Multiple federal courts are fighting over Louisiana’s illegal racial gerrymander.

Anti-gerrymandering protesters outside of the Supreme Court’s building. Evelyn Hockstein/Washington Post via Getty Images Ian Millhiser is a senior correspondent at Vox, where he focuses on the Supreme Court, the Constitution, and the decline of liberal democracy in the United States. He received a JD from Duke University and is the author of two books on the Supreme Court.

Three different federal courts are fighting among themselves over who gets to draw Louisiana’s congressional maps.

In June 2022, Chief Judge Shelly Dick, an Obama appointee to the United States District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana, ruled that the state’s maps were an illegal racial gerrymander. Under the invalidated maps, Black voters made up a majority in only one of six congressional districts, despite the fact that Black people comprise about one-third of the state’s population.

Dick concluded that “the appropriate remedy in this context is a remedial congressional redistricting plan that includes an additional majority-Black congressional district” — meaning that the state needed new maps with at least two Black-majority districts.

vox-mark

Sign up for the newsletter SCOTUS, Explained

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Email (required)

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Notice. You can opt out at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply. For more newsletters, check out our newsletters page. Subscribe

There’s been a lot of litigation since Dick initially made this decision, but the most significant recent development in this case, known as Robinson v. Ardoin, came last November. That’s when a bipartisan panel of the Fifth Circuit, the federal appeals court that oversees Louisiana, rejected many of the state’s legal arguments against Dick’s decision, but also gave the state until mid-January to draw new, legal maps before Dick could step in and draw them herself.

The state legislature took the Fifth Circuit up on this offer and passed a new law drawing maps that included two Black-majority districts. So it seemed like that would be the end of the litigation over Louisiana’s maps.

But then an entirely different set of plaintiffs filed a new lawsuit in a different court, the Western District of Louisiana, claiming that the new maps were unconstitutional. This second case is known as Callais v. Landry.

For complicated procedural reasons, Callais was heard by a panel of three judges, and two of those judges — the ones appointed by Donald Trump — agreed that the new maps are illegal.

That means that Louisiana is now subject to two competing court orders. Judge Dick’s order prohibits it from using its old maps, and the Western District’s order prohibits it from using the new maps. Meanwhile, the state needs to hold a congressional election this year, and it must have maps of some kind to do that.

This mess is now before the Supreme Court in a pair of cases known as Robinson v. Callais and Landry v. Callais. In these cases, both the plaintiffs in Robinson and the state ask the justices to put the lower court’s decision in Callais on hold, although for different reasons. If the justices don’t step in, it’s far from clear how, exactly, Louisiana is supposed to conduct its congressional election.

What does the law actually say about Louisiana’s congressional maps?

There’s no question that Louisiana’s original maps, the ones struck down by Judge Dick, are illegal.

Dick initially ruled that those maps were illegal in mid-2022, but the Supreme Court stepped in almost immediately to put that decision on hold. At the time, the justices were also considering a very similar case, Allen v. Milligan, which involved a racially gerrymandered map in Alabama. The Court ultimately concluded that Alabama’s maps were an illegal racial gerrymander and ordered the state to redraw those maps to include an additional Black-majority district.

Shortly after it handed down its Milligan decision, it lifted its hold on the Robinson litigation, allowing that challenge to Louisiana’s original maps to move forward. There’s been a lot of needless drama since that happened, but the Fifth Circuit ultimately rejected Louisiana’s arguments seeking to salvage its original maps, pointing out that “most of the arguments the State made here were addressed and rejected by the Supreme Court in Milligan.”

The Fifth Circuit gave the state legislature until mid-January to draw new maps that include a second Black-majority district, and the legislature complied.

The two judges who struck down these new maps in the Callais case, meanwhile, fixated on a line in Milligan that states that a key provision of the Voting Rights Act “never requires adoption of districts that violate traditional redistricting principles” — such as ensuring that districts are compact and that they group together communities with similar interests.

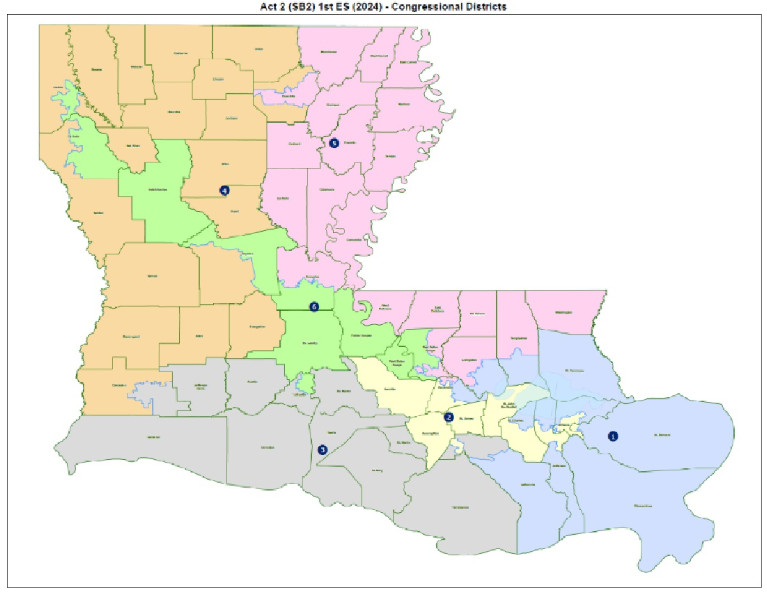

The new maps are pretty ugly, and they include at least one district that snakes through the center of the state, flouting traditional norms of compactness.

The most recent congressional maps drawn by the Louisiana state legislature. Plaintiff’s complaint in Callais v. Landry

The reason for these oddly shaped districts is that Louisiana’s Republican legislature hoped to accomplish two goals when it drew these new maps. It knew that it must include two Black-majority districts to comply with Judge Dick’s order in the Robinson case, but it also wanted to ensure that three Republican incumbents — Speaker Mike Johnson, House Majority Leader Steve Scalise, and Rep. Julia Letlow — would still prevail under the new maps.

Additionally, the Robinson plaintiffs claim that the state legislature wanted to ensure that the new Black-majority district would come at the expense of Rep. Garret Graves (R-LA), who they describe as a “political rival” of Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry (R).

In any event, the two judges behind the Callais decision ultimately concluded that these new maps were too ugly to survive, ruling them invalid in large part because they do not “comply with traditional districting principles.”

It’s far from clear that this decision was correct. Though Milligan did say that the Voting Rights Act does not require districts that violate these traditional principles, that line appeared in a broader paragraph emphasizing that “reapportionment remains primarily the duty and responsibility of the States, not the federal courts.”

Read in context, in other words, the key line in Milligan that the Callais judges fixated upon suggests that a state legislature ordered to draw new maps under the Voting Rights Act should retain the freedom to comply with traditional principles such as drawing compact districts, not they they absolutely must do so.

But there’s also no need for the Supreme Court to untangle this complicated debate about what Milligan means, at least not right now, because there’s another perfectly good reason why the Callais judges’ decision blocking the new maps must be put on hold.

The “Purcell principle,” briefly explained

In Purcell v. Gonzales (2006), the Supreme Court warned that “federal courts ordinarily should not alter state election rules in the period close to an election.” The Court has often wielded this principle quite aggressively — too aggressively, I’ve argued — in cases where a lower court issued a decision in an election year that could benefit the Democratic Party.

In the Milligan case, for example, Justice Brett Kavanaugh relied on Purcell to argue that Alabama could not be ordered to redraw its maps more than nine months before a general election. That meant that Alabama got to run the 2022 election using illegal maps that the Supreme Court eventually struck down, and it also meant that Republicans won an extra seat in the current, closely divided US House of Representatives.

But, if Purcell was violated when a federal court ordered Alabama to redraw its maps in the January before a congressional election, then it was certainly violated in Callais, where a lower court ordered Louisiana to redraw its maps in late April of an election year.

In its brief asking the Supreme Court to block the lower court’s decision in Callais, Louisiana’s lawyers argue that “this case screams for a Purcell stay,” pointing to a long line of deadlines the state’s election officials must comply with — the first deadline is this Wednesday — for the state’s congressional election to comply with state law.

Even if a federal court were to delay those deadlines, moreover, the late-breaking Callais decision means that candidates for congressional seats in Louisiana now have no idea who their constituents are and where they should campaign for the 2024 election. They won’t know that until the courts stop messing around and tell them which maps the state must use in its next election.

The two judges behind the Callais decision, meanwhile, are threatening to draw their own map if the state legislature does not produce a new map by June 4. But there’s no guarantee that the Callais judges’ map will comply with Judge Dick’s order in the Robinson litigation — which could potentially lead to an awkward situation where Judge Dick has to strike down maps drawn by her fellow judges.

None of this confusion makes any sense, and there is an easy way to solve it, at least for now. The Supreme Court should block the lower court’s decision in Callais for violating the Purcell principle. And it should order the state to use the new, legislatively drawn maps in the 2024 election.

All of the more difficult questions about whether those maps are too ugly to be used in future elections can be resolved by the Supreme Court at a later date.

Sourse: vox.com