Anthony Elanga was a regular presence in Manchester United’s first-team squad throughout January and could be set for a bright future at Old Trafford.

The 19-year-old forward has made nine appearances this season, eight of which have come under interim manager Ralf Rangnick, who has repeatedly shown faith in the youngster and been rewarded with goals and a series of energetic displays.

Elanga featured as a substitute in Rangnick’s first game in charge against Crystal Palace, in addition to playing the entirety of the club’s final Champions League group game against Young Boys. He went on to play in all of United’s fixtures in January and looks to have cemented himself as a firm option to be considered by the German.

Elanga appears to be another academy prospect to have successfully graduated to the first team, but exactly how has he risen to prominence at Manchester United?

- Latest Manchester United news

- Manchester United results

- Live football on Sky Sports

Starring in United’s academy

Born in 2002 and raised in Sweden, Elanga is the son of former Cameroon international Joseph Elanga, and moved to Manchester with his family in 2013. He was quickly spotted by United and joined the club’s academy, where he was deployed across the forward line during his progression through the youth teams.

Trending

- Transfer Centre LIVE! Rice, Bissouma, De Ligt latest

- Mendy faces new attempted rape charge

- Greenwood released on bail pending further investigation

- Aubameyang: My target is Champions League football

- Ismael sacked by West Brom; Maresca a contender

- Sturgeon calls for SPFL to take action on Goodwillie signing

- Papers: PL giants ready to enter Rice war

- Elanga’s rise to prominence at Man Utd

- Premier League January transfers: Club by club

- Ramsey: Why I joined Rangers on ‘nervy’ Deadline Day

- Video

- Latest News

In the 2018/19 season, Elanga scored three goals and provided five assists for the U18 side and followed this up with 10 goal involvements the following season. His performances were recognised by the club as he earned the Jimmy Murphy Young Player of the Year award, following in the footsteps of fellow academy graduate Marcus Rashford.

Image: Elanga was productive at youth level for United’s U18 and U23 teams

Elanga’s achievements in United’s youth set-up were acknowledged by manager Ole Gunnar Solskjaer, who gave the youngster his first-team debut in a pre-season friendly against Aston Villa in 2020.

Also See:

Having appeared sporadically for the U23 team during his time with the U18s, Elanga moved up permanently in the 2020/21 season and registered nine goals and three assists in 16 Premier League 2 appearances.

It was here where Elanga demonstrated his versatility as a forward. Despite being deployed as a left winger in some games and as a striker in others, he maintained his effectiveness in both positions, averaging 0.58 goals per 90 minutes.

Solskjaer: ‘The future is bright for him’

His success prompted Solskjaer to bring him into the first-team fold towards the business end of United’s 2020/21 Europa League campaign, with Elanga named as a substitute against Granada and Roma.

He remained on the bench in both games, but United’s congested fixture schedule saw Elanga make his competitive first-team debut with a call-up to the club’s starting XI for their Premier League loss against Leicester.

Despite the defeat, Elanga looked promising during his time on the pitch and attempted 18 pressures, the joint-highest in the matchday squad, along with Amad Diallo, and completed two of his three attempted dribbles.

His performance made a positive impression and, 12 days later, he started as a centre-forward in United’s 2-1 victory against Wolves in which he registered his first competitive goal for the club in the final game of the 2021/21 Premier League season.

FREE TO WATCH: Highlights from Manchester United’s win over Wolves in the Premier League

After the game, Solskjaer praised Elanga’s work ethic and humility, while making reference to his all-round game and future: “He has got some attributes that you wish for as a player, that pace, that directness.

“He is right-footed but is equally good on his left. I have not seen him score headers so that is a big bonus as well. The future is bright for him, I think, and I know, I can trust him to keep his feet on the ground and make the most of his talent.”

Champions League debutant

Elanga returned to the U23s for the early stages of this season and continued his productivity with four Premier League 2 goals in as many games to inspire the youth side to victories against Brighton, Everton, Liverpool and Blackburn.

A substitute appearance in United’s Carabao Cup loss to West Ham was Elanga’s only first-team showing under Solskjaer this term before the Norwegian’s sacking in November.

He had a short cameo in Rangnick’s first game in charge against Crystal Palace, coming on as a substitute for Rashford. Following this, the German handed the youngster his Champions League debut as he started in United’s dead-rubber group game against Young Boys, which resulted in a 1-1 draw.

Although he did not feature in the remainder of the team’s matches in 2021, Elanga was given a vote of confidence with regard to his future prospects at Old Trafford as he signed a contract extension that would keep him at the club until 2026. In a club statement, he described United as “the perfect environment to take the next step, with world-class players and coaches to learn from every day”.

Taking the next step

With the turn of the year, Elanga appears to have taken this next step, as he played in all of United’s January fixtures and started in three consecutive Premier League games ahead of Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Anthony Martial, who has since moved to Sevilla on loan.

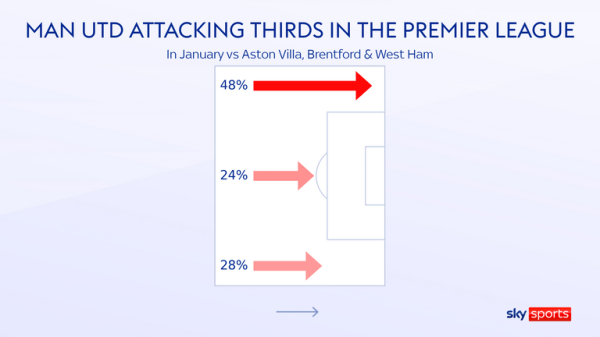

The majority of United’s offensive actions in these games have been focused on the left flank, where Elanga has started as a winger, demonstrating how he has aided the team with their attacking play.

Rangnick prefers to utilise a high-energy system with an emphasis on pressuring opposition players and Elanga appears to fulfil this brief for the manager, having contributed at least 10 pressures in each of his starts this month. This ranks him among the highest in United’s matchday squads for this statistic when he has played.

The decision to continue to play Elanga was vindicated when United faced Brentford on January 19 as he scored a brilliant improvised finish to break the deadlock for the visitors. United went on to win the game 3-1.

Elanga’s industriousness was also evident as he recorded 19 sprints at the Brentford Community Stadium – the highest of any other United player who played – while his drives into the box and dribbles in the opposition half underlined his potential to be a consistent offensive threat.

His contributions drew praise from Rangnick who said after the game that he had been “outstanding in the second half” and “put in a lot of work against the ball”.

2021/22 – a breakout year?

Elanga’s positional versatility offers Manchester United a variety of options – keeping him in wide areas would offer the club the opportunity to rest Rashford or Sancho when required. Furthermore, his ability to lead the line could similarly offer respite to Cristiano Ronaldo or Edinson Cavani, both of whom will need to be carefully managed given their respective ages.

Image: Learning from and playing alongside Cristiano Ronaldo would be an invaluable learning experience for Elanga

With the club competing for a top-four finish this season as well as a potential trophy in the FA Cup or Champions League, rotation within United’s squad will be key for Rangnick in order to continue challenging on all three fronts.

Still just 19, Elanga’s performances for Manchester United over the course of his short career have facilitated his rise to prominence. If he continues to seize the opportunity placed in front of him, and is able to maintain or improve his current form, 2021/22 could be a very productive breakout year for the youngster.

Follow Manchester United with Sky Sports

Follow every Man Utd game in the Premier League this season with our live blogs on the Sky Sports website and app, and watch match highlights for free shortly after full-time.

Want the Man Utd latest? Bookmark our Man Utd news page, check out Man Utd’s fixtures and Man Utd’s latest results, watch Man Utd goals and video, keep track of the Premier League table and see which Man Utd games are coming up live on Sky Sports.

Get all this and more – including notifications sent straight to your phone – by downloading the Sky Sports Scores app and setting Man Utd as your favourite team.

Hear the best Premier League reaction and expert analysis with the Essential Football and Gary Neville podcasts, keep up-to-date with our dedicated Transfer Centre, follow the Sky Sports social accounts on Twitter, Instagram and YouTube, and find out how to get Sky Sports.

Win £250,000 with Super 6!

Another Saturday, another chance to win £250,000 with Super 6. Play for free, entries by 3pm.

Sourse: skysports.com