Democrats, eying a potential blue wave in November, have Georgia on their minds.

It would be a stretch to call Georgia a swing state, but in a sign of the shifting sands of American politics, Hillary Clinton came closer to winning it in 2016 than she did to carrying Ohio or Iowa. Donald Trump’s 50 percent share of the vote was underwhelming. Combined with term limits forcing out the incumbent Republican governor and the natural tendency of midterm elections to swing against the president’s party, it’s given Democrats hope of electing a governor there for the first time since Roy Barnes won in 1998.

A gubernatorial victory could be a big deal after the 2020 census. It would give Democrats a hand in redrawing electoral maps that currently give Republicans 10 out of 14 House seats. And it would put them within striking distance of two-thirds supermajorities in the state legislature, even though both Clinton and Obama drew 45 percent of the vote.

Democratic hopes are so high for Tuesday’s primary, in fact, that not one but two solid candidates have entered the race for the Democratic nomination, giving the party an unusually vigorously contested primary for statewide office.

The battle lines between the two contenders, Stacey Abrams and Stacey Evans, are a little fuzzy in policy terms but do implicate many of the ideological, ethnic, and factional clashes ongoing inside the party.

This Democratic primary has attracted the lion’s share of the national press attention so far, along with some recent notice of GOP contender Michael Williams’s idea of touring the state with a “deportation bus.” In reality, Williams is a bit player in a GOP primary. He likely won’t make it to the runoff election on July 24, and the Republican nomination will likely be won by either incumbent Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle or incumbent Secretary of State Brian Kemp.

And while Democratic hopes for a victory are hardly impossible, it’s still more likely than not that the GOP will prevail in November. Nonetheless, Georgia does have one of the smallest non-Hispanic white population shares in the country. So if — and it’s a big if — Democrats can seriously engage and mobilize the state’s minority voters while capitalizing on Trump’s relative unpopularity in the more upscale Atlantic suburbs, they could not only pull off a win but devise a longer-term template for electoral success throughout the Southeast.

Here’s what you need to know.

A tale of two Staceys

Stacey Abrams, a former minority leader of the Georgia House of Representatives who would be the first African-American woman elected governor of any US state, jumped into the race early on the Democratic side. She has more or less been the frontrunner from the get-go.

She’s challenged by Stacey Evans, a Georgia House of Representatives member and attorney, in a race that’s somewhat difficult to characterize. Internet political junkies’ first introduction to the matchup often came from the Intercept’s Zaid Jilani, a left-wing Georgian whose main angle on the race is the idea that Abrams is a fake progressive.

The substance of the ideological disagreement between Abrams and Evans comes down to their different handling of an initiative by Gov. Nathan Deal that cut spending on the state’s popular HOPE Scholarship program back during a recession-induced budget crisis.

This dispute has several ins and outs, but the basic shape of things is that Deal proposed swinging cuts to the program that once guaranteed free in-state tuition to any Georgia high school graduate who maintained at least a B average. Abrams cut a deal with Deal that reduced the extent of the cuts but still pared back the program substantially. Evans stood strong in opposition.

Jilani, in an article published almost a year ago, argued that this left Evans “poised to draw her contrast around an issue that has galvanized progressives nationally, and one that led to a bitter feud among Democrats in Georgia just a few years ago: free college,” though he also conceded that the disagreement “is as much about tactics as it is about ideology.”

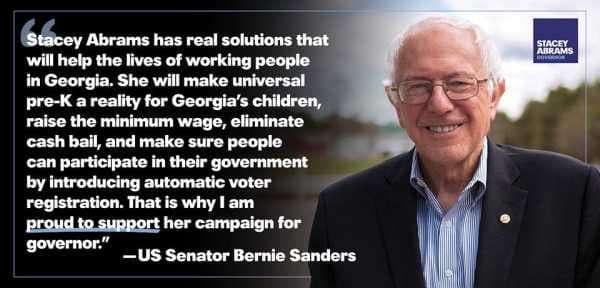

And, indeed, though a left-versus-establishment proxy war would be a convenient story for out-of-state journalists to cover, Bernie Sanders and his political organization Our Revolution are both supporting Abrams for governor, as have Sens. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Kamala Harris (D-CA).

Evans, by contrast, is supported by former Gov. Barnes and former Sen. Max Cleland. This makes the race seem more like a rerun of the Virginia gubernatorial primary between Tom Perriello and Ralph Northam, which largely pit Perriello-loving national political figures against the state party establishment. But Abrams is endorsed by three of the four Georgia Democrats serving in the US House of Representatives (the fourth one has not endorsed) and a bevy of state legislators.

At the simplest level, then, the main pattern is that Abrams is black — as are Booker and Harris and the House Democrats backing her. Evans is white, as are Cleland and Barnes. The tried-and-true formula for a Democrat winning a statewide election in the South, to the extent that one exists, is to nominate a white face to lead a mostly black party and hope to win over white swing voters that way. Nominating Abrams would be to take a different, arguably more modern but also arguably less tested, approach.

That said, even this is too simple. Evans does have African-American supporters, including former state Sen. Vincent Fort, precisely because Abrams’s stewardship of the Georgia House minority really was contentious within the state party, even if national leaders don’t seem too interested.

There is not, however, a ton of concrete disagreement between Evans and Abrams on anything — including the HOPE scholarships. Both candidates pledge to increase the minimum wage; expand Medicaid; fund HOPE, investment in education, and clean energy, etc.; and both would, in practice, struggle to get progressive ideas enacted in the face of what is overwhelmingly likely to be a GOP-controlled legislature.

The available polling suggests that Abrams is in the lead, though there are a large number of undecided voters. Plus, turnout modeling for Democratic primaries in Georgia is an inexact science.

Cagle versus Kemp versus others

The race on the GOP side, meanwhile, has more of a clear structure to it.

The frontrunner, Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle, leads in the polls and fundraising and is running very much as outgoing Gov. Nathan Deal’s natural successor and the leader of the mainstream business-oriented wing of the Georgia Republican Party. Secretary of State Brian Kemp, meanwhile, is trying to catch him with broadly Trumpy tactics, including a buzzy ad in which he points a shotgun at a young man putatively interested in dating his daughter.

In policy terms, there is not a ton of daylight between Cagle and Kemp, though Kemp has generally tried to portray himself to the right of Cagle. After Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant signed a 15-week abortion ban, for example, both Kemp and Cagle spoke in support of similar measures and touted their anti-abortion credentials, but Cagle specifically called for even stricter legislation and vowed to “sign the toughest abortion laws in the country as your next governor.”

The real policy meat comes from the lesser candidates, former state Sen. Hunter Hill and state Sen. Michael Williams, both of whom say they favor abolishing the state’s income tax and allowing people to carry concealed firearms without a permit.

Cagle has a clear lead in the polls, but it’s not entirely clear that he will secure the 50 percent he needs to avoid a runoff. It’s at least conceivable that in a runoff scenario, Kemp could pick up enough support from the lesser candidates to prevail.

Onward to November

The Democratic primary has attracted more attention and is in most respects more thematically interesting.

But realistically, either nominee would be an underdog. Early trial heat polling has Cagle beating either Evans or Abrams, though the fact that he’s well below 50 percent in those polls shows that Democrats have a shot.

But the surge of optimism about Democratic prospects in Georgia may be based on an erroneous assumption. In the immediate wake of the 2016 election, it was often believed that Democrats’ best hopes for electoral gains came in purply parts of the country that had swung away from Trump — places, in other words, that Trump may have won but where he did distinctly worse than Mitt Romney.

That was the kind of thinking that led grassroots activists to plow vast sums of money into John Ossoff’s campaign in the special election for Georgia’s Sixth Congressional District in the Atlanta suburbs, and it’s basically the thinking behind optimism about Georgia as a whole.

In practice, however, while Democrats have done a good job with consolidating ground that Clinton won from Trump (as seen in Democrats strong performance in northern Virginia state legislative races in November 2017), they haven’t necessarily made any additional gains in these areas.

Instead, Republicans seem to have given back at least some of Trump’s gains with Northern working-class whites, as he’s turned out to conform his economic policy agenda much more closely to conservative orthodoxy than his campaign rhetoric implied. Morning Consult’s state-by-state Trump approval tracking polls, for example, show him as more popular in Georgia than in Iowa or Ohio even though the 2016 election outcome was the reverse of that.

Still, Democrats have been persistently within striking distance in Georgia and have certainly won some longer-shot elections in the Trump era.

Sourse: vox.com