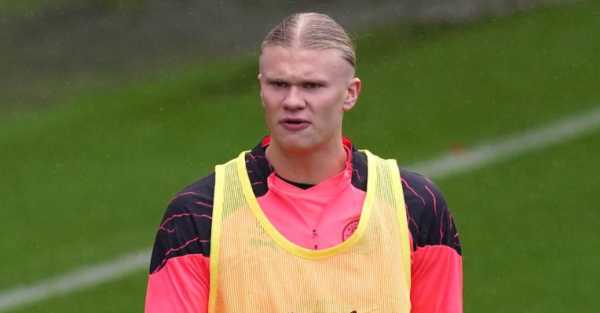

Erling Haaland has eased fears over his fitness by training ahead of Manchester City’s Champions League clash with Young Boys.

The prolific Norway striker has been a doubt for the Group G clash at the Etihad Stadium on Tuesday after twisting his ankle against Bournemouth at the weekend.

Haaland, who has scored 13 goals this season, showed no obvious sign of discomfort as he participated in a training session open to media on Monday afternoon.

Earlier in the day manager Pep Guardiola had said the 23-year-old would be given every opportunity to prove his fitness and that Sunday’s trip to Chelsea would not influence his thinking.

“Yesterday he told me he felt much better than the day of the game but I don’t know,” said Guardiola at a press conference.

“I will listen to the doctors and himself. If he says he is ready and does not have pain I will consider to let him to play because from Tuesday to Sunday there’s a lot of days to recover.”

After winning their opening three games in the competition, Champions League holders City can secure their place in the last-16 with a second victory over the Swiss champions following their 3-1 success in Bern last month.

“Tomorrow we have to try to do it, to finish it,” Guardiola said. “There will be more opportunities, but we have the chance to finish and qualify for February, for the next stage, and it means a lot for the club.

“Being there is a success and every time we qualify is really good.”

Reaching the next stage at the earliest opportunity would potentially allow Guardiola to rotate his squad and prioritise the Premier League fixtures against Liverpool and Tottenham that sandwich their next European outing against RB Leipzig on November 28.

Guardiola, however, maintains there will be no easing up before top spot in the group has been finalised.

He said: “We are not (definitely) first. To try to be first, to have the chance to play the second game (of the last-16 tie) at home, that definitely is better.”

Guardiola, who was speaking to media to preview the Young Boys game, was also quizzed on the Premier League’s latest VAR controversy.

Arsenal branded the standard of officiating in the competition as “unacceptable” over the weekend after they lost to a contentious goal at Newcastle.

Gunners manager Mikel Arteta had said the decision to allow Newcastle’s winner, after a triple VAR check, was an “absolute disgrace”.

Guardiola said: “The emotion after the game, it is difficult for the managers right after we finish, being here and talking about the feelings. It’s difficult to handle it.

“But I’m talking for myself. I’m not talking for Mikel or for any other manager.

“It’s so sensitive an issue right now. It’s difficult for the referees too, for everyone. Honestly I don’t have a clear opinion.”

Guardiola was joined for pre-match media duties by Rico Lewis.

The 18-year-old defender or midfielder was recently described by Guardiola as “one of the best” young players he has trained.

Lewis said: “It’s quite difficult to comprehend that someone like that would say something like that about myself. Obviously it’s an amazing comment, but I’ve got to carry on doing what I can do.”

Sourse: breakingnews.ie