Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

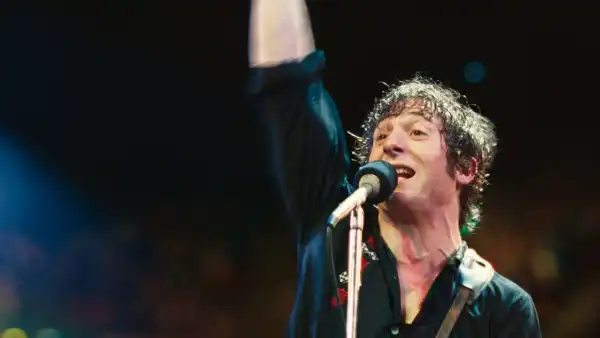

Concerning viewpoint, biographical films possess an inherent conflict. As a rule, filmmakers initiate such ventures from a place of deep respect; consequently, numerous projects swiftly transition from ardor to glorification and from storytelling to pandering to fans. A particularly acute concern arises in biographical depictions focusing on a living and still-performing celebrity, whose endorsement directors may court, as much on a personal level as on a contractual one. Scott Cooper’s biopic “Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere,” featuring Jeremy Allen White, exemplifies this tendency. While a critical exposé of the Boss is not anticipated, the film’s excessive reverence and formality render it akin to promotional material. It bears a resemblance, in its concept, to another recent biopic about a celebrated artist, Richard Linklater’s “Nouvelle Vague.” Both center on the protagonist’s creation of a specific piece of work—Springsteen’s 1982 album, “Nebraska,” and Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 picture, “Breathless,” respectively—amidst challenges to their unconventional approaches and outcomes. However, while Linklater adopts a stern stance regarding the irascible stubbornness that propelled Godard in making his initial film, Cooper emphasizes more personal facets of the musician’s narrative while only lightly touching upon them. “Springsteen” feels, predominantly, like an advertisement for what was, deliberately, the least commercially viable of Springsteen’s records.

This is all the more regrettable because the narrative elements—psychological unease, love, creative exploration, ingrained family history of pain, work-related burdens—are significant, intricate, and filled with drama. The picture commences at the close of a concert tour in 1981. Bruce (White) goes back to his residence in Colts Neck, New Jersey, where he dwells on his own, unsure of his aspirations for his next album. He is immersed in a profoundly reminiscent state, revisiting difficult moments from his younger years—primarily involving his father (Stephen Graham), who is aloof, resentful, irate, and intimidating, including to Bruce’s virtuous mother (Gaby Hoffmann). Bruce is portrayed rejuvenating his artistic energies by performing at the Stone Pony, in nearby Asbury Park, and gleaning ideas from Flannery O’Connor’s writings and in films, notably Terrence Malick’s “Badlands,” inspired by the real-life murderer Charles Starkweather, who will serve as the muse for the eponymous song on “Nebraska.” To bypass the costly undertaking of composing songs within the studio setting, Bruce procures a novel gadget, a portable multitrack cassette player, installed within his bedroom and crafts a demo independently, consisting of tracks intended for refinement and recording alongside his E Street Band. Subsequently, following his and the band’s studio takes of those songs and other prospective hits (notably “Born in the U.S.A.”), he insists on issuing the unpolished demo tape in its unaffected form, and releasing it initially. His manager, Jon (Jeremy Strong)—Springsteen’s actual manager, both then and now, Jon Landau—oversees the business dealings; he is the ultimate problem-solver, in both professional and personal capacities.

Bruce’s private affairs are in disarray. He increasingly becomes morose and reclusive, which transpire to be early indicators of despondency. He also embarks on a relationship with a woman by the name of Faye (Odessa Young), whom he encounters outside the Stone Pony. Their affection commences with an element of mutual connection, yet the dialogue presented between them is no more substantial than her naming her preferred musicians—Lou Reed, Debbie Harry, Patti Smith, and, naturally, Springsteen. There is no further elaboration regarding particulars, and scarcely any concerning their existence. Their eventual closeness is depicted in one of the most awkward intimate moments I’ve witnessed recently, as it conveys both excess and deficiency: a solitary simultaneous close-up of their countenances, in subdued illumination, that might as well be supplanted by a verified affirmation asserting “They engaged in sexual relations.” As Bruce’s struggles with melancholy intensify, Faye ultimately possesses more to communicate to him—in the screenwriters’-handbook rendition of psychological generalizations. The blandly mechanical role of this uninspired scene is to excuse Bruce’s amorous evasiveness predicated on his malady, so as to preserve a halo surrounding Bruce’s character. The film’s portrayals of the torments of depression remain polished and subdued.

A pivotal instant occurs during a cross-country vehicle journey, wherein Bruce’s chauffeur, Matt (Harrison Sloan Gilbertson), is compelled to aid a troubled Bruce in maintaining his composure at a county fair. Nevertheless, that scene, too, is expeditious, typical, and superficial; it does not so much illustrate a collapse as it does signify one. The prior glimpses into Bruce’s childhood reveal that his temperamental father likewise was afflicted with the condition, and these scenes are inevitably, if predictably, poignant, albeit Cooper resorts to the convention of exhibiting them in monochrome, generalizing them, as if a nineteen-fifties upbringing mirrored the televisions of the epoch. The superior segment resides not in the flashbacks’ substance but rather in their arrangement: Bruce repeatedly drives to the residence where he matured, which currently appears deserted, and gazes at it as if attempting to conjure up recollections. Within Warren Zanes’s 2023 tome, “Deliver Me from Nowhere,” from which the movie is adapted, Springsteen is documented as undertaking those drives and, he continued, “attending to the utterances of my father, my mother, myself as a child.” That is a decidedly more evocative and haunting account than any of the renditions within the movie.

Concerning the narrative’s essence, the crafting and distribution of “Nebraska,” “Springsteen” is concurrently inherently gripping in its configuration and abbreviated and blurred in its specifics. Scenario following scenario materializes not to observe happenings meticulously or to uncover aspects of personality but to release fragments of data that aggregate into a plot: Jon encountering an executive anticipating Bruce’s forthcoming album to achieve immense success; Bruce idly strumming his instrument and touching the facade of a collection of O’Connor’s narratives. Cooper dedicates considerably more deliberation to the conveyance of the multitrack tape system by an associate referred to as Mikey (Paul Walter Hauser) than to Bruce’s endeavors to capture his tracks with it. There exists minimal depiction of Bruce singing within his abode—merely adequate for evidentiary considerations, and not captured with any sentiment of fascination or wonder. There is no grasp of precisely what Bruce is pursuing while he is performing, how he devised each melody, how he incorporated the supplementary instrumentation (all of which he executed personally) within his impromptu personal studio. He enlists Mikey’s assistance in documenting, yet their collaborative endeavor within that pivotal procedure is omitted.

The omissions, the absence of inquisitiveness in imparting the narrative, possess significance extending beyond mere factual implications; they diminish the movie’s emotive scope—encompassing its renditions. White’s portrayal is dedicated and fluid; as an imitation, it is neither astonishing nor disconcertingly uncanny but, rather, contemplative and sincere. In juxtaposition to Timothée Chalamet’s embodiment of Bob Dylan in “A Complete Unknown,” White’s depiction of Springsteen is understated—an interpretation befitting the persona of the significantly less demonstrative Springsteen. However, White as Bruce also expresses less depth than Chalamet as Bob, not on account of his being inherently a less articulate actor but due to Cooper’s writing and direction not affording him any sufficiently expansive scenarios wherein to cultivate the character.

Bruce not merely mandates the issuance of the cassette tape’s unrefined recordings but additionally proposes exacting stipulations for the album’s unsealing (no singles, no tour, no press), and it is Jon’s function to relay this message to the record-company executives. The duo’s tie of devotion and comprehension furnishes the emotive core of the movie, yet their connection remains largely unexplored. Jon encourages Bruce to simply forge ahead and generate compositions. “Discover something authentic,” Jon implores—he will “manage the clamor.” Jon is a former music reporter and analyst, and in a scene at his residence alongside his spouse (Grace Gummer) he furnishes the movie’s scant lines of external perspective on “Nebraska.” Bruce is “channeling something profoundly intimate and somber,” Jon remarks, later adding that Bruce harbors remorse regarding stardom and abandoning the inhabitants of his home town. The movie refrains from delving further into considering the substance of the album at issue; these concise snippets of discourse encapsulate Cooper’s viewpoint concerning what the album conveys.

Cooper averts the fact that “Nebraska” is, among other facets, a political album. Its tracks are replete with laborers receiving unjust treatment—losing a position, forfeiting a mortgaged dwelling to a financial institution, owing funds, accepting employment for an outlaw, enduring the strain of a supervisor’s disapproval, being penniless and resorting to unlawful conduct, attempting to coexist with the suffering of armed service in the Vietnam Conflict. The record not solely narrates a saga of eroded confidence in the American aspiration; it proffers a reflective disparagement of the notion that the purported aspiration ever amounted to more than this. Within “Springsteen,” Bruce articulates his fondness for the demo tape’s aesthetic “from the bygone era or something.” Distant from gazing backward longingly toward the nineteen-fifties, however, “Nebraska” intimates that, within the lives of working Americans, there had perpetually existed violence and anguish lurking beneath serenely repressed surfaces—and that the pressures and burdens that he and the nation were enduring presently emanate from antiquity. Cooper’s movie assuredly does not depict Bruce’s childhood as idyllic, yet in confining Bruce’s backward-looking despondency to the individual sphere, it disregards the singer-songwriter’s broader societal vision. The movie lacks the fortitude of the genuine Springsteen’s convictions. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com