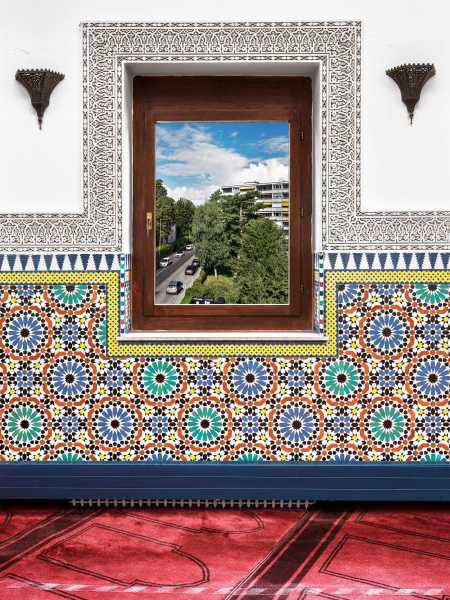

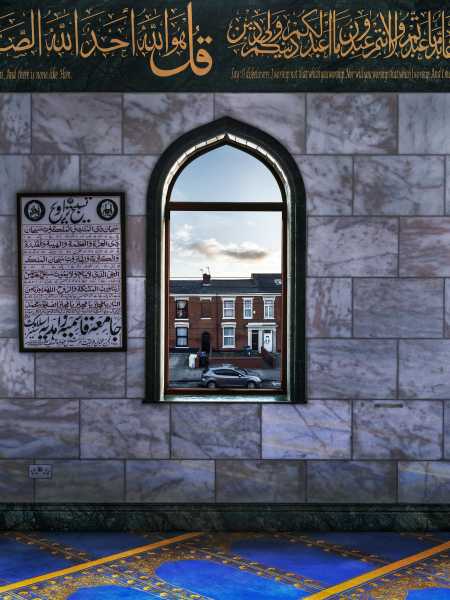

Marwan Bassiouni’s photographs in “New Western Views” capture two places at once. Each picture in the series was taken inside a mosque, with the camera pointing toward the windows to reveal the buildings or landscapes beyond. But the pictures give equal weight to the interiors of the mosques themselves, which might be colorful or muted, ornate or spare. Bassiouni began the series in the Netherlands, in 2018, touring the country to visit some seventy mosques while attending art school in the Hague. (A book of those images, “New Dutch Views,” was published in 2019.) Two years ago, he expanded his travels to the United Kingdom and Switzerland. Bassiouni told me recently that he sees the project as an act of portraiture. “I’m photographing spaces that, in a way, have a soul,” he said.

Bassiouni was born in Switzerland, in 1985, to an Egyptian father and an American mother. The nearest mosque was about thirty minutes away, in Geneva—he visited twice a year during Eid and for the occasional Friday prayers. He was not a practicing Muslim until the age of twenty-four, around the time that his interest in photography began. He was working in a restaurant at a ski resort, in the Swiss Alps, and living on its premises. Left alone each evening at the top of the mountain after the other employees left, he began photographing the view with his three-megapixel phone camera. Later, he assisted a commercial photographer on fashion shoots, and then worked as a documentary filmmaker for a human-rights organization focussed on the Middle East, a gig that coincided with the Arab Spring. In making photographs that simultaneously depict both the inside of mosques and their outside environments, he was interested in engaging with popular perceptions of Islam. In the easily suggestible Western imagination, the mosque has often been cast as a site of sinister machinations. Bassiouni’s images offer an alternative gaze from within, with the windows of the prayer rooms providing an unfamiliar framing for ordinary sights: a row of suburban houses; the parking lot of a supermarket, flanked by a red bus in London; looming apartment towers; a sports pitch; a highway; a church.

Bassiouni’s approach is informed by the aesthetic values of Islamic art, such as the importance ascribed to geometry, and the notion of euphony with regard to the poetics of the Quran. Every photograph is made with natural lighting and with two exposures, one for the inside and one for the outside space. The images are then combined digitally to produce a scene that corresponds as closely as possible to what appears in reality. “From the Islamic perspective, you’re trying to respect the way things are created,” he said. “So you wouldn’t want to change things, and you wouldn’t be able to do it better. There’s a natural balance and harmony.” Some of the images bring to mind the precision of Indo-Persian miniature paintings, in which elaborate scenes are encased within intricate borders.

Elsewhere, the interior spaces are palimpsests, bearing the quiet traces of previous tenants. In the United Kingdom, Bassiouni has photographed mosques that were formerly cinemas, churches, pubs, night clubs, gentlemen’s clubs, working men’s clubs—their floors now replaced with plush carpets in sapphire or crimson, walls adorned with minarets and Quranic verses. Clues of these past lives are mostly long buried, but occasionally one can identify an old radiator or wood panelling. A wall painted in lime green evokes the possibility of psychedelic forebears.

To view the photographs is to be engulfed in these mysteries. For exhibitions the images are presented at large scale to approximate the experience of being inside the spaces peering out, allowing viewers to imagine that they, too, are standing among the congregants in the room. Ultimately, Bassiouni hopes that audiences will forget that they are looking at a photo. Perhaps they might also forget that there is a separation between the two elements of each photograph, and see that the mosque is as much a part of the landscape as the church or grocery store it looks out on, enmeshed in the mélange of the architecture beyond and the lives that are led there. Bassiouni recalled a recent visit to a mosque in the Swiss canton of Valais at sunset, during the Maghrib prayer. The space was housed in a multipurpose industrial building, whose other rooms were rented out to various businesses. As the prayer concluded, the sound of upbeat music could be distantly heard. In another room, an aerobics class was beginning.

Sourse: newyorker.com