Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The first zine that I ever read was called Snotrag, and its author was a straight-edge hardcore fan, bike enthusiast, and occasional raver who lived in Vermont. I was none of these things; our main commonality was that we were both at debate camp. Snotrag was just five photocopied pages folded in half, but having it handed to me felt like an intimate gesture. Each page was filled with wobbly, hand-arranged columns of riffs, interviews, reviews of basement shows and seven-inch singles, and recaps of debate rounds, with little graphic design beyond the occasional boldface album title and a photocopied ACT UP sticker. There were two pages left completely blank, presumably by accident. I recall a feeling of discovery, not just of new musical genres or bands but of the fact that you could be into so many different things at once: punk, Derrida, nanotechnology, AIDS activism, Islam, the great outdoors. I was inspired to start my own zine as a way to test out different poses, to figure out whether I was a dreamer or a cynic, a zealot or a snob, though my sense of taste was less confident. I mostly cultivated a political stance out of everything I rejected. Figuring out what I actually loved would come much later.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was participating in a long tradition shared by the young and alienated, people who were enamored with the fringes of culture. It would be impossible to imagine a comprehensive history of zines, since it would be made up of so many small, forgotten moments like this one. Countless publications have started and then never made it past one or two issues. What mattered was that you tried at all. And what’s drawn people to trying is less a clear lineage than a shared feeling.

Many believe that zines date back to the nineteen-thirties and forties, when science-fiction enthusiasts eager to dissect their favorite stories (or publish their own) began making “fan magazines,” or fanzines. These early examples, some of which involved teen-agers running amok with typewriters and school ditto machines, were an expression of devotion—self-published, amateurish, and unconcerned with the bottom line. They were also a defense against loneliness. Starting your own publication always suggests a desire for connection and community, casting about for fellow-oddballs, willing a readership into existence. Throughout the twentieth century, zines were as much about what people loved as fans—comic books, horror films, rock music—as what they rejected. In the nineteen-seventies, with the popularization of xerographic copiers, the form became closely associated with the punk subculture and its do-it-yourself ethos. In the decades that followed, zines became an important forum for the discussion of radical feminism and identity, avant-garde poetry and art, the chosen platform for the thoughtful and angst-ridden. Pigeons of New York, weird Wikipedia entries, graffiti, Chinese food, dumpster diving, anarchist politics: there’s probably a zine for any niche interest that you can imagine.

“Copy Machine Manifestos,” an ambitious exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, curated by the art historians Branden W. Joseph and Drew Sawyer, documents a sliver of this world. It focusses largely on artists’ zines, loosely defined as those published by people with some relationship to the art world. The Canadian artist and pioneering zine-maker A. A. Bronson has characterized such works as “format-oriented,” as artists, disenchanted with the snooty circuits of galleries and critics, explored the possibilities of do-it-yourself publishing.

Thousands of zines are on display in “Copy Machine Manifestos,” and it offers a thrilling survey of North American subcultures throughout the twentieth century. The artist John Dowd recognized the possibilities of the Xerox machine early on, and in the late nineteen-sixties he began circulating stark, black-and-white publications, among them Fanzini and The Star, which featured Dada-inspired collages of rock stars, Disney icons, and advertisements. At a time when it was still onerous to collect and manipulate printed images, there was a subversive power to Dowd’s cut-and-paste juxtapositions. “I really like pictures in sequence,” he would later say, “facing each other on opposite pages; then you can say something.” Dowd was part of the mail-art scene, which circumvented traditional media and distribution channels in favor of artists trading pieces through the postal service. His zines spawned their own fan club and inspired others to luxuriate in the grainy, washed-out aesthetics of xeroxing.

Art work by Anna Banana, “Vile, vol. 1, no. 2 vol. 2, no. 1 (issue 4)” / Photograph by David Vu / Courtesy Brooklyn Museum

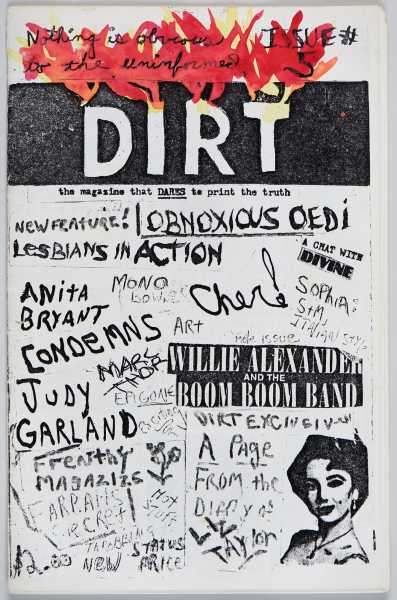

Whereas the counterculture of the sixties resulted in a boom in community and movement newspapers, the artists’ zines of the nineteen-seventies pushed toward more transgressive extremes. Vile was a San Francisco publication that emerged in the mid-seventies, inspired by a Toronto one called File; both appropriated the red-and-white logo from Life magazine. The covers of Vile were clearly meant to shock; one depicts a hanged man with an erect penis. Issues of Dirt, an early Boston zine by Mark Morrisroe and Lynelle White, feature interviews with punk musicians alongside hand-scrawled headlines lampooning the celebrity-obsessed gossip of mainstream tabloids. Despite the maverick bent of D.I.Y. publishing, zines still carried traces of the mass-culture moments that they were trying to resist.

The Brooklyn Museum show is staged chronologically, and, by the time the exhibit reaches the eighties, the movements and subcultures represented by these zines feel nameable and bounded, from the emergence of a queer-zine underground in that decade to the rise of Riot Grrl in the next. One of the most moving pieces on display is not an issue of a zine but “Envelope Quilt,” by the artist and filmmaker K8 Hardy, which stitches together the envelopes mailed to her by readers over the years.

The cultural historian Stephen Duncombe, in his 1997 book “Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture,” described zines as “bursts of raw emotion” that prize “unfettered, authentic expression” over polish. “Envelope Quilt,” which bridges the distance between the artist and her readers, captures some of that energy. But the museum’s focus on so-called artists’ zines means that “Copy Machine Manifestos” is less interested in random, amateurish provocations and more invested in the relationship between self-published works and the canons and conventions of art history. Displaying stapled photocopies meant to be subterranean and anti-institutional behind glass, in a museum, will always feel a bit strange, particularly when the original appeal of zines was both their tactility and their disposability. The exhibit ends up feeling like a startling collection of covers, with only a teasing sense of what was written inside. Contextualizing works within artists’ œuvres would have helped, too. What did the expanse of a zine allow Raymond Pettibon, Miranda July, or Harmony Korine to explore that they couldn’t in their painting, or writing, or filmmaking?

The last gallery featured a small display of zines for picking up and browsing, and a gallery online featured scans of selected issues. But there were so many more, encased in glass, that I had wanted to open—to see whether they were typeset or handwritten or had a sense of humor, what kinds of things they reviewed or railed against. I was reminded of a wonderful 2010 show about the history of New York’s alternative art spaces, at the now shuttered Exit Art, a key part of that world. Each space was represented by a box of archival materials, arranged on a massive table, with gloves and magnifying glasses provided for patrons. We were invited to scrutinize reproductions of the paperwork, ephemera, and publications of these spaces ourselves—to feel a small part of the communities they each sought to convene.

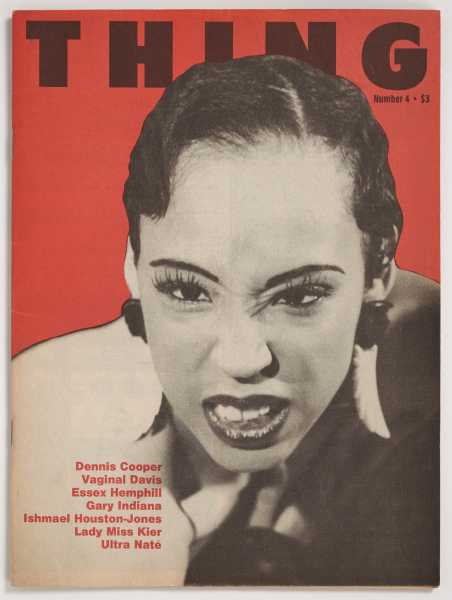

Art work by Robert Ford / Photograph by Evan McKnight / Courtesy Brooklyn Museum

An excellent companion book, published by Phaidon and edited by the show’s curators Joseph and Sawyer, makes up for some of the exhibition’s inherent limitations, reprinting full pages from many of the zines in the collection, and giving readers a fuller sense of what these artists were resisting. Some offerings feel modest and intimate, thickets of handwritten notes and remixed clip art. There are riffs on coloring books, advice columns, corporate advertising. Ari Marcopoulos’s nineties and two-thousands zines, full of grainy Xeroxes of his photography, feel like a rejection of digital perfectionism, instead capturing the thrumming chaos of the everyday. Others suggest aspiration, maybe even a desire to become a real magazine; Thing, the Robert Ford-helmed zine about Black, queer club culture from the nineties, feels like a scaled-down analogue to mainstream life-style publishing, with clean, sophisticated layouts and graphic design.

Mostly, the book’s essays shift attention away from the artists and publishers, conveying a sense of the excitement felt by readers who learned that a different world was possible. The art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson shares memories of the “cool older sibling” effect of coming across a stranger’s zine—a treasure, though one not meant to be treated with too much curatorial preciousness. Instead, she’s drawn to the informal circuits that emerge when zines circulate as intended, as “knowledge is passed down and also passed around.” The critic Tavia Nyong’o tenderly recalls how reading old copies of Idle Sheet, a New York zine documenting the ballroom scene, was like seeing “hieroglyphs of my future.”

The thrill that Nyong’o describes was neither a common, everyday sensation of the mid-nineteen-nineties nor one that was particularly rare. It just required effort and luck. I came into the world of zines around this time, when the rise (and marketability) of alternative culture meant that they were no longer the sole province of remote weirdos. Publishing zines was a normal, almost generic thing to do if you had poetry to share, some semester-abroad escapades you wanted to jot down, a new band you loved. Sometimes it seemed like there were things that my friends and I could communicate to one another only by trading zines. Making mine insured a ready-made excuse to contact strangers with silly questions that I was trying to figure out about myself. I learned a lot about taste, mostly through mimicking what I read in Giant Robot, Secret Asian Man, Trash Heap, or Chickfactor, and, because of my adoration for some Halifax pop bands of the early nineteen-nineties, I befriended a disproportionate number of people from eastern Canada. There were moments of kinship and community, and there were times when it seemed like the most embittered individuals on the planet were zine-makers reviewing other people’s efforts.

It was impossible not to think about these memories as I walked through “Copy Machine Manifestos.” I didn’t recognize many of the titles; nothing I was involved with when I was younger would have been deemed important by the museum’s standards. But I was reacquainted with the random joy of coming across something new and trying to figure out my relationship to it. Before it was possible to connect with strangers around the world instantaneously, they would sometimes appear erratically, intermittently, and mysteriously, in print. You’d recognize a fellow-traveller, even if you were heading for different horizons.

Perhaps this is why a lot of young people are returning to a seemingly outdated form of self-expression; it seems that there are more how-to workshops and zine fairs than ever before. These efforts exist in a space that’s out of the Internet’s reach. Any one of us has access to a global megaphone. But maybe what we seek are smaller, out-of-the-way conversations, forms befitting minor histories. Zines still provide what Bryan-Wilson terms a “tender and protective intimacy.” They allow us to feel like we are still sketching the outlines of our true selves. They are work, but not an onerous amount, just enough to make the endeavor seem a path of slight resistance. That friction—between doing something yourself and choosing to do nothing—is where politics emerges.

I still keep Snotrag on my desk, along with a few other zines that retain a sense of mystery for me. I don’t know whether there were any other issues, and I’ve never listened to any of the bands interviewed inside. But I read the editor’s note over and over. “BELIEVE IN YOURSELF, REMEMBER YOUR FREINDS [sic], BUT DO NOT DELUDE YOURSELF, BE BOLD ENOUGH TO TRUST SOMEONE, REACH OUT YOUR HAND TO SOMEONE WHO NEEDS IT.” ♦

Art work by Mark Morrisroe and Lynelle White / Courtesy Brooklyn Museum

Sourse: newyorker.com