Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In a short story that serves as the preface to “Dream About Nothing,” Bobby Doherty’s new book of photographs, the writer Lauren Cook narrates the thoughts of a protagonist who, on waking each day, is struck anew with a form of amnesia. “Every morning I open my eyes and see my room for the first time,” Cook writes. “The hardwood floor, my white duvet. The birds on the fire escape, the potted plants. They’re amazing and they’re all mine and I can barely believe it, that I’m here with them.” The amnesiac’s recursive sense of wonder can help us think about the images in “Dream About Nothing.” Doherty is a commercial, editorial, and art photographer, and, across these genres, his pictures often feature mundane, everyday objects and figures. And yet, through his lens, these are remade, calling forth a metaphorical awakening—the heat and flash of the new. To look at Doherty’s photographs is to think, Was all of this really around us the whole time?

Doherty, who is in his mid-thirties, and grew up in Putnam County, New York, began taking photos as a child, after his grandfather gave him a point-and-shoot film camera when he was seven. (“He was a photographer, but also a bodybuilder and an actor,” Doherty told me when we spoke on the phone recently. “A real character.”) Doherty approached photography very seriously from the start. “I was a little investigator with my little camera. I was, like, I’m going to walk around the woods and photograph trash, go through the closets in our house and photograph the Christmas ornaments,” he said. As a teen, he continued to take pictures voraciously, looking for meaning in the objects around him. “I’d take photos in nature, on the street, but also still lifes in my bedroom, where I’d arrange fruit and weird little porcelain figurines on a little IKEA table.”

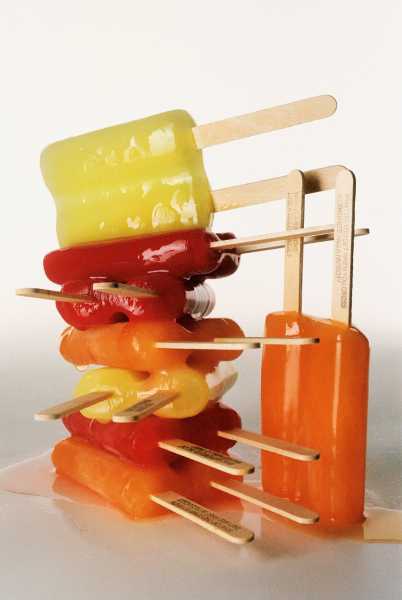

After attending the School of Visual Arts in New York, Doherty established himself as a successful commercial and editorial photographer, shooting hyper-glossy, ultra-colorful studio images of whimsically arranged accessories, food items, and beauty products for publications like New York, W, and the New York Times Magazine, and brands like Zara, Collina Strada, and Ghia. “Immediate legibility is a big part of my photography,” Doherty said. But the pictures also reward a further glance: “When you linger for a bit longer, how you think you understand them starts to fall apart.” Much like Irving Penn, by whom he is deeply influenced, Doherty is interested in making gorgeous images—“I can’t stand when a picture isn’t beautiful,” he told me—but he also wants to pull the rug out from under the viewer, revealing something tarnished or a bit off about what he trains his eye on.

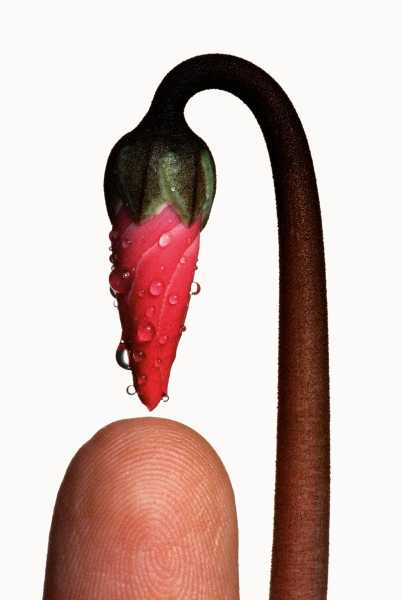

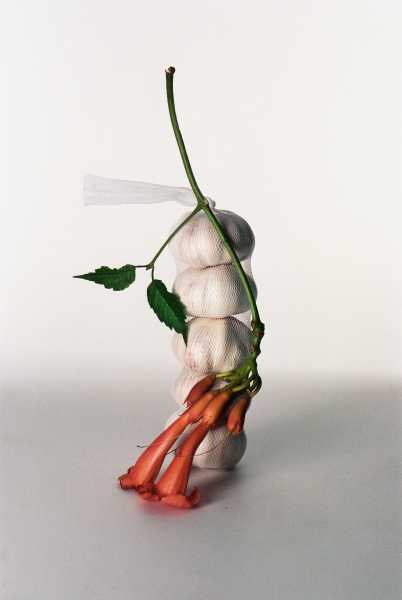

This is the case when Doherty photographs stylized arrangements in the studio, but also when he takes unposed images outside it, and “Dream About Nothing” includes examples of both. In one image, five garlic bulbs packed in a snood of grocery-store netting are positioned vertically against a stark white background, with a stubby vine of wilted red trumpet flowers propped against it, facing downward. The assemblage is so humble as to amount, at first glance, to nearly nothing, and yet it is also a poignant vignette, the garlic stack’s upward sweep barely resisting the dying bloom’s drag. In another image, Doherty captures, in extreme closeup, the hard, yellowish crust of a scab marring a patch of light freckled skin. The image is gross, but there is also something alluring and even sensual about it—the red puckered edges around the scab proffering it like a shiny gem, set in a prong. This jewel-like iridescence is repeated across many of the pictures in the book: in an image of a white cat with one blue and one hazel eye; in that of a dewdrop-laden bud, nearly touching the tip of a finger; or in one of a bunch of silvery fish heads, their dead eyes gleaming. There is also a fuzzy outline of a thatched-roof shack in a greenish mist; a trio of obscenely pink dumplings, snug in a bamboo steamer; and a well-fed toddler’s face, crumpled as if on the verge of emitting a cry.

In his commercial work, Doherty works digitally, but all the images in the book were shot in 35-mm. film, a technical choice that the photographer appreciates, partly, for its unexpectedness. “You never know what you’re going to get,” he told me. “It’s a crapshoot.” This embracing of chance pushes against the sense of control the photos convey. “I want someone to look at my pictures and have questions—what’s posed and what’s real, what’s sincere and what’s not,” Doherty said. His images can be seen as an “index of nonsense,” he went on. But that, too, is part of his credo. “I like to show people a card and then throw it away, pretending it doesn’t mean that much to me,” he said. “But it always does.”

Sourse: newyorker.com