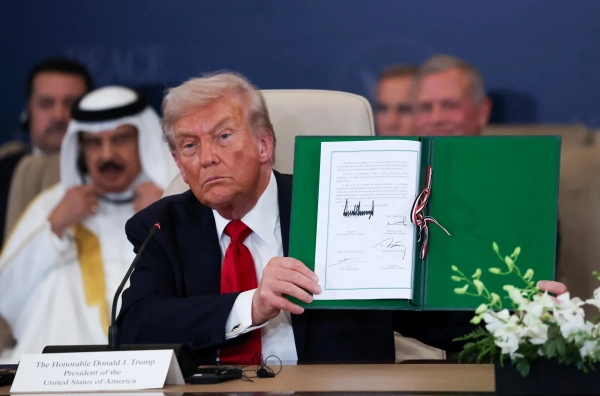

The commander-in-chief is sending masked forces into the thoroughfares of liberal cities, striving to install amenable tycoons in control of the media landscape, and endeavoring to imprison his own adversaries.

Can any democratic society rebound from such circumstances?

At the commencement of the year, two teams comprising researchers disseminated articles aiming to tackle this precise inquiry — and arrived at what seemed to be contrary conclusions.

Both articles centered on occurrences they termed “democratic U-turns,” depicting scenarios wherein a country commences as a democracy, veers toward authoritarianism, and then undergoes a swift recovery. The initial team’s findings leaned toward optimism: they pinpointed 102 U-turn instances since 1900 and deduced that, in 90 percent of these, the outcome involved “restored or even augmented degrees of democracy.” The subsequent team scrutinized 21 contemporary instances and reversed the conclusions — asserting that “close to 90 percent” of purported U-turns constituted fleeting illusions.

So, which perspective is accurate? To ascertain this, I scrutinized the foundational data and engaged in dialogue with researchers representing each team. As it transpires, the seemingly divergent discoveries possess a greater degree of consistency than initially perceived — bearing implications for the United States that are simultaneously promising and unsettling.

Insights Gleaned by Researchers Regarding “Democratic U-Turns”

Scholarly investigations into U-turns derive from a repository known as V-Dem, extensively regarded as the benchmark for quantitative assessments of global democracy. V-Dem operates by enlisting an expansive cohort of specialists on specific countries to furnish numerical evaluations concerning diverse facets of that nation’s democratic framework (for instance, the extent of press autonomy or the impartiality of election administration). These assessments are subsequently transmuted into composite scores, gauging the overall democratic status of a country.

The foremost team of researchers, those holding a more sanguine viewpoint, is headquartered at the institute responsible for compiling and disseminating the V-Dem database. Upon examining their own data, authors Marina Nord, Fabio Angiolillo, Martin Lundstedt, Felix Wiebrecht, and Staffan I. Lindberg discerned that U-turns — characterized as a nation’s democracy score initiating an ascent subsequent to a recent slump — are exceedingly prevalent. Exceeding half of all nations encountering a descent toward autocracy subsequently undergo a U-turn. Moreover, these U-turns commonly prove efficacious, thus substantiating the key discovery that 90 percent of U-turns witness a nation reverting to its prior democratic standing, or even surpassing it.

To comprehensively grasp the tangible manifestation of a U-turn, an examination of Poland’s recent historical trajectory proves beneficial. Once lauded as one of the most robust post-communist democracies, the right-leaning PiS government, elected in 2015, transformed the nation’s public broadcasting entity into a propaganda apparatus and populated the judicial system with its favored associates. However, in 2023, a partnership comprising opposition factions defeated PiS in national parliamentary elections and commenced efforts to reverse the incurred damage. Poland’s V-Dem score vividly illustrates the quintessential U-shaped curve — a decline during the PiS tenure, succeeded by an upswing following its ouster.

Yet this remains a recent phenomenon, and Poland has yet to reinstate its pre-PiS democratic structure. Moreover, the sustainability of its advancement in the right direction remains uncertain. The novel coalition has encountered considerable obstacles in rectifying the damage inflicted by PiS, and this year witnessed a narrow defeat in the presidential election against the PiS candidate.

The subsequent article posits that such an inability to solidify enduring progress would be more commonplace than not.

Its authors — Nic Cheeseman, Jennifer Cyr, and Mattías Bianchi — also leverage V-Dem data, concentrating their analysis on instances of democratic U-turns arising post-1994. Twenty-one instances (extracted from the original 102) conformed to these stipulations. Subsequently, the authors scrutinized the number of nations effectively upholding their elevated democracy scores following the U-turn — scrutinizing the developments transpiring in the years succeeding the initial paper’s analytical timeframe, to ascertain whether the gains accrued from a U-turn exhibited durability.

The outcomes proved discouraging. Within a five-year span following the ostensibly triumphant U-turn, 19 of the 21 nations underwent a subsequent decline in their democracy scores. Furthermore, the track record of the two exceptions, Malawi and Mali, lacked distinction.

“Malawi sustained a steady, albeit modest, degree of democracy throughout the initial five years post-U-turn; however, it reverted to a non-democratic state in the sixth year,” the authors noted. “Mali’s advancement has proven even less promising. The nation maintained a state of stable democracy, though marginally so, for a duration of five years. Nevertheless, by the sixth year, it too had transitioned into a non-democratic entity, enduring two coups in 2020 and 2021.”

Insights From the Papers About Contemporary Democracy

Marina Nord and Nic Cheeseman, researchers affiliated with the primary and secondary teams, respectively, both underscored during telephone exchanges that they did not perceive their discoveries as fundamentally conflicting. In point of fact, Cheeseman divulged, both factions were engaged in ongoing communication and deliberating potential collaborative endeavors.

This scenario deviates from the typical academic disputes, which (according to my observation) frequently devolve into triviality and acrimony. Moreover, it mirrors the notion that the two papers might represent complementary facets of a singular premise.

Both scholars concur that contemporary autocratization diverges from historical precedents. Prior to the 1990s, democracies were generally deposed via coups or revolutions — unambiguous instances of force that terminated existing regimes and supplanted them with overt authoritarian governance.

Presently, owing largely to democracy’s progressively dominant ideological standing globally, the threat tends to manifest in a more subtle and concealed manner — a phenomenon scholars term “democratic backsliding.” In such scenarios, a legitimately elected administration amends the regulations and tenets of the political framework to procure progressively unjust advantages in forthcoming elections. The ultimate objective frequently involves establishing a “competitive authoritarian” system, wherein elections are not openly manipulated, but transpire under circumstances so inequitable that they cannot legitimately be deemed democratic. This epitomizes the actions undertaken by Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party in Hungary, and the intentions of PiS in Poland.

Related

- It happened there: how democracy died in Hungary

Given that democratic backsliding transpires through legal and political maneuvers, rather than at gunpoint, its adversaries possess a greater arsenal of options (including legal proceedings, legislative obstruction, and electoral challenges) for disrupting its progression. This factor may elucidate why the initial team discerned that attempts at authoritarianism were, in actuality, more prone to culminating in a U-turn during the post-1994 epoch (73 percent of cases) compared to the aggregate historical sample (52 percent).

However, concurrently, any individual setback for authoritarian forces may prove less enduring.

Since elected authoritarians were, by definition, elected, they frequently embody a legitimate constituency within the nation’s political sphere. This support base often possesses sufficient magnitude to render it 1) unattainable for their rivals to achieve a conclusive defeat and 2) democratically impermissible for said rivals to proscribe them outright. Consequently, even if ousted through electoral means, the prospect remains that a future election could witness a victory by an individual representing that constituency, precipitating a renewed endeavor to consolidate authority.

This engenders a provisional synthesis between the two papers: that contemporary initiatives to dismantle democracy typically falter in the immediate term, yet frequently pave the way for successive attempts in due course.

“The mere existence of a democracy does not automatically guarantee its evolution into a stable democracy,” Nord elucidates, encapsulating the shared viewpoints.

Relevance for America’s Prospects

In 2013, political scientist Dan Slater introduced the concept of “democratic careening” to delineate this pattern of volatility. Careening democracies, according to Slater’s definition, are “struggling but not collapsing”: they exist within an environment characterized by “endemic unsettledness and rapid ricocheting” between seemingly disparate governing models. Such a democracy “may be liable to ‘capsize,’ or tip over temporarily so that democracy ceases to function for a limited time — but not to vanish from the democratic ranks entirely through a restoration and consolidation of authoritarian rule.”

The recent papers imply that Slater’s insights were prescient: in the ensuing decade since the publication of his work, the circumstances he portrays may be gaining greater prominence.

And at present, this characterization appears to align rather closely with the United States.

I have previously contended that, despite President Donald Trump’s formulation of an increasingly coherent blueprint for dismantling American democracy, he faces formidable impediments — encompassing federalism, widespread public skepticism, a free press, and an impartial judiciary. Research suggests that numerous nations with fewer effective bulwarks against autocratization have successfully resisted initiatives akin to Trump’s, offering a measure of optimism that the prevailing circumstances do not signify the demise of American democracy.

“I don’t think the US is beyond the point of no return,” Cheeseman tells me.

Related

- This is how Trump ends democracy

However, even should America undergo a U-turn following Trump’s departure, the nation’s challenges will not necessarily be resolved. The forces responsible for Trump’s ascendancy in the first instance will persist, susceptible to exploitation by any political figure possessing the requisite acumen and unscrupulousness.

“There is a reason why Trump came to power, and there is a reason why he won those elections,” Nord says. “If you don’t solve the underlying reasons, then of course democracy will still be at risk.”

Source: vox.com