Democrats are trying to figure out how to pay for President Joe Biden’s infrastructure plan and raise hundreds of billions of dollars to put toward rebuilding American roads and bridges. And yet somehow one of the big internal battles happening on the left is not about putting in place a more progressive tax regime, but reinstating one that can look quite regressive.

In their 2017 tax bill, Republicans partially closed a tax loophole that mainly affected higher-income people in high-tax areas — i.e., relatively well-off people in blue states. They capped the state and local tax deduction (SALT) people can take when calculating their federal income tax at $10,000. People can still deduct state and local taxes from their federal tax bill, but only up to that point.

Many Democrats — namely, those from states such as New York, New Jersey, and California — want to repeal the SALT deduction cap and go back to the old regime, where people could deduct all (or at least more) of their state and local taxes. They argue the cap unfairly drives up their constituents’ tax bills, might keep their states from implementing more progressive tax regimes on high-income people, and was a vindictive move by the GOP in the first place.

“It was mean-spirited to begin with, politically targeted,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said at a press conference on April 1.

Sign up for The Weeds newsletter

Vox’s German Lopez is here to guide you through the Biden administration’s unprecedented burst of policymaking. Sign up to receive our newsletter each Friday.

But some Democrats, Republicans, and economists are saying hold the phone.

“The vast majority of the benefits of repealing the SALT cap would go to the people at the very top. It would also be costly — and for that amount, we could finance much more worthy efforts to support American families and workers. We can say we are for a progressive tax code and for fighting inequality, or we can support the SALT deduction, but it is really hard to do both,” said Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) in a statement to Vox. When the Senate took up a vote on whether to repeal the SALT cap in December 2019, he was the only Democrat to vote against it.

It’s an issue where, ideologically, the stars don’t entirely align: Rep. Katie Porter wants to scrap the SALT cap; JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon doesn’t.

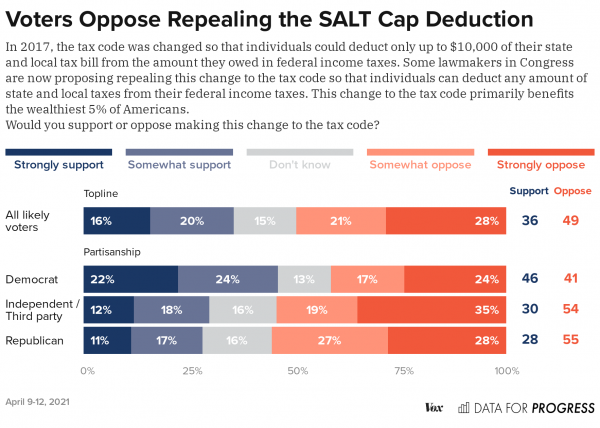

A poll conducted by Vox and Data for Progress found that repealing the SALT cap isn’t popular among the broader electorate. Independents and Republicans generally oppose axing it, though a plurality of Democrats support repeal. According to the survey, which was conducted from April 9 to 12 of 1,217 likely voters, urban voters were likelier to support repealing the cap than rural and suburban voters. The poll noted that restoring the full state and local tax deduction would primarily benefit well-off Americans.

Many moderate Democrats are arguing for the SALT deduction cap to be lifted, but so are some progressives. Take a look at New York Rep. Tom Suozzi, a moderate who represents parts of Long Island and Queens in New York, and has adopted “No SALT, no deal” as a sort of tagline on infrastructure as of late. “The first thing is just basic fairness, it’s not fair that you pay taxes on taxes you’ve already paid,” he said in an interview with Vox. Suozzi is joined by Reps. Jamaal Bowman and Mondaire Jones on the issue. They’re both Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez-aligned progressives and newly minted members of “the Squad.”

The debate over Democrats’ next move on infrastructure, which Biden has put forth as part of his American Jobs Plan, and whether and how to pay for it through taxes, is just getting started. Plenty of proposals are going to be on the table, including SALT. The White House has signaled some openness to it, but the matter is far from settled.

“If Democrats want to propose a way to eliminate SALT — which is not a revenue raiser, as you know; it would cost more money — and they want to propose a way to pay for it, and they want to put that forward, we’re happy to hear their ideas,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said at a press briefing on April 1.

SALT, explained

When people file their taxes, they can deduct certain expenses to make their taxable incomes lower. A lot of people just take the “standard deduction” and lop off a flat amount. Others, however, choose to itemize their deductions, so they can subtract things like charitable deductions and medical expenses. Generally, taxpayers choose whichever avenue will be more beneficial for them — as in, whichever will leave them with less income to be taxed.

For decades, taxpayers who itemized their federal income taxes could deduct what they paid in state and local property taxes and either income or sales taxes (whichever was higher). It was one of the biggest federal tax expenditures, according to the Tax Policy Center. “One way to view the deduction was as an indirect subsidy for states, and basically, the federal government was saying to taxpayers, ‘We’ll take up 37 percent of the cost of your state and local taxes,’” said Frank Sammartino, a senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

But with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 under then-President Donald Trump, that changed: The law capped the state and local deduction at $10,000. Sammartino explained who was hit: “If you’re high-income and in a state with high state and local taxes, this is going to bite you.”

The legislation also basically doubled the standard deduction from $6,500 to $12,000 for individuals and from $13,000 to $24,000 for couples, which softened the blow a bit. But for many taxpayers, it still stung.

Prior to the 2017 tax bill, about 30 percent of taxpayers itemized deductions on their federal returns, including claiming the SALT deduction. The higher-income the household, the likelier the deduction: In 2017, 16 percent of taxpayers with incomes between $20,000 and $50,000 claimed the deduction, compared to two-thirds of taxpayers in the $100,000 to $200,000 threshold and 9 in 10 taxpayers with incomes above $200,000. After the 2017 law, the proportion of people who itemize deductions on their taxes fell to about 10 percent, and an estimated two-thirds of them have an income of over $100,000. “Those that continue to itemize are generally high-income taxpayers,” Sammartino said.

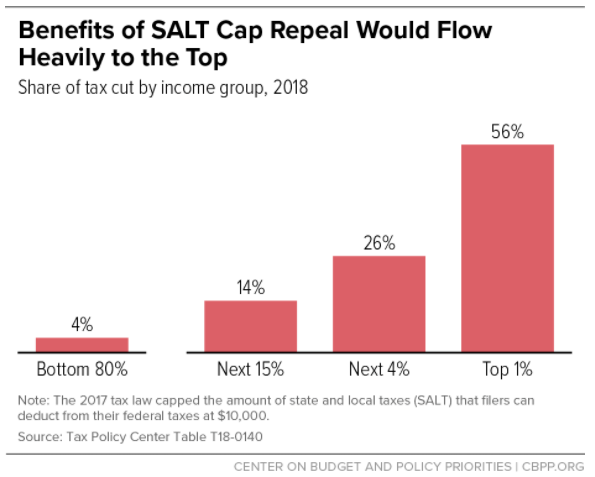

According to estimates from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, if the SALT cap — which is set to expire in 2025 — were to be repealed earlier, it would overwhelmingly benefit those at the higher end of the income scale — the ones who were hurt by the bill back in 2017. The CBPP estimates that more than half of the benefit would go to the top 1 percent, and over 80 percent would go to the top 5 percent, of earners.

The deduction is geographically concentrated as well. Prior to the TCJA, the 10 counties benefiting the most from the deduction were in four states: California, Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. And six states claimed over half of the deduction: California, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas. It’s popular in other states, too, including Utah, Minnesota, Virginia, Maryland, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, as well as in Washington, DC.

While the burden of the SALT cap falls disproportionately on high-income taxpayers in those states, it can affect other people, too. In a state like New Jersey, property taxes can be high even for people who aren’t superrich. And in New York City, $150,000 in annual income isn’t landing you in a Fifth Avenue penthouse. Still, given the data, it’s hard to argue that scrapping the cap on SALT deductions is squarely aimed at helping the middle class.

Some economists have even changed their minds on it. Jason Furman, President Barack Obama’s chief economist, did a tweet thread in 2017 that my colleague Dylan Matthews documented at the time, arguing lawmakers should keep the SALT deduction in place, making the case that Republicans were doing away with it to pay for tax cuts for even richer people (which, to a certain extent, they were). Furman has since described restoring the deduction as a “waste of money” and the “Democratic version of trickle-down economics.”

Jared Bernstein, one of Biden’s top economic advisers, isn’t a fan of putting the full SALT deduction back in place, either.

Why SALT isn’t settled: There are internal Democratic divisions over what to do

Many lawmakers — Democrats and Republicans alike — have been mad about the SALT cap since before the ink on the 2017 law was even dry. Since-retired Republican Rep. Rodney Frelinghuysen of New Jersey voted against the legislation in 2017, when he was chair of the House Appropriations Committee. He specifically cited the SALT limit in his reasoning, warning that it would “hurt New Jersey families who already pay some of the highest income and property taxes in the nation.” The SALT cap may have hurt Republicans in the 2018 midterms, as they wound up losing in some key impacted districts.

In 2019, the House of Representatives voted to roll back the SALT cap, with many Democrats and some Republicans going along. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) voted against the bill at the time, but she left the door open to doing something to “restructure” SALT. The bill failed in the Senate, which was then controlled by Republicans, but all Democratic senators voted for it except for one — Bennet from Colorado.

Now, SALT is back up for discussion as part of the broader conversation around Biden’s plan for spending on infrastructure and jobs, which includes talk of potential changes to the tax code. Some Democrats are pushing for the restoration of the full deduction or, at the very least, some changes to the current cap, to be included as part of a broader upcoming package, even though those changes would mean a decrease in revenue at a moment when the White House is looking to raise it. How on board Biden is with that is unclear: Axios reports the president isn’t planning to rejuvenate the SALT deduction, but there are some big names encouraging him to go along.

Pelosi has described the limit as “devastating” to California voters and said she shares the “exuberance” of lawmakers who are looking to do something about it. “Hopefully we can get it into the bill,” she said in April. “I never give up hope for something like that.”

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, who is up for reelection in New York in 2022, has also urged Biden to bring back the SALT deduction in full and has tried to further his argument by noting how hard-hit his home state has been by the Covid-19 pandemic. “Double taxing hardworking homeowners is plainly unfair; we need to bring our federal dollars back home to … cushion the blow this virus — and this harmful SALT cap — has dealt so many homeowners and families locally,” he said in a statement in January.

Some Democratic members of the House have gone as far as to declare, “No SALT, no deal,” in an effort to force the president’s hand on the issue.

“I’m going to talk to my colleagues on the Ways and Means staff and I’m going to talk to the White House and I am going to talk to my other colleagues that are in a similar predicament as my state is in,” Suozzi told Vox. “Right now, no SALT, no deal.”

Proponents of restoring the SALT deduction make multiple arguments. One is that capping it will cause wealthy people to flee high-tax states. There’s not really a lot of evidence for millionaire mass migration when their taxes go up. The SALT deduction is a relatively bigger hit, but there’s not clear proof that rich people are fleeing high-tax states en masse because of it — plus, people move for plenty of reasons. (See: the pandemic.) They also say that the SALT deduction lets state and local governments tax high-income people to pay for public services for low- and middle-income people. The reasoning goes that letting rich people deduct their state and local taxes means states can tax them more to pay for health care, education, public transit, etc., and that it stops states from engaging in a race to the bottom to cut taxes.

“For my progressive friends, I want to say very clearly, don’t be bamboozled by the conservative movement. They’ve been planning this for 40 years to figure out how to undo the progressive policies in progressive states by getting rid of the state and local tax deduction,” Suozzi said.

Richard Reeves, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution and co-author of A New Contract with the Middle Class, said that to the extent the SALT deduction is an attempt to accomplish those goals, it’s doing so in a very roundabout way. “The idea that the best way to get states to spend more money, particularly on services that are actually progressive, is to give a massive tax break to the people who live there in the hopes that it will allow the states and cities to therefore tax them a bit more because they know they’ve got a break, and that that extra revenue will be used in a progressive way — that might be happening, but wow, that’s a pretty long way around,” he said.

Democrats also make the point that the deduction limit wound up in the 2017 tax bill as a way for Trump to exact revenge on blue states that didn’t support him. “The notion that if Democrats had enacted a policy specifically targeted at Texas and Florida, the members from Texas and Florida wouldn’t try to reverse it … obviously [they would] if the shoe were on the other foot,” one Democratic aide said. “Republicans were so clear about what they were doing in 2017, they wanted to shift money from wealthier people in New Jersey and New York to wealthier people in Texas and Florida and other red states.”

Reeves sees it a different way: “Good policy gets made for bad reasons.”

This is really an issue of politics meets policy

The fault lines around the SALT deduction aren’t really so ideological as they are geographic, which makes sense, given whose constituents are impacted by this and whose aren’t. It’s a non-issue for voters in many parts of the country, but in places where it matters, it really matters: Rep. Mikie Sherrill, the Democrat now representing the district Frelinghuysen retired from, ran ads during the 2018 about the SALT deduction.

The Congressional Progressive Caucus, which represents the left-leaning faction of the House, has declined to take a position on the matter — its membership is split. “There are some members that feel very strongly about it because they’re in a state where that’s a very big issue for their revenue,” Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), the CPC’s chair, told the Hill.

The politics of the SALT deduction are a bit messy, but the bigger issue is really the policy angle, said Celinda Lake, a Democratic pollster who advised Biden’s 2020 presidential campaign. The Biden team wants to raise revenue to pay for infrastructure and other priorities, and lifting the SALT cap will do the opposite. It would cost an estimated $600 billion through 2025.

“I don’t think it has much downside politically; it’s more of a dilemma for the economic team and the budget team,” Lake said. “Democrats right now are concentrating on who’s not paying their fair share as opposed to who’s paying their fair share.”

The debate over what to do about the SALT deduction doesn’t have to be a binary one. There are other alternatives, like reducing all itemized deductions or limiting the tax rate applying to itemized deductions. Or the federal government could raise the SALT cap to $20,000 for couples to at least get rid of the marriage penalty currently in place, or raise the top individual income rate back to 39.6 percent, where it was pre-TJCA.

“If you wanted to raise revenue from higher-income people, you could just raise the top rates. It’s pretty straightforward, and it doesn’t distinguish between different regions of the country,” Sammartino said.

Reeves chafed at the idea of raising the top rate to counterbalance lifting the deduction cap. “Why would you take with one hand and give back with the other? Why not just take with one hand and make the tax code a bit simpler?” he said. He instead pointed to a proposal from the Tax Policy Center for the federal government to help create a kind of “rainy day fund” to help states.

Lake said she believes it would be “fairly easy to obtain some kind of compromise.”

Biden ran on his ability to bring Democrats and Republicans together. It’s become increasingly obvious Republicans aren’t coming along for the ride with him on much of anything, and even though some of them might want to restore the SALT deduction, it’s likely to be tucked into a broader package that the GOP isn’t going to go for. And so the challenge on state and local taxes, as with so many other issues, is for the White House and congressional leadership to keep Democrats together. The debate on this, and myriad other tax proposals, is just beginning.

Vox turns 7 this month. Although the world has changed a lot since our founding, we’ve held tight to our mission: to make the most important issues clear and comprehensible, and empower you to shape the world in which you live. We’re committed to keeping our unique journalism free for all who need it. Help us celebrate Vox’s 7th birthday and support our unique mission by making a $7 financial contribution today.

Sourse: vox.com