The justices will decide whether to ban mifepristone, a drug used in half of US abortions.

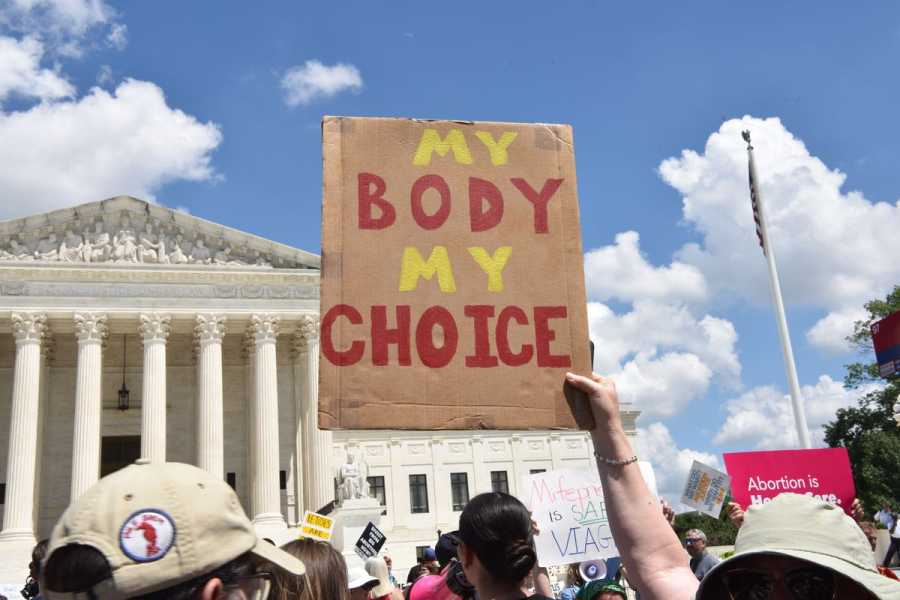

Abortion rights activists march to the Supreme Court on June 24, 2023, in Washington, DC. The rally was held to mark the one-year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion. Sha Hanting/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images Ian Millhiser is a senior correspondent at Vox, where he focuses on the Supreme Court, the Constitution, and the decline of liberal democracy in the United States. He received a JD from Duke University and is the author of two books on the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court announced on Wednesday that it will give a full hearing to a long-simmering dispute over whether far-right federal courts may ban the abortion drug mifepristone.

Mifepristone is part of a two-drug treatment that causes the uterus to expel pregnancy tissue. This two-drug regime, which may be taken up to the 70th day of a pregnancy, is often a safer alternative than surgical abortion — and it is also a less invasive procedure. More than half of all US abortions are medication abortions, which use mifepristone.

The Court’s decision to hear two consolidated cases, known as FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine and Danco Laboratories v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, is unsurprising, as it has already weighed in on this case once. And the Court’s previous actions suggest that most of the justices are unlikely to allow a court-imposed mifepristone ban to stand.

But while the Court seems likely to decide that judges shouldn’t be allowed to upend the nationwide availability of a common drug, the fact that these cases are once again before the Court is a reminder of just how broken the federal judiciary is.

In April 2023, federal Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk — a Trump appointee closely affiliated with the Christian right and a longtime crusader against abortion, birth control, and many forms of human sexuality — attempted to ban mifepristone by suspending its regulatory approval. The Supreme Court halted Kacsmaryk’s order and determined that the medication, which has been legal in the United States since 2000, should remain lawful while this case worked its way through the appellate process.

Nevertheless, Kacsmaryk’s decision was appealed to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, a far-right court dominated by MAGA stalwarts, and a panel of that court also voted to heavily restrict mifepristone in August 2023 (though that decision never took effect because of the Supreme Court’s previous intervention in this case).

Technically, the Fifth Circuit’s decision did not ban mifepristone outright — it merely required the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to unravel several changes the FDA made to the protocol health providers must use when prescribing the drug, which rolled out in 2016. As a practical matter, however, requiring health providers to return to pre-2016 protocols would prevent them from prescribing mifepristone for at least several months, because the drug’s manufacturer would need to revise its labels, recertify providers on the new, court-imposed protocol, and take other steps that cannot be completed quickly.

As the conservative Supreme Court’s April order suggests, the legal arguments against mifepristone are exceedingly weak. No federal court, including Kacsmaryk’s court, had jurisdiction to hear this case in the first place. And the law gives the FDA, and not judges, the power to decide which drugs should be available in the US.

It does so, moreover, for a very good reason. The FDA is made up of scientists and other experts in drug safety and efficacy, while the courts are made up of lawyers who rarely know anything about these subjects.

One other sign that the justices probably aren’t going to ban mifepristone is that, at the same time that the Court announced it would hear the two Alliance cases, it also denied a request by the anti-abortion plaintiffs in those cases. Those plaintiffs asked the justices to consider reinstating Kacsmaryk’s sweeping ban on mifepristone. In refusing to even consider that option, the Court effectively takes it off the table — at least for now.

Yet, while the law is clear, the stakes in the Alliance cases are exceedingly high. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), the Court’s decision overruling Roe v. Wade, the five justices in the majority pledged to stay out of national abortion policy — announcing that “it is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

The Alliance cases will tell us if that was all a big lie, and if the same justices are willing to rely on the flimsiest of pretexts to ban a medication used in most US abortions.

The plaintiffs’ legal arguments in Alliance are absurdly weak

It’s hard to overstate how clear-cut of a case this should be for defenders of mifepristone. As Adam Unikowsky, a former law clerk to the late conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, wrote in a lengthy takedown of the mifepristone litigation, “If the subject matter of this case were anything other than abortion, the plaintiffs would have no chance of succeeding in the Supreme Court.”

For starters, no federal court should have heard this case in the first place. That’s because the Constitution requires plaintiffs in federal lawsuits to have “standing,” which means that a plaintiff challenging a federal policy must show that they’ve been injured in some way by that policy. And none of the plaintiffs in the Alliance cases are harmed in any legally significant way by the fact that mifepristone has been legal for nearly a quarter of a century.

The Alliance plaintiffs are doctors who oppose abortion, and organizations representing doctors who oppose abortion. They claim that they are injured by the fact that mifepristone is legal because a patient who takes that drug might experience a complication that might require follow-up treatment (serious complications from mifepristone are quite rare).

Rather then returning to their abortion provider for follow-up care, this patient then might seek care instead from one of the plaintiff doctors or a member of one of the plaintiff organizations. That might require that doctor to divert attention from other patients. Or the plaintiff doctor might have to provide care to this patient that the doctor finds morally objectionable.

That’s a whole lot of mights. And it is far too many mights to allow this lawsuit to proceed. The Supreme Court held in Clapper v. Amnesty Int’l USA (2013) that a plaintiff can sometimes file a federal lawsuit because they fear they will experience some kind of injury in the future, but only if “the threatened injury is certainly impending.” But there is no certainty here, just a long chain of speculative events that could, possibly, lead to some unidentified doctor doing something they find objectionable at some point in the future.

Meanwhile, even if Kacsmaryk or the Fifth Circuit were permitted to hear this lawsuit, they are not permitted to second-guess the FDA’s scientific judgments about which drugs are sufficiently safe and effective to be prescribed in the US.

As the Supreme Court held in FCC v. Prometheus Radio Project (2021), when a federal agency exercises the authority granted to it by Congress — and there’s no question that the FDA has the authority to decide which drugs are safe and effective — “a court may not substitute its own policy judgment for that of the agency.” Rather, the judiciary’s job is simply to determine that the FDA has “reasonably considered the relevant issues and reasonably explained the decision” to authorize a particular drug.

There’s no serious question that the FDA cleared this low bar — which is intentionally set very low because, again, scientists working at the FDA know a whole lot more than judges do about drug safety, and are more likely to make sensible decisions than black-robed lawyers.

When the FDA first approved mifepristone in 2000, it had already been legal in France for 12 years, so the FDA was able to rely on a dozen years of data showing that the two-drug medication abortion protocol, which uses another drug called misoprostol in sequence with mifepristone, effectively terminated pregnancies in at least 95 percent of cases, and that the side effects were typically mild.

Subsequent studies, which the FDA also considered in its 2016 decision to relax restrictions previously imposed on mifepristone, confirmed that the drug is safe and effective. A 2013 report, for example, looked at 87 different studies, which included data from about 45,000 different patients who had medication abortions. It confirmed that the two-drug protocol effectively ends pregnancy in 95 percent of cases, and that serious complications such as vaginal bleeding or infection occurred in only 3 out of 1,000 patients.

This is more than enough evidence to justify the FDA’s decision to approve, and later to relax restrictions, on mifepristone. And the judges who have second-guessed these decisions have done so based on uninformed speculation about what else the FDA could have done to ensure that the drug is safe.

The Fifth Circuit, for example, struck down the FDA’s decision to relax several restrictions on mifepristone at once in 2016 because, while the FDA did consider studies justifying each of these changes, “none of the studies it relied on examined the effect of implementing all those changes together.”

But, again, the law does not require the FDA to conduct, or to get someone else to conduct, a single study that confirms the conclusion that FDA was able to reach by looking at multiple studies in conjunction. All that it requires is that the FDA reasonably considers the case for and against approving a particular drug protocol, and that it reasonably explains why it reached a particular conclusion.

The federal judiciary’s process for filtering out meritless cases is broken

The federal judiciary is a three-tiered system. Most cases are initially filed in a federal district court, where a single trial judge presides over the case and eventually reaches a decision. That decision can then be appealed to an intermediate federal appeals court, where it is normally heard by a panel of three judges.

Parties that lose in a federal court of appeal can then seek review from the Supreme Court, but such review is rarely granted. The Supreme Court typically hears about 60-80 of the over 8,000 cases annually brought by petitioners asking the Court to give their case a full review.

One reason why the justices hear so few cases is that the lower courts are supposed to act as filters, weeding out relatively easy cases where the law decidedly favors one party or the other, and leaving the hardest cases — typically, the ones that are sufficiently difficult that they divide lower court judges — for the nation’s highest Court.

But this system has broken down, and it is particularly broken in Texas’s federal courts. Those courts frequently allow plaintiffs to choose which trial judge will hear their case by filing the lawsuit in a geographic region that has only one federal judge. One hundred percent of all cases filed in Amarillo, Texas, are assigned to Kacsmaryk, for example; a fact that has led legions of religious conservatives to file their cases in Amarillo. Then, once Kacsmaryk gets his hands on these cases, he generally responds with dubiously reasoned opinions attacking abortion, birth control, and LGBTQ people.

After such a litigant obtains a court order from their hand-picked Texas judge, that decision appeals to the Fifth Circuit, with its array of MAGA judges. Indeed, the Fifth Circuit routinely hands down decisions so extreme, even compared to the preferences of the current, GOP-dominated Supreme Court, that a significant percentage of the Court’s merits docket is now consumed by Fifth Circuit decisions seeking to sabotage the Biden administration or implement a Republican policy.

This term, for example, the justices are expected to reverse a Fifth Circuit decision that declared an entire federal agency, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, unconstitutional. The Court is expected to reverse the Fifth Circuit’s decision that people subject to domestic violence restraining orders have a constitutional right to own a gun. And the Court appears likely to limit, if not reverse in its entirety, a Fifth Circuit decision that would have destroyed the federal government’s ability to enforce the laws protecting investors from fraud.

When all is said and done, the Supreme Court is also likely to reverse the Fifth Circuit’s decision in the Alliance cases and reaffirm the rule that experts in the FDA, and not black-robed lawyers who know nothing about medicine or biology, should decide which medications may be prescribed in the United States.

But the fact that the federal judiciary’s process for filtering out meritless cases has broken down places an unfortunate burden on the justices themselves, and it places an unconscionable burden on litigants. The makers of mifepristone have now had to deal with the uncertainty and the expense of litigating this completely meritless case for more than a year. They had to do so, moreover, in three different courts — including two separate trips to the Supreme Court.

And the only reason this case wasn’t dismissed months ago is because the plaintiffs were able to hand-pick a judge who appears incapable of distinguishing between what the law actually says, and what a fringe group of religious conservatives wish that it said.

Sourse: vox.com