“Madre mía,” said Luis Enrique, shaking his head and waving his hand from one side to the other for added effect. “Where did this kid come from?”

Achraf Hakimi, Hakim Ziyech, Youssef En-Nesyri, Sofyan Amrabat. Luis Enrique and his coaching staff were ready for them all. But not the skinny midfielder with the number eight on his back. “I’m sorry, I can’t remember his name,” added Luis Enrique.

He will remember it now and he is not the only one. Morocco’s Azzedine Ounahi has been a World Cup revelation.

“He can really play,” continued the now former Spain manager, putting the emphasis on really, his eyes widening as he spoke in his press conference, his final press conference, in the wake of Tuesday’s game at the Education City Stadium. “He surprised me.”

- Messi, Ronaldo, Neymar can still make this their World Cup

- Luis Enrique leaves role as Spain boss after Morocco loss

- Who plays who in the quarter-finals? | World Cup schedule

Moroccan fans celebrated their historic World Cup win against Spain in London, Doha and with the players when they returned to their team hotel

He surprised most people, in truth, the 22-year-old excelling as Morocco claimed a famous win over Spain to propel them into the quarter-finals of the World Cup for the first time, but not everyone.

Trending

- Transfer Centre LIVE! PSG chief: Impossible to have Neymar, Messi, Mbappe & Ronaldo

- World Cup LIVE! Phillips reveals Rice boost | Sterling returns to Qatar

- World Cup 2022 schedule: QF line-up confirmed

- PSG president: Messi happy in Paris | Rashford for free in the summer? Why not?

- Arteta unsure on Jesus return | ‘When we know timescale we’ll look at options’

- Portugal deny report Ronaldo threatened to quit World Cup

- England vs France: How tactics, styles and players compare ahead of showdown

- WNBA star Griner released by Russia in prisoner swap

- World Cup quarter-final predictions: Michael Oliver to deliver Croatia cards

- Brook ‘was going for’ fastest hundred | ‘Test cricket the pinnacle’

- Video

- Latest News

Not those at Morocco’s Mohammed VI academy in Salé, of which he is a graduate, like many in Walid Regragui’s team; or those at US Avranches, the tiny, third-tier club in northern France where his senior career really began, only two years ago, and where he is fondly remembered as their petit protégé.

“I wouldn’t say he was destined, with total certainty, to play at the highest level, because he needs an environment where he is trusted, with a coach who allows him to show his qualities,” Corentin Bouchard, former assistant coach at Avranches, tells Sky Sports.

Also See:

“But he was so talented, that was clear in every training session, and we always hoped he would get there. He had strong technical qualities, both to keep the ball and to unbalance a team by passing, dribbling or shooting. On top of that, he had very, very impressive stamina, which allowed him to repeat his efforts again and again.”

It was all there against Spain. When he wasn’t dancing away from opposition defenders, the ball seemingly glued to his feet, as he did so brilliantly to create a glorious chance for Walid Cheddira in the first half of extra-time, Ounahi was hustling, harrying, anticipating.

Image: Morocco’s Azzedine Ounahi challenges Spain’s Gavi in the last 16 tie

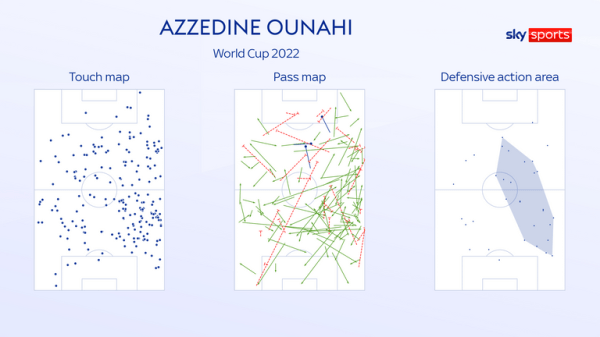

He was everywhere. The tracking data proved it. According to FIFA, Ounahi covered a remarkable total of 14.7km before his 119th-minute substitution – the most by any player on either side.

“He didn’t stop running,” added Luis Enrique.

“He must be exhausted.”

The game against Spain was Ounahi’s fourth consecutive start of the World Cup but only a year ago he was uncapped.

It has been some rise and it is all the more impressive considering how recently he was turning out in front of crowds of a few hundred in France’s Championnat National.

Ounahi arrived at Avranches having failed to earn a professional contract with Strasbourg, where his playing time had been limited to the club’s second team following his move from Morocco in 2018.

Image: Azzedine Ounahi has played on the right of Morocco’s midfield three

“The only thing he lacked at this level of competition was maybe in recovering the ball during duels,” adds Bouchard. Ounahi was slight in stature and still is. But playing regularly for Avranches helped build him up – mentally as well as physically.

“He developed a lot of confidence from that, but his technical qualities and his physical qualities, in terms of his stamina, were already there,” says Bouchard. “We just tried to develop his quality in the last meters, to be even more decisive.”

Ounahi is remembered as “quiet and reserved” in the dressing room – “he spoke more when were in smaller groups,” says Bouchard – but “approachable” too, and with an inner-belief in his own ability.

“He is someone who has ego and character, but who also listens to what is said to him and is very respectful and affectionate,” adds Bouchard. “That’s why he was like our little protégé.”

Still, though, his physical stature was off-putting to many suitors.

“He was followed, but most clubs weren’t willing to take a risk on him,” says Bouchard. “Scouts sometimes found him too fragile to imagine him playing in Ligue 1 or Ligue 2.”

Image: Azzedine Ounahi joined Angers from US Avranches in July 2021

That gave Angers, a top-tier outfit from the western edge of the Loire Valley, a relatively clear run at him when they made their move in the summer of last year.

“There were several clubs looking at him, but Angers was the only one from Ligue 1,” Gildas Crozon, a journalist who covers the club for the Courrier de l’Ouest newspaper, tells Sky Sports.

The step up to Ligue 1 certainly tested him physically.

“He had something different from the other players in midfield, he was very skilful, but he was skinny, and not very strong,” says Crozon. “When he played against very strong players who put a lot of pressure on him, it could be more difficult.”

But the self-belief previously noted by Bouchard at Aranches helped Ounahi through. “Azzedine is very confident in his skills,” adds Crozon. “He really knows that he can – and that he could at the time – be a regular player in Ligue 1. I don’t think he found it difficult to adapt to Ligue 1. I think he knew that he could do that.”

By the end of the season, he had made 32 appearances, 16 of them as starts, as Angers finished 14th, the youngster breaking into Morocco’s senior side for the first time in the process.

His impact at international level was profound.

In fact, on only his third start, in the second leg of Morocco’s World Cup qualifying play-off against DR Congo in Casablanca in March, he scored two goals – the first a superb, long-range effort – and set up another in an emphatic 4-1 win which clinched their place in Qatar.

Image: Azzedine Ounahi joins his Morocco team-mates in celebration during the group stage

Crozon describes it as a “moment that changed everything” for Ounahi in his homeland – “he was a young player who was not that well-known in Morocco, but suddenly he was iconic,” he says – and the summer brought speculation over his future.

Spanish clubs, including Sevilla, were said to be interested – “a fee of 12 million euros was mentioned,” says Crozon – but eventually he signed a new four-year contract with Angers.

“The coach, Gerald Baticle, told him he had to be more important for the team, a leader,” says Crozon. “He told him he was counting on him. In the first game of the season, he showed us he was ready.”

Crozon describes Ounahi’s performance in that game, a goalless draw with Nantes in which he was up against former Tottenham and Newcastle midfielder Moussa Sissoko, as “incredible”.

Sissoko agreed.

“Sissoko said afterwards that he didn’t know Azzedine,” says Crozon. “It was similar to what Luis Enrique said about him, a guy not known by anyone but the best player on the pitch.”

From there, though, the season quickly became difficult.

Ounahi has still shown his quality, with only a certain Lionel Messi completing more dribbles among all Ligue 1 players, but Angers sit bottom, five points adrift of safety with only two wins from 15 games. There has been tension with the club’s supporters too.

Image: Azzedine Ounahi ranks second in Ligue 1 behind Lionel Messi

“The level he has shown at this World Cup is not the level he has shown at Angers this year,” says Crozon. “Then, Azzedine and Sofiane Boufal, who also plays for Morocco, didn’t play in the last game before the World Cup against Lille.”

It was deemed controversial. Even more so when Angers lost 1-0, and still more when Baticle paid for it with his job. Ounahi had broken his nose earlier in November but, according to Crozon, some fans have doubts. “They feel that maybe Azzedine and Boufal were not injured as had been said, that maybe it was just to protect them for the World Cup.”

It remains to be seen whether those tensions linger once Morocco’s World Cup participation is over, but what appears certain is that Ounahi’s performances in Qatar will prompt a fresh wave of interest in January.

“He could have gone last summer, so it’s not really new for Angers to think about Azzedine as a potential sale,” adds Crozon. “The financial situation is not good at the moment. I’m not sure it’s so bad they have to sell in January, but maybe next summer.”

All that will become clear soon enough, but for now, it is best simply to enjoy him as he lights up the world stage, and to appreciate how far Azzedine Ounahi, the skinny kid with the number eight on his back, has already come.

“The recognition he is getting is really great,” says Bouchard. “He is a beautiful player, an elegant player, the kind of player people go to the stadium to see. I just hope he continues to amaze everyone.”

Follow Morocco vs Portugal on Sky Sports digital platforms on Saturday; kick-off 3pm

Super 6 Million Returns!

Make yourself a millionaire with Super 6. Play for free, entries by 3pm Boxing Day.

Sourse: skysports.com