I walked to the mailbox and pulled out a sheaf of envelopes that included a letter from Philip Roth. I was twenty-nine and pregnant. I had written a book but assumed that no one would read it—and, anyway, I was preoccupied with three older children, a passel of miserable cats, barn spiders in the eaves of the house, and a pot of rice. I set down the pile of mail and didn’t open the letter. Assuming that it was an invitation to join a famous person for a cause or a favorite charity, I forgot about it.

As it turned out, the envelope contained a bona fide letter of appreciation from Philip Roth, a response to a story of mine that The Atlantic had just published, “Saint Marie.”

The day before, I’d bought a bag of shrimp that cost eight dollars. I had never spent that much money on an item of food. I had just stirred the shrimp into the pot of hot buttered rice when I opened the letter. I put the lid on the pot and tried to understand what I was reading. I was reading a letter from Philip Roth. He had typed it out and signed his name. It did not seem forged. I read the letter over and over.

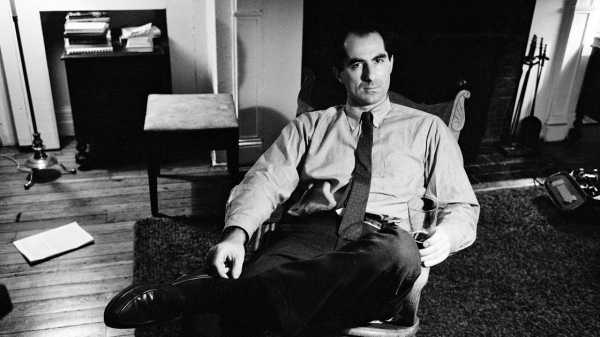

Roth’s earliest works were fearless and fearlessly funny—then came the subtler beauty of “The Ghost Writer.” His work had struck down self-consciousness for me. I would write what I would write.

My guests, intimidating faculty from Dartmouth, arrived. When I took the lid off the pot, the shrimp had dissolved into the rice. Someone asked what the dish was called, and I said, “Mexican shrimp and rice.”

“Where’s the shrimp?” the professor said.

I pointed at some faint pink specks.

I had a letter from Philip Roth. He had taken the time to write. I felt that things might change.

That letter is somewhere in my accumulated stacks of paper. He also sent a quote for my novel “Love Medicine,” which I keep in a cardboard folder on my desk. For years, I occasionally saw Philip and Claire, then, after their divorce, just Philip. Life had thrown him around. Famously thrown him around. I had landed hard, too. It was a relief to talk to someone who made the worst stuff funny. We started talking more often, on the phone. Conversation with Philip was sometimes like being grilled by a precocious child. He zeroed in on something he didn’t know and would not stop asking questions. He wanted to know everything about Native-owned casinos, about tribal law, tribal citizenship, history. What it was like to grow up in North Dakota. Eventually, I gave him a book list, cautioning him to read it slowly so that he wouldn’t get depressed. “All right, Louise of the Dark Knowledge,” he answered. I never made a list for myself of the books he was reading, because they were so monumental—historical series that required intense and sustained concentration. I knew I couldn’t manage that, yet. Maybe once I was not living on the school calendar. Anyway, he showed me the way to age: read your way up the mountain. He was becoming ever more brilliant.

Last February, my daughter Kiizh and I visited Philip. He wrote down what I was reading—“Nomadland,” by Jessica Bruder. He was trying to understand what had happened to our country. I wish he had lived to see someone better in the White House. We got to talking about his early years. He described his first apartment in New York, a basement apartment. As he wrote, people walked by constantly. He could see their feet from his desk. Back and forth. And he had a cat, which would sit on his manuscript. I found it hard to believe that he’d had a cat. Suddenly, Philip pointed out that, when you get to a certain age, people see you and the first thing they say is “You look great!”

“I know,” I said. “It means you’re getting old.”

“That’s exactly what it means,” he said.

“You look great.”

“You look great, too.”

“The only one here who really looks great is Kiizh,” I said.

“How old are you, Kiizh?”

“Seventeen.”

Philip looked at me, dumbstruck. I looked back at him, also dumbstruck. For once, he had no questions. There really wasn’t anything to say. Seventeen! Kiizh is good at silence. After a while, he gathered himself.

“What are you reading?” he asked her.

“ ‘Huck Finn.’ ”

He smiled the most wonderful, euphoric smile.

“Oh! To read ‘Huckleberry Finn’ for the first time!”

“Really, it’s ‘Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,’ ” Kiizh said.

“Seventeen. And already a copy editor!”

Sourse: newyorker.com