This story is part of a group of stories called

Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

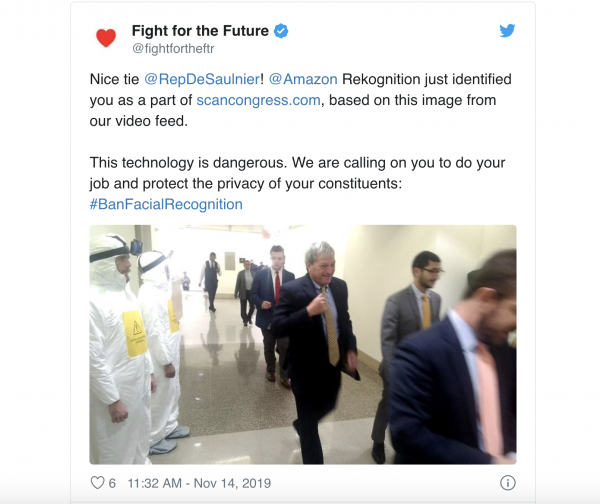

Dressed in hazmat-like jumpsuits, wearing smartphones strapped to their heads, the activists who descended upon Congress on Thursday were a strange sight.

They were there to scan faces: members of Congress, journalists, and whoever else happened to cross their path in the Capitol Hill area of Washington, DC. They also headed to K Street in hopes of finding Amazon lobbyists to scan.

Using Rekognition, Amazon’s commercially available facial recognition software, the activists scanned nearly 14,000 faces, which they cross-checked with a database that enables the people to be identified. They livestreamed the whole process.

The activists were not trying to be creepy for creepiness’s sake. Their goal was to show lawmakers that facial recognition software — which can identify an individual by analyzing their facial features in images, videos, or real time — is an invasive form of surveillance. Over the past few years, the tech has become embedded in high-stakes contexts like law enforcement and immigration; the FBI, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Customs and Border Protection, and the Transportation Security Administration all use it.

The activists have one demand: the technology should be banned.

“This should probably be illegal but until Congress takes action to ban facial recognition surveillance, it’s terrifyingly easy for anyone — a government agent, a corporation, or just a creepy stalker — to conduct biometric monitoring and violate basic rights at a massive scale,” said Evan Greer, the deputy director of Fight for the Future, the nonprofit advocacy group that organized Thursday’s action.

The Rekognition system correctly identified one lawmaker, Rep. Mark DeSaulnier of California. It also incorrectly indicated that it had identified several journalists, lobbyists, and even a celebrity — the singer Roy Orbison, who died in 1988 — thereby highlighting one of the main problems with facial recognition: Sometimes, the tech gets it wrong.

If you’re in DC, you can go to ScanCongress.com to see if your face was scanned, too.

Although the activists’ suits were emblazoned with a notice — “Facial recognition in progress” — the group did not ask people if they consent to be scanned. The software on their smartphones just automatically scanned whoever they passed as they walked around.

That sounds unethical, right? The activists agree — and that’s their point: Currently, there’s no law preventing people from scanning your face without your consent anytime you step out in public, and there should be.

“Our message for Congress is simple: make what we did today illegal,” Fight for the Future, which has been advocating for digital rights since its founding in 2011, said after the action.

“Because we’re decent human beings, all this data we’re collecting will be deleted after 2 weeks,” the group promised. “But there’s no law about that. Right now, sensitive facial recognition data can be stored forever.”

The action was part of Fight for the Future’s BanFacialRecognition.com campaign, which has been endorsed by grassroots civil rights organizations like Greenpeace and the Council on American Islamic Relations.

”People should be able to go about their daily lives without worrying that government agencies are keeping tabs on their every movement,” said Carol Rose, executive director at the ACLU of Massachusetts, in a statement on Thursday’s action. “For too long, face surveillance technology has gone unregulated, posing a serious threat to our basic civil rights and civil liberties.”

The case for banning facial recognition tech

Facial recognition software has encountered a growing backlash over the past few months. Behemoth companies like Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft have become mired in controversy over it. San Francisco, Oakland, and Somerville have all issued local bans.

Meanwhile, some of the Democratic presidential candidates have articulated how they’d handle the tech if they’re elected. In August, Sen. Bernie Sanders became the first candidate to call for a total ban on the use of facial recognition software for policing. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Sen. Kamala Harris, and former housing secretary Julián Castro have noted that they’d regulate the technology; they did not promise to ban it.

Some argue that outlawing facial recognition tech is throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater. Advocates say the software can help with worthy aims, like finding missing children and elderly adults or catching criminals and terrorists. Microsoft President Brad Smith has said it would be “cruel” to altogether stop selling the software to government agencies. This camp wants to see the tech regulated, not banned.

Yet there’s good reason to think regulation won’t be enough. The danger of this tech is not well understood by the general public, and the market for it is so lucrative that there are strong financial incentives to keep pushing it into more areas of our lives in the absence of a ban. AI is also developing so fast that regulators would likely have to play whack-a-mole as they struggle to keep up with evolving forms of facial recognition.

Then there’s the well-documented fact that human bias can creep into AI. Often, this manifests as a problem with the training data that goes into AIs: If designers mostly feed the systems examples of white male faces, and don’t think to diversify their data, the systems won’t learn to properly recognize women and people of color. And indeed, we’ve found that facial recognition systems often misidentify those groups, which could lead to them being disproportionately held for questioning when law enforcement agencies put the tech to use.

In 2015, Google’s image recognition system labeled African Americans as “gorillas.” Three years later, Rekognition wrongly matched 28 members of Congress to criminal mug shots. Another study found that three facial recognition systems — IBM, Microsoft, and China’s Megvii — were more likely to misidentify the gender of dark-skinned people (especially women) than of light-skinned people.

Even if all the technical issues were to be fixed and facial recognition tech completely de-biased, would that stop the software from harming our society when it’s deployed in the real world? Not necessarily, as a recent report from the AI Now Institute explains.

Say the tech gets just as good at identifying black people as it is at identifying white people. That may not actually be a positive change. Given that the black community is already overpoliced in the US, making black faces more legible to this tech and then giving the tech to police could just exacerbate discrimination. As Zoé Samudzi wrote at the Daily Beast, “It is not social progress to make black people equally visible to software that will inevitably be further weaponized against us.”

Woodrow Hartzog and Evan Selinger, a law professor and a philosophy professor, respectively, argued last year that facial recognition tech is inherently damaging to our social fabric. “The mere existence of facial recognition systems, which are often invisible, harms civil liberties, because people will act differently if they suspect they’re being surveilled,” they wrote. The worry is that there’ll be a chilling effect on freedom of speech, assembly, and religion.

The authors also note that our faces are something we can’t change (at least not without surgery), that they’re central to our identity, and that they’re all too easily captured from a distance (unlike fingerprints or iris scans). If we don’t ban facial recognition before it becomes more entrenched, they argue, “people won’t know what it’s like to be in public without being automatically identified, profiled, and potentially exploited.”

Luke Stark, a digital media scholar who works for Microsoft Research Montreal, made another argument for a ban in a recent article titled “Facial recognition is the plutonium of AI.”

Comparing software to a radioactive element may seem over the top, but Stark insists the analogy is apt. Plutonium is the biologically toxic element used to make atomic bombs, and just as its toxicity comes from its chemical structure, the danger of facial recognition is ineradicably, structurally embedded within it, because it attaches numerical values to the human face. He explains:

The mere fact of numerically classifying and schematizing human facial features is dangerous, he says, because it enables governments and companies to divide us into different races. It’s a short leap from having that capability to “finding numerical reasons for construing some groups as subordinate, and then reifying that subordination by wielding the ‘charisma of numbers’ to claim subordination is a ‘natural’ fact.”

In other words, racial categorization too often feeds racial discrimination. This is not a far-off hypothetical but a current reality: China is already using facial recognition to track Uighur Muslims based on their appearance, in a system the New York Times has dubbed “automated racism.” That system makes it easier for China to round up Uighurs and detain them in internment camps.

A ban is an extreme measure, yes. But a tool that enables a government to immediately identify us any time we cross the street is so inherently dangerous that treating it with extreme caution makes sense.

Instead of starting from the assumption that facial recognition is permissible — which is the de facto reality we’ve unwittingly gotten used to as tech companies marketed the software to us unencumbered by legislation — we’d do better to start from the assumption that it’s banned, then carve out rare exceptions for specific cases when it might be warranted.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Listen to Reset

The US government won’t release information about how it’s using facial recognition technology — so the ACLU is suing.

Subscribe to Reset now on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Sourse: vox.com