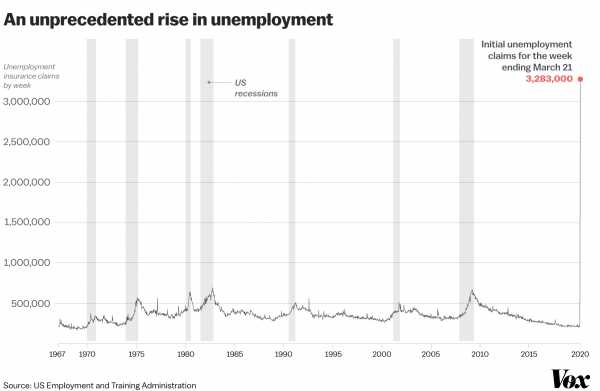

This raises an obvious question: Are enough of these people going to get unemployment insurance? And if they do, will they get enough money?

On March 18, Congress passed a bill offering $1 billion to states to help them sort through the historic surge in unemployment. But they realized this was nowhere near enough. Now, Trump has signed into law the third legislative package responding to the coronavirus crisis, authorizing a big boost to unemployment insurance benefits.

The centerpiece of the new plan is a $600-per-week across-the-board increase in unemployment benefits for all workers claiming them. Given that as of January the average UI check was $385 per week, this is a massive increase.

The package promises these higher benefits for UI recipients for up to four months (Democrats successfully pressured Republicans to increase the number from three). The bill creates a new program, Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, for self-employed and contract workers who are typically ineligible for UI. It provides some incentives for work-sharing, a program whereby the government covers a portion of lost wages for workers whose hours have been reduced. The intention here is to incentivize companies to retain workers by just employing them for less time.

Related

How the Covid-19 recession could become a depression

For all the increase in assistance, UI experts agree that the package could be improved. “It does some things well,” Arindrajit Dube, a professor of economics at UMass Amherst, who released an influential plan for boosting UI benefits during the recession, says, but “some/many workers seeing hours cuts will fall through the cracks.”

Chad Stone, chief economist at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and an expert on UI policy, told me, “In the grand scheme of things it’s pretty good, albeit temporary.” The biggest problem is that its most important provision, the $600-a-week bump in benefits, expires at the end of June. And it doesn’t include some modernization measures that policymakers have wanted for years. But it does represent a big temporary investment in helping people put out of work.

How unemployment insurance works normally

Unemployment insurance has existed in its modern form since it was created in 1935 as part of the same legislation that created Social Security. It’s funded by state employment taxes and by the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA), which is 6 percent of the first $7,000 in each employee’s wages. States can levy their own taxes that can replace up to 5.4 percent of the 6 percent tax.

Because it’s administered by the states, the generosity of UI varies widely. Most states offer up to 26 weeks of UI, but some offer far less: Florida and North Carolina offer only 12 weeks currently, though their generosity increases with the state unemployment rate. Missouri offers only 13 weeks per statute, a number that doesn’t increase with the unemployment rate.

There’s similarly large variance in the recipiency rate — the share of unemployed people getting UI — and benefit size as a share of the average weekly wage. The highest recipiency rate is in Massachusetts, where 57 percent of unemployed people get benefits. In North Carolina, only 10 percent do. In Hawaii, the top state for generosity, the average benefit is 55 percent of the average weekly wage; in the worst state, DC, it’s only 21 percent of wages (Arizona and Louisiana aren’t far off with 23 percent). There are many causes of this variance, but a lot of it boils down to state-level policy: Most of the low-receipt, low-benefit states are choosing to be stingy.

For years, experts at think tanks and elsewhere have been urging Congress to modernize the unemployment system, to bring more consistency to state systems, replace a higher share of pre-unemployment income so unemployed people can pay rent and afford groceries, and expand benefits to contractors and self-employed people. The most notable plan came out in 2016 from the Center for American Progress, the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, and the National Employment Law Project. The Obama administration proposed UI modernization in its final year, but the plan went nowhere.

In 2008, Congress initiated a program called the Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program, similar to a program that existed during the early 1990s recession. At its peak, it offered up to 53 additional weeks of benefits in addition to standard coverage in states with especially high unemployment, funded by the federal government, for a total of up to 79 weeks in states with 26 weeks of unemployment coverage.

There is also a permanent UI program called “Extended Benefits” that can kick in automatically, but it’s half-funded by states, which reduces its viability during downturns when states are cash-strapped, and its “triggers” for availability were less likely to kick in than EUC’s. Even at its peak, it only offered 20 extra weeks of benefits for certain states with especially high unemployment, pushing the total number of eligible weeks up to 99, on top of EUC and normal benefits.

What the stimulus law does for UI

The new stimulus law’s most notable provision adds $600 per week on top on every unemployment check for four months. That’s a massive expansion in the generosity of the program; Dube says it “would increase benefits for eligible workers more than raising the replacement rate from say 40 to 85 percent,” and would push the replacement rate beyond 100 percent for workers with weekly wages below $600.

But there are other important provisions as well. It expands unemployment insurance to contractors, the self-employed, and nonprofit/government employees who are not typically eligible. It revives the “Emergency Unemployment Compensation” program but only for 13 additional weeks on top of states’ standard; that limits the total benefit period for states with 26 week programs to 39 weeks, compared with 99 weeks maximum during the Great Recession.

Many states have a one-week “waiting period,” meaning that the first week a person is unemployed, they get no benefits. This bill pushes states to waive that period by paying the full cost of that week of benefits. States with work-sharing programs (also called “short-term compensation”) have their full work-sharing costs covered by the federal government; those interested in setting up such a program get assistance in paying startup costs, and a 50 percent match in expenses.

Dube is particularly nervous about these work-sharing and hours-reduction provisions. Suppose someone loses half their hours and applies for unemployment. “It’s not clear if someone loses half their hours and claims partial benefits, will they just get their inadequate 50 percent replacement rate for lost hours or also a pro-rated enhanced benefit?” he notes.

Beyond that, both Dube and Stone expressed concern about the short duration of the program. The $600 bump expires as the end of July, and it’s far from clear that the crisis will be over then. Dube additionally notes that beyond the $600, there’s little for people with too little earnings to normally qualify for unemployment insurance. He suggested that the program should lower the minimum earnings requirement to allow poorer workers, or workers without much earnings history like people graduating from high school or college in 2020, to benefit.

We could have had this automatically

In the future, we don’t need to scramble to pass emergency legislation like this.

Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO), who has also been helping lead the effort to make unrestricted cash part of the economic response to the coronavirus, has a new plan to boost unemployment insurance to make it more effectively cover workers both in emergencies like now and afterward, that he shared exclusively with Vox.

The plan was already in the works well before the coronavirus crisis, as part of a package of “automatic stabilizers” that Bennet was developing.

The plan would vastly ramp up “extended benefits,” the long-neglected part of the UI system mentioned above that is already part of the unemployment insurance law, and adds emergency money during large downturns. Bennet’s plan would fully federally fund the program, taking pressure off states, and trigger extended benefits automatically when the unemployment rate spikes, or if it ever exceeds 6.5 percent. It would set benefits to 100 percent replace wages, up to a maximum level (set at 80 percent of the median wage) during public health emergencies like the coronavirus.

It would also impose stricter rules on states to make them push minimum weeks of coverage up to 26 weeks, and minimum replacement rates up to 75 to 80 percent. That could increase generosity even in already generous states; recall that Hawaii, at the top of the list, only replaces 55 percent of the median wage. The bill, consistent with Bennet’s interest in a child allowance, would mandate at least $25 per week as a dependent’s allowance for children of unemployed workers.

The bill also includes sub-minimum wage workers like those with disabilities or tipped workers, by allowing people with lower incomes to qualify for UI. It also changes rules so that benefits are based on more recent wages, increasing the program’s generosity and making it more attractive. Finally, the bill would make leaving one’s job for compelling family reasons an eligible cause for unemployment insurance. Right now it can be difficult to get benefits if one hasn’t been explicitly fired.

There are a lot of details to the Bennet bill, and proposals for automatic benefits are likely to evolve considerably as this crisis continues. But it answers an important need: for legislation that expands UI even when Congress is too busy arguing to do so. If Bennet’s bill had been passed last year, say, we arguably wouldn’t have needed an emergency intervention by Congress in response to the coronavirus.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter and we’ll send you a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling the world’s biggest challenges — and how to get better at doing good.

vox-mark

Sign up for the

newsletter

Future Perfect

Email (required)

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice and European users agree to the data transfer policy.

For more newsletters, check out our newsletters page.

Subscribe

Future Perfect is funded in part by individual contributions, grants, and sponsorships. Learn more here.

Sourse: vox.com