During the summer of 2016, while the contentious presidential race between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump was in full swing, Facebook and Twitter found themselves transformed into uneasy partisan battlegrounds. And strange events were happening there, set into motion by Russian propagandists.

They purchased Facebook ads to promote real-life pro-Trump rallies, according to special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation and his subsequent indictments. Russians also bought ads spreading voter fraud conspiracies and touted an event to “support Hillary” and “save American Muslims.”

On Twitter, a Russian-created account that falsely claimed to be controlled by Tennessee’s Republican Party attracted more than 100,000 followers during the election season. Another Russia-created Twitter account recruited and paid a real person to dress up as Clinton in a prison uniform at a rally in West Palm Beach, Florida. No one at either tech company seems to have batted an eye — at least not until the election was over, and Trump was voted president.

Financial institutions in the United States are subject to extensive regulatory standards that require them to know their customers and understand the source and destination of client financial transactions. They are generally barred from doing business with individuals, businesses, and governments subject to sanctions, or even touching money that might be connected to sanctioned entities.

Because of legislation such as the Bank Secrecy Act, signed into law in 1970, and the Patriot Act, which was made law in 2001, those institutions must maintain strict compliance programs to monitor for signs of money laundering, terrorist financing, and other criminal acts, and they are obligated to report suspicious activities to authorities.

As the evidence continues to mount that Russia used social media and tech platforms to interfere in the 2016 election, it might be time to think about what responsibilities companies have regarding knowing their customers and what they’re doing. Citibank and JPMorgan have to know whose money they’re dealing with — but should Facebook and Twitter, too?

Banks have a lot of regulatory oversight. The tech industry doesn’t.

Experts say there’s no one-to-one translation between the laws that govern banking and the laws that might govern tech. “It’s kind of apples and oranges,” Peter Hardy, a partner at law firm Ballard Spahr LLP, said. But making an attempt to do something is necessary, as there is every indication that Russia will continue to try to meddle in US elections moving forward — and it will use the internet to do it.

Renee DiResta, the head of policy for the nonprofit Data for Democracy, agrees. “The financial industry has been subject to regulation for a century, and the tech industry has largely skated by without being subject to any similar regulatory framework because it’s still relatively new,” she said. “We haven’t been particularly worried about ensuring integrity in social networks until very recently.”

“They should know who’s paying them,” said Vasant Dhar, a professor of information systems at New York University, “because the consequences are very serious.” In December, Dhar wrote an op-ed calling for social media regulation — specifically, something similar to the Know Your Customer laws that apply to banks. “The US government and our regulators need to understand how digital platforms can be weaponized and misused against its citizens, and equally importantly, against democracy itself,” he wrote at the time.

Antonio García-Martinez, Facebook’s first targeted ads manager, thinks so too. “For certain classes of advertising, like politics, a random schmo with a credit card shouldn’t just be able to randomly run ads over the entire Facebook system,” he told me.

There are no simple solutions — the internet was created as a free, open space, and the idea of regulation is almost contrary to its reason for being. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit focused on digital liberties, has warned policymakers of the dangers of going too far in their efforts to counter foreign influence in US elections. It filed comments with the Federal Election Commission in November advocating a solution that “balances the need for transparency with the critical role that anonymous political speech plays in our democracy.”

But even Tim Berners-Lee, widely considered the inventor of the World Wide Web, has said some oversight is necessary. In a recent blog post marking the internet’s 29th birthday, Berners-Lee warned that the concentration of power in companies such as Facebook and Twitter has made it possible to weaponize the web at scale.

“The responsibility — and sometimes burden — of making these decisions falls on companies that have been built to maximize profit more than to maximize social good,” he said. “A legal or regulatory framework that accounts for social objectives may help ease those tensions.”

Paid advertisements are probably the best way to start

Political contributions and spending by foreigners has been outlawed for decades. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, a campaign finance law sponsored by Sens. John McCain (R-AZ) and Russ Feingold (D-WI), required the open

Under current law, foreigners can’t pay for Facebook for ads that explicitly say to vote for or against a candidate, but they can pay for ads that only mention a candidate, and ads that promote specific issues instead of individuals, Paul S. Ryan, vice president at watchdog group Common Cause, told me. And they don’t have to say where that money is coming from.

In October, McCain joined Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Mark Warner (D-VA) to introduce the Honest Ads Act, which seeks to regulate online political advertising in the same way the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act does television, radio, and print.

“The Honest Ads Act would extend the McCain-Feingold law ‘electioneering communication’ provisions — i.e., TV/radio ads that name a candidate within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election but do not expressly advocate the candidate’s election or defeat — to certain online ads,” Ryan said. “I call these ‘candidate-specific issue ads’ or ‘sham issue ads’ to distinguish them from legitimate issue ads that don’t attack or praise candidates right before an election.”

The Honest Ads Act would require social media companies to disclose what groups are running political advertisements and make “reasonable efforts” to ensure foreign governments and agents aren’t purchasing ads on their platforms.

That said, not everyone thinks the proposed law could be the whole solution. Sandy Parakilas, a former operations manager at Facebook who has advocated for stricter regulations on the company, told me the Honest Ads Act might be a good start, but that it’s no panacea. “It doesn’t solve the problem with issue-based ads,” he said. “It’s one thing if it’s, ‘Vote for Donald Trump,’ but if you’re saying, ‘Join the Heart of Texas group,’ which was a fake Russian propaganda page, that’s not electioneering.”

A lot of the Facebook ads and sponsored content Russians have pushed have been issue ads on LGBTQ rights, guns, and Islam, which would not be regulated under the Honest Ads Act. Some of their ads just mention candidates but don’t expressly advocate for them, and those would be regulated.

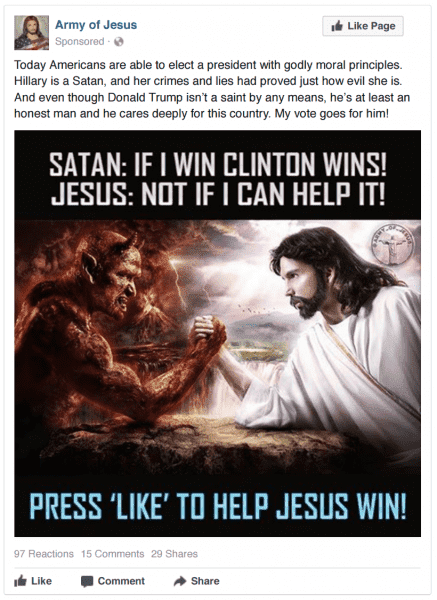

The House Intelligence Committee released multiple samples of Kremlin-linked ads last fall as part of its Democratic members’ efforts to demonstrate the scope of Russian activity during the 2016 election.

One California state legislator has also put forth a proposal to his state’s legislature that might address those issues. In January, Assemblymember Marc Levine, a Democrat, proposed legislation that would require a disclaimer be displayed on automated accounts — essentially, a sort of sticker that says “I’m a bot.” It would also require that all bot accounts be connected to a verified human and that advertisements be purchased by real people. While his bill has been referred to two committees, no hearing dates have been set.

“They built the car and they allowed the Russians to get in it, gave them the keys, and allowed them to go speeding on the highway. And then they wrecked that car into our democracy,” Levine told me. “So big tech needs to take responsibility for the software that they are creating.”

It’s really hard to stop the bots, and regulation probably can’t do it

Special counsel Robert Mueller’s indictment outlined the efforts of the Kremlin-linked Russian troll farm known as the Internet Research Agency, which spread false stories and propaganda using thousands of accounts. Twitter found more than 3,800 accounts linked to the group and alerted 1.4 million US users that they may have interacted with their propaganda in January. Facebook testified that about 126 million Facebook users had seen Russian-linked content and rolled out a tool for users to find out if they had.

It’s important to note that the bot problem isn’t just Russian. In January the New York Times published a lengthy report on the business of buying and selling fake followers on social media, which focused on a single obscure American company named Devumi. Devumi essentially buys fake accounts from a variety of “bot makers” and then sells them to customers looking to increase their social media reach for as little as a penny per account. The business model isn’t necessarily malicious, but it is manipulative and dishonest.

Twitter recently purged a number of bot accounts from its platform. But stopping them entirely on Twitter or Facebook is next to impossible. The scale of policing everyday accounts compared to advertisements is fundamentally different; there may be a few million advertisers on Facebook and Twitter, which is much easier than trying to comb through billions of users.

“It’s arduous, and it’s really not necessary, because as long as the platforms are okay with anonymity, and we assume that most people are operating in good faith, their basic checks are catching a fair amount of accounts,” DiResta, from the Data for Democracy nonprofit, told me. “I personally do not think the platforms are going to be implementing Know Your Customer for everybody who opens an account. But when they’re spending money to influence people, it absolutely makes sense.”

Sen. Klobuchar said in a February interview on NBC’s Meet the Press that fining companies such as Facebook and Twitter for failing to purge bot accounts would be a “great idea,” but acknowledged the limitations. “Then you need a Congress to act, and there are too many people that are afraid of doing something about this. Because we know these sites are popular,” she said, adding that ad spending is “much simpler to regulate.”

There’s also a First Amendment question. Should Facebook and Twitter users, even the bots, be able to say what they want on the internet?

“There are a number of reasons that people don’t want their identities known on the internet,” former Facebook operations manager Parakilas said. “But if you’re talking about truly automated accounts that are operated in huge numbers, that is a huge problem, and reducing that doesn’t limit anyone’s freedom of speech.”

A lot of it depends on Facebook and Twitter, too

Bureaucracy is notoriously slow to adapt to new technologies, which means a lot of the effort to stymie Russian political malfeasance will need to come from the platforms themselves. Facebook, Twitter, Google, and other companies already collect plenty of data on their advertisers — and spend a lot of time policing them, too.

García-Martinez, who worked on Facebook’s targeted ads from 2011 to 2013, told me the company could probably use a strategy similar to the ones it uses in other advertising arenas. Alcohol ads, for example, are only shown to users of a certain age in the United States, another age in Spain, and not at all in Saudi Arabia, where alcohol is illegal.

“Facebook actually goes in and programmatically figures out what’s an alcohol ad and then applies business logic to it saying what’s allowable,” García-Martinez told me. “And if you break the rules enough, the account gets frozen.” That system isn’t perfect, but it would be a start.

There are signs Facebook and Twitter are making an effort to police their platforms. Ahead of their congressional testimony last fall, both Twitter and Facebook announced new transparency and authentication efforts for advertising. Twitter announced an “advertising transparency center” to disclose information about its ads, and Facebook said it would require political advertisers to verify their identities and would include

Beyond that, Twitter is purging obvious bots and has informed users who engaged with Russian propaganda. Facebook has adjusted its news feed to emphasize more posts from friends and family, disclosed many of its findings about the 2016 election, and will mail postcards via US mail to advertisers when people create certain political ads.

In January, the company bought Confirm, a Boston-based software company that specializes in making sure government-issued IDs, like drivers licenses, are authentic, which is a sign it’s thinking about customer verification. “They’re trying to get ahead of regulation because they can smell it in the air because the tide has turned in terms of public sentiment,” García-Martinez said.

Of course, it’s not clear how strong the impetus is for Facebook, Twitter, or others to get serious about self-policing. They are publicly traded companies that ultimately respond to their shareholders. Money is money. Ahead of stories from the New York Times and the Guardian on how Cambridge Analytica, an American Trump-linked data firm, and SCL Group, its British parent company, harvested data to get information from some 50 million Facebook users, Facebook refused to acknowledge it. Only the day before the stories published did the company post a statement expressing concern.

“Facebook clearly has a regime where they’re tracking who’s buying ads, how much they’re buying, etc.,” said Greg Xethalis, a lawyer at Chapman and Cutler who specializes in financial services and emerging technologies. “I would suspect the Know Your Customer they’re doing on their ad purchasers is probably driven more by what information they need for internal business purposes and to best sell ads rather than to satisfy information requests from any third parties, such as the Federal Election Commission, the Department of Justice, etc.”

Facebook’s issues with knowing their customers goes beyond political advertising as well. The company also owns WhatsApp, an encrypted messaging app that entities such as the FBI and CIA can’t crack. There is major concern globally that WhatsApp can help hide financial and other crimes — but, of course, encryption is part of the product’s appeal. In the case of political ads on Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Instagram, which Facebook owns, it’s similar: low-cost political speech is a benefit the internet offers that companies and users enjoy.

“I have yet to see that steps that I think they really need to take, which is to allow third parties to come in and audit their platforms in the same way they allow third parties to audit their financial information, and just to be more open to regulation and to accept liability for when truly terrible things happen,” Parakilas, the former Facebook operations manager, said.

There is little doubt that Russia is going to continue its interference operations in United States politics in 2018 and beyond, or that others are going to try to leverage the enormous amounts of data users have voluntarily given to social platforms over the years for their benefit. It’s going to take a multi-dimensional effort to tackle it. That includes making sure social media companies know who they’re dealing with, especially when money is changing hands.

“These are the very early days of rethinking the regulatory framework,” DiResta said. “What we’re seeing now is going to be the tip of the iceberg.”

Sourse: vox.com