Thomas Mann has come home to 1550 San Remo Drive, in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles. Editions of Shakespeare, Schiller, Dostoyevsky, and Flaubert rest on the shelves of Mann’s study, which looks out past a stand of eucalyptus trees to the Pacific Ocean. German is again spoken in the corridors of the home, which the émigré architect J. R. Davidson designed to Mann’s specifications, and which the author occupied from 1942 to 1952. The questions that Mann pondered during his California exile—What is the future of democracy? Can the civilized world hold back the forces of irrationalism?—are very much in the air. On Monday, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the President of Germany, inaugurated the Mann house as a residence for visiting German scholars, scientists, and artists. Alluding to the white-walled exterior of the building, Steinmeier said, “Tonight, ladies and gentlemen, the attention of our transatlantic community is on a different White House.” He called Mann’s study “the Oval Office of the émigré opposition to Hitler’s reign of terror in Berlin.”

When, in 2016, the Mann house went on the market, it was feared that a buyer would tear it down. The German Foreign Office, of which Steinmeier was then the head, made the extraordinary decision to buy the property, for more than thirteen million dollars. The house has been linked to an extant residency program at the Villa Aurora, the former home of the novelist Lion Feuchtwanger. News of the sale arrived not long after the 2016 election, and seemed symbolic of the changing fortunes of democracy in Germany and America. As in the nineteen-thirties, democracy’s future is uncertain, but as of this writing Germany looks to be a more secure haven for the system of government that Mann equated with truth, freedom, justice, and “inviolable human dignity.”

The renovation project moved along quickly, despite the usual complications. Termite issues arose; permits were slow in coming; neighbors raised concerns about noise. Last fall, I visited the work in progress. Steven Lavine, the former president of CalArts, who serves as the founding director of the Thomas Mann House in Los Angeles, gave me a tour. The challenge was to update the building while maintaining its original ambience. From the outside, it is strikingly contemporary in appearance. Sleek, unostentatious, quietly eccentric in its oblong plan, it comes across as a considered response to modernist aesthetics—not unlike Mann’s own later work.

The worries of the neighbors appear to have subsided, as it becomes clear that the house will not be a “Magic Mountain” party pad. A number of local residents were invited to the inaugural ceremony, and Steinmeier addressed them directly: “As President of Germany, I officially apologize for the construction noise.”

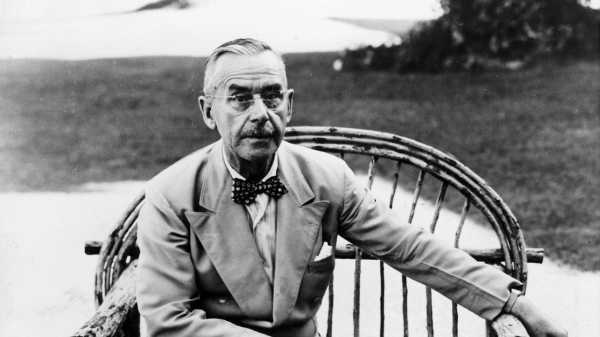

Mann occupied the house at 1550 San Remo Drive, in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles, from 1942 to 1952.

Photograph by Meißner / Ullstein Bild / Getty

Standing to one side as Steinmeier spoke was an elderly gentleman with arching eyebrows, a jutting nose, and pinpoint eyes—a distinctly Mann-like figure. This was the psychologist and author Frido Mann, Thomas’s seventy-seven-year-old grandson. He spent time at the house as a child and often went for long walks with his grandfather. In the living room where Mann had once listened to his Wagner records, I asked Frido about “Doctor Faustus”—Mann’s wartime novel of genius and madness, in which Frido serves as the model for an angelic, doomed boy named Nepomuk Schneidewein. Frido told me that he had felt a strange kind of scrutiny in gatherings on San Remo Drive: “I just saw these people watching me—‘There he is, the boy.’ ” To be rendered into fiction by Thomas Mann was an unnerving experience. Frido, like most other members of his family, has long struggled to come to terms with his grandfather’s devouring shadow.

A small army of German media attended the ceremony: there were as many TV cameramen and reporters as there were cater-waiters. The American media was largely absent—a symptom of disparate priorities, no doubt. In the mid and late twentieth century, Mann was widely read in America; “Death in Venice” was a fixture of the syllabus. But, as the scholar Hans Rudolf Vaget has observed, Mann is no longer a common point of reference in American literary circles, even as his reputation in Germany has steadily ascended. At the Mann house, two younger Americans standing next to me were uncertain about who was being celebrated. One asked, “So, is Thomas Mann the architect?” I tried to explain briefly who Mann was, and recommended “Mario and the Magician,” his 1929 tale of a fascistic hypnotist manipulating a crowd.

In a speech the following day, at the Getty Center, Steinmeier gave good reasons for revisiting Mann’s writing. It was pleasantly jarring to hear a head of state speaking in an intellectual register, alluding not only to Mann but also to Kant, Whitman, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Steinmeier ably sketched Mann’s political meanderings, from strident nationalism to an embrace of democracy during the Weimar Republic era. Steinmeier went on: “It seems to have been only in the United States that Thomas Mann changed from a democrat-by-reason into a democrat-in-heart. And all his enthusiasm was focussed on a single person: Franklin Roosevelt. Frido Mann, you gave us such a wonderfully vivid description of some of your childhood memories—how, at the breakfast table in San Remo Drive, your grandfather spoke with flashing eyes and great, dramatic gestures of the charismatic yet physically depleted President.” After Roosevelt’s death, though, the atmosphere began to change:

Only a few years lay between Roosevelt’s shining example and the

descent into a toxic political climate of intolerance and

polarization, prejudices and conspiracy theories, and the state-led

erosion of fundamental rights and an independent judiciary. While the

Marshall Plan was enabling the ruined Germany to start afresh,

economically and morally, in California Thomas Mann found his friends,

exiles, artists, intellectuals, his own children Erika, Klaus, and

Golo, and eventually himself the target of McCarthy’s

zealous Communist hunters. Under the heading “Dupes and Fellow

Travelers,” Life magazine counted him

among the illustrious ranks of suspects ranging from Charlie Chaplin

and Leonard Bernstein to Arthur Miller and Albert Einstein.

And so Mann went into exile once again, in Switzerland. Yet, as Steinmeier pointed out—and as Vaget emphasizes in his book “Thomas Mann, der Amerikaner”—Mann died an American citizen. He never renounced the Roosevelt dream.

Everyone was waiting for Steinmeier to mention Trump, who was spreading lies about German crime statistics on Twitter that very morning. But the Bundespräsident declined to score easy points. “I would like to remind all those in Germany who are currently shaking their heads in disgust every day over the end of U.S. democracy, and even doing so with a certain cultural arrogance, of Thomas Mann’s crystal-clear words: ‘No, America needs no instruction in the things that concern democracy.’ No other democracy in the world has proved to be as resilient and renewable as that of the United States.” Steinmeier named some current “forces of renewal”: “The students no longer prepared to accept rampant gun violence, the dedicated people breathing new life into Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign, the countless women standing for political office around the country in greater numbers than ever before.”

Steinmeier’s culminating point was that democracy has no safe home, that the fight for it is unending. As Mann said in 1938, it should “put aside the habit of taking itself for granted, of self-forgetfulness”; instead, it should use its newfound fragility as a spur to action. Steinmeier sees the Thomas Mann House as a site on which debates over the democratic future can unfold. A conference at the Getty Center gave a foretaste of what he had in mind: Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, an immigration expert at U.C.L.A., and the German social scientist Jutta Allmendinger, one of the first wave of Thomas Mann fellows, traded statistics on immigration in Germany and the U.S., suggesting that the underlying aspirations and fears are closer than they might appear.

One of Mann’s great insights was that a civilization decays from within. Its enemies are always shadows cast on walls. He understood as well as anyone the deep, twisted cultural roots of the Nazi catastrophe: that is what “Doctor Faustus” is about, in part. He died without a homeland—a German exile turned American exile. So it is a powerful thing to see light streaming from the study he loved, figures silhouetted in the windows. Thomas Mann is buried in Zurich, but his spirit is abroad.

Sourse: newyorker.com