyes turned imploringly heavenward, like the figure in Giovanni Bellini’s “St. Francis in the Desert.” In a photo taken in 1986, a man standing on a unremarkable street corner in Tutwiler, Mississippi, wears tattered clothes and grubby Chuck Taylors—but, with his aviator shades on and one hand thrown balletically in the air, he looks ready to run the dance floor or walk the runway. In other photographs, moments of joy and play break through ramshackle surroundings: a couple kiss in a dingy doorway; a kid pulls his shirtless and shoeless friend along on a cart, down a dirt driveway, his head thrown back; an older man tenderly examines a flower in his garden.

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

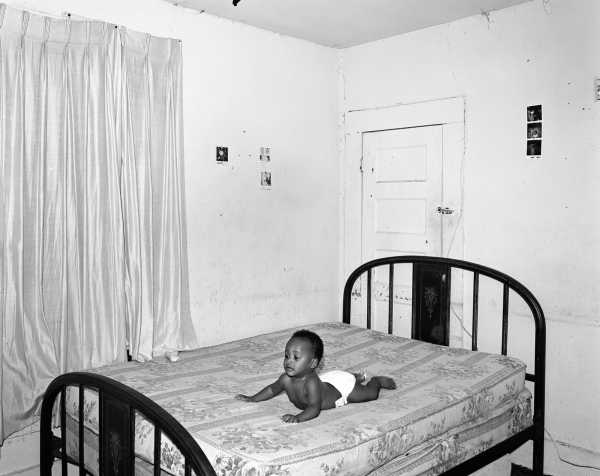

The resulting pictures have an agenda, of course, but they rarely make it explicit. “I may have been there for these reasons of moral outrage, but, when you start to make a picture, that has to be pushed aside,” Lee told me. “If you try to make it be about some sort of ideological or conceptual thing, it’s going to be a stupid picture.” One notable exception, in my mind, is a picture from 1985 of a Black man sweeping the sidewalk in front of an Arkansas courthouse, which is emblazoned with the Orwellian phrase “Obedience to the Law Is Liberty.” In terms of sheer didactic heft, the photograph matches Gordon Parks’s blisteringly ironic 1942 nod to Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” for which he posed the custodian Ella Watson, mop and broom in hand, in front of an American flag hung in the Washington, D.C., building where she worked. Equally shocking are a pair of interiors that Lee shot—one in Valdosta, Georgia, in 1985, the other in Natchez, Mississippi, the year prior—which are nearly indistinguishable from Depression-era pictures that Evans took. They function as both a homage to Lee’s teacher and a grim testament to the persistently meagre fruits of American progress.

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

Lee recalled feeling surprised that, despite his Asian heritage, his older Black subjects would often automatically code him as white, and treat him with a kind of “hierarchical obsequiousness,” until he was able to establish a more natural rapport. He is fond of recounting that if he asked twenty people to pose for a photograph, nineteen would say yes. Perhaps unsurprisingly, white residents of the towns that Lee visited were less confused about his place in the racial pecking order. He was frequently viewed with hostility, he recalled, and was on at least one occasion threatened with a gun.

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

Untitled (ca. mid 1980s).

Lee made his magnum opus in the course of six years. Then, in the mid-nineties, he stopped making pictures entirely. Outside of teaching, he has not picked up a camera since. In our era of fervid careerism and content creation, this seems almost like a form of madness. Lee told me that his decision was guided, in part, by a pet theory that most artists do their greatest work over a period of about seven years, and then plod diminished through the rest of their careers. By quitting while he was ahead, Lee reasoned, he saved himself the inevitable indignity. But the work also weighed on him. There was the stress of the road, the long stretches away from home and his wife, whom he had met while teaching at the Massachusetts College of Art in the early nineteen-eighties. But there was also a feeling that, no matter how righteous his intent, no matter how sensitive his photographs, there was an unbridgeable gap between him and his subjects. He’d spend the day photographing people living in seemingly inescapable poverty, and then he’d return, at night, to a hotel. “You know, hot shower and meal,” he said. “The incongruity of it was just hard to do.” He recalled that a couple once pulled him off the street, to take a picture at a wake for their child, who had died after falling off of their bed and getting tangled in the sheets. They hadn’t been able to afford a crib. Earlier the same week, Lee and his wife had been shopping for cribs for their first child, who was born in 1988, and lamenting that the antique ones they coveted did not meet accepted safety standards.

One last-straw moment came when Lee was driving in rural Georgia and noticed a one-armed man awkwardly pushing a lawnmower. Lee pulled his car over to get the shot. “There’s a lot to say that is good about ambition,” he said. “But then it can blind you, too. I was so excited to make that picture. Then I thought about it for a second, as I was getting out of the car. I stopped. I slipped back onto the seat, closed the door, and I turned around. I drove home. I just drove the five hundred miles to come home, because I was so ashamed of myself.” Walker Evans famously exhorted those who would follow in his footsteps: “Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something.” But, ever the aloof patrician, Evans seemed unbothered by what he was staring at. Lee went searching for the injustices at the core of American life. He found beauty but also horror. Eventually, he decided to look away.

Nashville, Tennessee (1983).

Sourse: newyorker.com