The inaugural issue of Interview magazine, published in late 1969, billed itself as a “Monthly Film Journal.” The Warhol superstar Viva reclined on the cover—her nude body formed an “H” shape with those of Gerome Ragni and James Rado, the writers of “Hair.” Peering over the ménage is Agnès Varda, framing a shot from her film “Lions Love.” The words “Andy Warhol’s” don’t appear above the title, as they would in some later editions, but you can sense Warhol’s self-mythologizing in the type along the bottom: FIRST ISSUE COLLECTOR’S EDITION.

Warhol would later downplay the magazine, saying that he started it to get into parties, or to “give Brigid something to do”—meaning Brigid Berlin, another of his superstars. Yet another, Jackie Curtis, wrote an advice column in the early issues, which Warhol would hand out to acquaintances. What Interview became, over the decades, was unmistakably Warholian: a celebrity magazine as art object, in which fame was the raw material. Famous people, by virtue of being famous—or declaring themselves so—were inherently interesting, so why not recruit them into the art of conversation? The magazine’s patented celebrity-on-celebrity dialogues compounded the formula, like mixing colors on a palette. Instead of a journalist to interview Jack Nicholson, get Julian Schnabel. (For the results, see the April, 2003, issue.)

If you tend to blame celebrity culture run amok for our current national woes, you might find some poetry in this week’s news that Interview would fold, bankrupt, just short of its fiftieth year—mired in lawsuits over unpaid work and rampant infighting. But mostly it’s just a bummer, like hearing about an East Village punk den shutting its doors—even though you may not have stopped in for the last decade or so. At Slate, Felix Salmon suggested that the Andy Warhol Foundation buy the magazine back from Peter Brant, the art collector and entrepreneur who (along with his then wife, Sandra) bought Interview soon after Warhol’s death.

Barring that, or some other deus ex machina, there’s plenty to mourn. Under editors like Bob Colacello and Ingrid Sischy, Interview, nicknamed “The Crystal Ball of Pop,” chronicled several decades of cool—or, more accurately, filtered whoever was floating around in the culture through its own prism of cool. Like everything Warhol touched, it could turn mass culture into counterculture, and vice versa, just by squinting. The tape recorder (which Warhol called “my wife”) was always on, fashioning one-act plays out of casual conversations—the journalistic answer to found art. Visually, the magazine owes as much to the artist and scenester Richard F. Bernstein as it does to Warhol. From 1972 through the late eighties, Bernstein created dozens of cover portraits, painting over photographs of stars with jazzy pastels. “He makes everyone look so famous,” Warhol once said of Bernstein, who died in 2002, of complications from AIDS. To scroll through his covers—Brooke Shields, Tom Cruise, Madonna, Grace Jones—is to get a whiff of nostalgia as evocative as a roller disco.

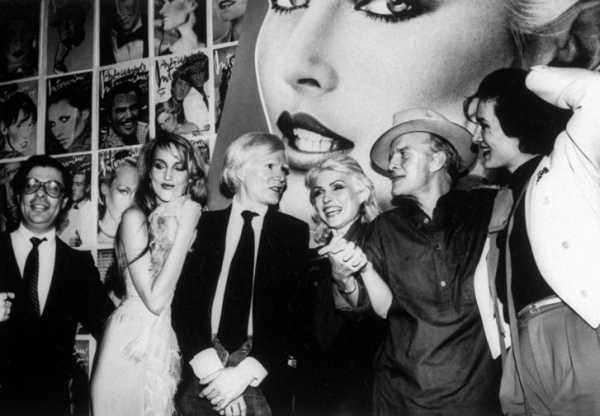

Bob Colacello, Jerry Hall, Andy Warhol, Debbie Harry, Truman Capote, and Paloma Picasso at a Studio 54 party for Interview magazine, celebrating Harry’s cover appearance.

Photograph by Robin Platzer / The LIFE Images Collection / Getty

As it happens, I have three of them on my mantel. I got them a few years ago off of eBay and framed them: three Interview issues from 1987 and 1988, featuring Bernstein covers of Eddie Murphy, Divine, and Anjelica Huston. I’d like to think that Warhol would approve of my using his magazine as design objects—and, let’s face it, taste signifiers—but the truth is that they always fill me with longing for a certain brand of avant-garde glamour, just out of reach. Even so, I had not cracked one open until yesterday. I went for the middle one (Divine), removed the frame, and spent the afternoon reading the issue of February, 1988.

Any magazine back issue is a time capsule of sorts, but this Interview gave me the exact dose of 1988 that I wanted. Amid ads for Calvin Klein, “La Bamba,” and Absolut Peppar, there are black-and-white portraits of the young Bill Paxton and Tracy Pollan, a portfolio of up-and-coming Latin musicians, a T. Coraghessan Boyle story, and excerpts from the journals of Stephen Tennant. (“I am a devotee of the dusk—a supplicant of the twilight.”) And, of course, there are interviews. Steven Zeller talks to Michael Crawford, the star of “The Phantom of the Opera,” newly opened on Broadway. Kevin Sessums interviews the French actress Carole Bouquet, who had just replaced Catherine Deneuve as the face of Chanel No. 5. (“You hate bullshit, don’t you?” “Yeah, I really hate it.”) There are touches that feel almost ridiculously eighties, as in Guy D. Garcia’s scene-setting for an interview with Dodi Fayed, then thirty-two and best known for producing “Chariots of Fire”: “Besides his several cars, a corporate plane, jet helicopter and yacht, Fayed owns homes in London and Malibu (where he’s just a hell’s throw from Sting’s spread).” Meanwhile, at the Beverly Hills Hotel, Tom Wolfe (in his “ice cream-white custom suit”) answers questions about “The Bonfire of the Vanities,” which had just been published, after being serialized in Rolling Stone. “Luckily,” he says, “magazines are not eternal, they’re thrown away, so I didn’t have to worry about my mistakes.”

The interview with Divine is, of course, divine. Promoting his role in John Waters’s “Hairspray,” he talks about teaching the mash potato to his co-star Ricki Lake (“She’s 19 and delightful. I hate her”); his taste in movies (“I love blood and guts and tear-it-ups and shoot-outs. I never miss a Stallone film”); and Bette Midler telling Barbara Walters that she was “the first Divine” (“I wanted to punch her right in the face”). When the interviewer, Hal Rubenstein, brings up dieting, it’s poignant to remember that Divine died a month later, of an enlarged heart:

HR: With the current mania for thinness, are people less tolerant of people with weight problems?

D: Yes. No one has patience with fat people. They think we’re

disgusting hogs. It’s very difficult to watch your weight when you’re

on the road so much, eating in restaurants every night. I can’t

exactly sit there and set up my scale and calorie counter. The chef

doesn’t want to hear about it.

HR: But there are certain foods you should stay away from altogether, like cream, red meat, sugar.

D: Sugar? Really?

HR: Divine! Are you kidding?

D: Well, I really don’t like sweets, except for ice cream. What about

salt?

HR: Salt makes you retain water.

D: But I love salt and spicy food.

HR: But spicy will make you crave sweet.

D: Well, don’t tell me I can’t have pasta.

HR: No. Pasta is good. Just keep away from cream sauces.

D: But that’s what makes it fun.

The eeriest passage—as quintessentially 1988 as it is 2018—comes during John Heilpern’s interview with Kathleen Tynan, who had just published a book about her late husband, Kenneth Tynan. She and Heilpern had met at a book party in her honor, thrown by Tina Brown, with guests including Joan Didion, Diane Sawyer, and Susan Sontag. “I have to tell you, I was the only person there whose name I didn’t know,” Heilpern says.

Tynan responds, “It was impressive. My friend Phyllis Newman said that as she walked in, a stranger came up to her, thrust out his hand and said, ‘May I introduce myself. I’m Donald Trump.’ She said later, ‘I knew then he was running for office.’ ”

Sourse: newyorker.com