Medicaid expansion doesn’t just provide more people health insurance — it appears to cut medical debt enormously, a new study has found.

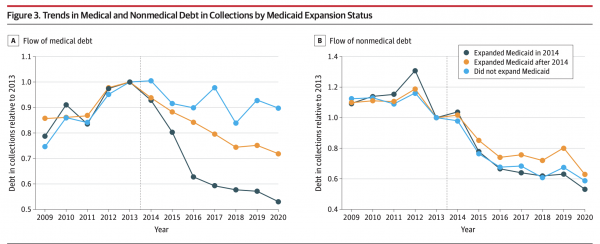

The Affordable Care Act offered states a huge infusion of federal money to expand Medicaid eligibility to low-income adults, and about 30 states took that deal right away in 2014. Since then, new medical debt in those states has fallen 44 percent, a dramatically bigger drop than was seen in the states that refused to expand the program over the same period. Those states showed only a 10 percent decline.

The study was published in JAMA by scholars from Harvard, Stanford, UCLA, and the National Bureau of Economic Research. The researchers noted that nonmedical debt had fallen by similar amounts in expansion and non-expansion states over the time period they studied, 2009 to 2020, strengthening the case that Medicaid expansion was the difference with medical debt.

Medical debt isn’t just bad for people’s finances or their credit rating. It’s bad for their health. The researchers noted high medical debt is associated with reduced health care use and, in general, people with more debt report worse mental health.

“This is a genuinely large effect,” Raymond Kluender, one of the authors and assistant professor at Harvard Business School, said in an email. “The Medicaid expansion was well targeted at a population that was extremely vulnerable to medical bills and who did not (and do not in states that have not expanded) have access to affordable health insurance.”

The states that expanded Medicaid in the years following 2014 experienced a meaningful but smaller reduction in medical debt than states that expanded that first year.

In states that expanded Medicaid, both the lowest- and highest-income groups saw their medical debt drop after expansion, but the amount of medical debt added annually decreased much more for the former (by $180, from $458 to $278) than the latter (by $35, from $95 to $60).

In non-expansion states, on the other hand, the lowest-income group averaged a $206 average increase in new medical debt, from $630 to $836. But the highest-income bracket still saw a small decline in new debt for medical care.

“Many of the states with the highest pre-ACA levels of medical debt did not expand Medicaid and subsequently did not experience substantial reductions in medical debt,” the researchers wrote when summarizing their findings.

Those states are concentrated in the South. Eight of the 12 non-expansion states are in the region. Nearly one in four Southerners have some medical debt in collections listed on their credit report, compared to 10.8 percent of people in the Northeast and 12.7 percent in the West.

This dramatic drop in medical debt after Medicaid expansion can be added to the large body of evidence documenting the benefits of the program. Research shows that people have more access to care and better self-reported health after Medicaid expansion. Cancer diagnoses come earlier, and patients are given the prescriptions for medications they need more often. A National Bureau of Economic Research working paper from 2019 concluded that states’ refusal to expand Medicaid had led to more than 15,000 deaths in one year that otherwise would not have occurred.

And as health economists Jonathan Gruber and Benjamin Sommers wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, states were able to implement expansion without a negative impact on their finances. Expanding Medicaid enabled them to cut back on other spending — for uncompensated care, care for people who are in the judicial system, and so on — while expansion was fully subsidized by the feds.

Democrats in Congress are working on a proposal to cover the 4 million uninsured people in non-expansion states who would be insured through Medicaid expansion. They want to include such a provision in their budget reconciliation bill later this year. A new expansion incentive passed as part of the American Rescue Plan has so far not persuaded most of the non-expansion states to reconsider their position.

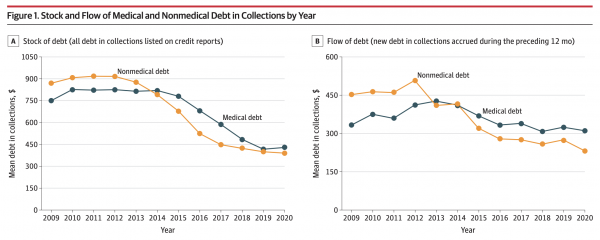

Overall, the improving economy from 2009 to 2020 led to a drop in all types of debt. But because medical debt declined less than nonmedical debt, there is now more of the former than the latter in the US, according to the new JAMA analysis of a nationally representative sample of depersonalized credit reports.

The total medical debt detected in the TransUnion credit reports reviewed by the researchers would translate to $140 billion in debt nationwide. An estimated 18 percent of Americans have some medical debt on their record. But there may also be additional debt not shown in the credit reports — for medical care paid for with a credit card, for example.

Still, the research is a good starting point for understanding the scope of the medical debt problem in the United States — and the difference Medicaid expansion can make.

Will you support Vox’s explanatory journalism?

Millions turn to Vox to understand what’s happening in the news. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower through understanding. Financial contributions from our readers are a critical part of supporting our resource-intensive work and help us keep our journalism free for all. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com