In 1923, a motley collection of philosophers, cultural critics, and sociologists formed the Institute of Social Research in Frankfurt, Germany. Known popularly as the Frankfurt School, it was an all-star crew of lefty theorists, including Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Erich Fromm, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse.

The Frankfurt School consisted mostly of neo-Marxists who hoped for a socialist revolution in Germany but instead got fascism in the form of the Nazi Party. Addled by their misreading of history and their failure to foresee Hitler’s rise, they developed a form of social critique known as critical theory.

Their ideas took shape when several of the critical theorists fled Nazism, landed in the US, and turned their gaze on American culture. They saw the yoke of capitalist ideology wherever they looked — in films, in radio, in poplar music, in literature. Adorno, one of the more prominent Frankfurt theorists, warned of an American “culture industry” that blurred the distinction between truth and fiction, between the commercial and the political.

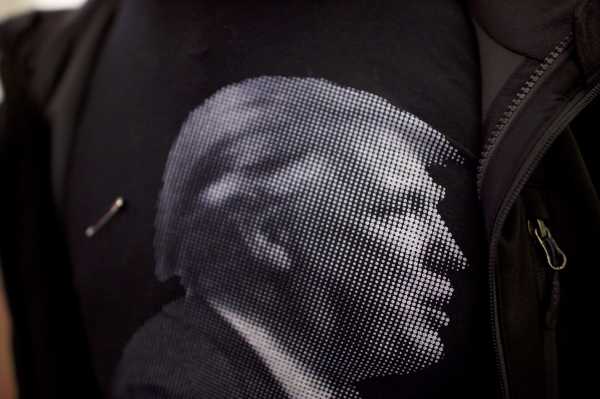

Interest in the Frankfurt School has spiked since Donald Trump burst onto the political scene in 2016. The New Yorker’s Alex Ross even penned a piece last year arguing that the Frankfurt School “knew Trump was coming.” “Trump is as much a pop-culture phenomenon as he is a political one,” Ross argued, and that’s precisely what you’d expect in age in which “traffic trumps ethics.”

If the critical theorists do make a comeback, a new book by Guardian columnist Stuart Jeffries might help lead it. A group biography of the Frankfurt intellectuals, Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School throws fresh light on a tradition of thought that feels depressingly relevant.

I spoke with Jeffries earlier this year about the book and what he learned from reentering the Frankfurt orbit. A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

What’s the main intellectual contribution of the Frankfurt School?

Stuart Jeffries

I think the main contribution is their insistence on the power of culture as a political tool, and also the power of the mass media. They examined as closely as anyone how these instruments became politically relevant, and what the consequences of that were.

Sean Illing

And how were they influenced by the rise of fascism in Germany at the time?

Stuart Jeffries

In the 1920s, they were wondering why there was no socialist revolution in a sophisticated and advanced industrialized country like Germany. Why a successful Bolshevik Revolution a couple years before in Russia but not in Germany? They concluded that culture and the use of the media was the primary tool for oppressing the masses without the masses realizing that they’re being oppressed.

This is what they witnessed in Germany, and it became the guiding insight of their work and the main source of their relevance.

Sean Illing

And yet they fell into irrelevance anyhow — why?

Stuart Jeffries

They became irrelevant because people didn’t worry too much about culture — they were too comfortable to realize there was a problem. “Culture” is a difficult concept; hard to get your hands around it.

Sean Illing

Theodor Adorno coined the phrase “culture industry.” What did he mean?

Stuart Jeffries

Well, he was distinguishing art from culture. Art is something that’s elevating and challenges the existing order, whereas culture is precisely the opposite. Culture, or the culture industry, uses art in a conservative way, which is to say it uses art to uphold the existing order.

So the culture industry peddles an ideology that supports the prevailing power structure — in the case of America, that ideology was consumerism.

Sean Illing

What changed for Adorno and the other critical theorists when they landed in America? Why did they see American culture as ripe for fascism?

Stuart Jeffries

Well, Adorno came to the states and was appalled by the culture industry; it was an utter scandal in his mind. He saw the culture industry controlling the minds of Americans in much the same way Goebbels, the Nazi propagandist, controlled the minds of Germans.

So Adorno and the other critical theorists saw culture as inherently totalitarian, and this was particularly true in America. This, of course, didn’t go over well with the public. You have these Germans coming to your country with their old attitudes and their defense of bourgeois art, and they’re critical of every aspect of American culture and regard it as an artistic wasteland.

Americans struggled with this idea that popular culture, their popular culture, could be subversive in this way. And, to be fair, many of the critical theorists didn’t get American culture, and so they undoubtedly overreached at times.

“Trump is clearly a product of a mass media age. The way he speaks and lies and bombards voters — this is a way of controlling people, especially people who don’t have a sense of history.”

Sean Illing

What was so unique about the culture industry in America? Adorno seemed to think it was a prop for totalitarian capitalism, and that it was all the more insidious because it was more camouflaged than it was in Germany.

Stuart Jeffries

He thought it was so insidious because it didn’t appear to have an ideological message; it was never self-consciously ideological in the way that German propaganda was. It wasn’t that America was equivalent to Germany or that American propaganda was equivalently awful; rather, it was that America’s culture industry smuggled its consumerist ethos into its art with a similar goal of producing conformity of thought and behavior. Having just fled Germany, Adorno saw this as a precursor to something like fascism.

Sean Illing

The goal of German propaganda at the time was obvious, but what was the goal of American propaganda? To manufacture consent by way of mass distraction?

Stuart Jeffries

Manufacturing distraction is exactly what it is. If you read Herbert Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man, you see him struggling with this problem. He sees in 1964 that everyone is getting too comfortable to revolt against oppression of any kind. People are distracted by the sexual revolution, by popular music, by virtually every aspect of mass culture.

As you can see, it’s really hard to sympathize with these guys, because they’re bringing such a sweeping critique that it’s, frankly, hard to believe. But I’m convinced there’s some truth in it.

Sean Illing

One thing I appreciate about the critical theorists was their willingness to identify totalitarian tendencies on the left and the right. They recognized that ideological single-mindedness was the real danger.

Stuart Jeffries

They were true critics in that sense, and that resonated with me as well. I used to be involved in the Communist Party, and very often the “left fascism” that Habermas, one of the more famous Frankfurt scholars, described is what I saw — the shutting down of debate in particular. While they incited hatred on both sides of the aisle, you have to admire their intellectual consistency.

Sean Illing

Why did you write this book about the Frankfurt School now? It seems strangely relevant given what’s happening in our politics at the moment, but obviously you undertook this project a few years ago when things were quite different.

Stuart Jeffries

After the economic crisis in 2008, books like Karl Marx’s Capital were suddenly best-sellers, and the reason was that people were looking for critiques of contemporary culture. So it seemed like a good time to dust these guys off and revisit their work. And then someone like Trump comes along and proves it even further.

Sean Illing

A lot of people are fumbling for constructive ways to think about what’s happening right now, both politically and culturally. I’ve watched Trump bulldoze his way to the presidency for over a year now, and I still can’t quite believe it.

Stuart Jeffries

There’s a lot of similar factors operating in the UK, where I live, and in America. You see this with Brexit and with Trump. There’s a resurgence of racism and a kind of contempt for liberal democracy.

From the perspective of critical theory, Trump is clearly a product of a mass media age. The way he speaks and lies and bombards voters — this is a way of controlling people, especially people who don’t have a sense of history. I saw the same thing in the months leading up the Brexit vote earlier this year: the lying, the fearmongering, the hysteria. Mass media allows for a kind of collective hypnosis, and to some extent that is what we’re seeing.

Sean Illing

I’ve thought a lot about what Trump’s success says about our culture — mostly how empty and decadent it is. But I wonder if that’s too easy, if I’m missing something deeper.

Stuart Jeffries

That’s interesting. I had a friend involved in Democratic politics in Pennsylvania this year, and he kept asking people if they were going to vote for Hillary, and they’d often say, “No, I can’t do it — God will decide.” I find that sense of fatalism and that failure to take one’s responsibility seriously terrifying. And yet it’s been brought to life in the most vivid way imaginable, and I have to hope that the consequences of this will force people to reengage.

“Mass media allows for a kind of collective hypnosis, and to some extent that is what we’re seeing.”

Sean Illing

It’s hard not to see Trump’s election, and really the state of discourse in general, as an indictment of our broader culture, a culture nurtured by the very instruments of control the critical theorists worried about.

Stuart Jeffries

I think things have become more heightened by mass media, but I’m not sure anything has fundamentally changed. Look, I’m doing my best to be optimistic here, but I mostly share your angst. Like the critical theorists themselves, I don’t have the solutions. That we have problem, however, is rather obvious.

Sean Illing

Here’s the thing: If Trump’s rise represented an actual substantive rebellion, that at least would suggest a revolution in consciousness. But it’s not that serious. There’s no content behind it. Trump is just a symbol of negation, a big middle finger to the establishment. He’s a TV show for a country transfixed by spectacle. And so in that sense, Trumpism is exactly what you’d expect a “revolution” in the age of mass media to look like.

Stuart Jeffries

Sadly, I agree. If you listen to Trump speak, it’s all stream-of-consciousness gibberish. There’s no real thought, no real intellectual process, no historical memory. It’s a rhetorical sham, but a kind of brilliant one when you think about it. He’s a projection of his supporters, and he knows it.

He won by capturing attention, and he captured attention by folding pop entertainment into politics, which is something the critical theorists anticipated.

Sean Illing

The Frankfurt School lost its luster decades ago. Do you see their ideas making a comeback given all these political and cultural transformations?

Stuart Jeffries

Definitely. There’s a lot to learn from the critical theorists, whatever your politics might be. They have a lot to say about modern culture, about what’s wrong with society, and about the corrupting influence of consumerism.

That alone makes them essential today.

Watch: A look back at 2016

Sourse: vox.com