In the mid-nineteen-nineties, Koushun Takami was dozing on his futon on the island of Shikoku, Japan, when he was visited by an apparition: a maniacal schoolteacher addressing a group of students. “All right, class, listen up,” Takami heard the teacher say. “Today, I’m going to have you all kill each other.” Takami was in his twenties, and he had recently quit his job as a reporter for a local newspaper to become a novelist. As a literature student at Osaka University, he had started and abandoned several horror-infused detective stories. But the well had long since run dry; he had left his job with neither a plan nor a plot in mind. The visitation wasn’t a haunting; it was an epiphany.

In the novel that followed, an instructor sends forty-two junior high schoolers to a deserted island. The kids awaken to find explosive collars secured around their necks. They’re ordered to collect a backpack containing a map and a random weapon: a gun or an icepick, if they’re lucky, a paper fan or a shamisen banjo if they’re not. The students must compete to become the last person standing. The winner will leave the island with a lifetime pension; if there is more than one survivor, the collars will detonate. Some of the students choose suicide over submission. Most, eventually, comply and fight.

Takami was a fan of professional wrestling. He particularly enjoyed matches that involved wrestlers who made fleeting, mutually beneficial alliances, a style traditionally known as battle royal. There could be only one winner in a battle royal, so pacts were inevitably broken, lending each match a wary frisson. Takami saw a similar dynamic in adolescence, when friendships were easily formed and revoked. Forcing a group of classmates to destroy one another was provocative, but also strangely relatable. When he told a friend that he planned to call the book “Battle Royal,” his friend, confusing the term with a coffee drink, café royale, replied, “You mean ‘Battle Royale’?”

The novel proved controversial. In 1997, the judges of a Japanese writing prize passed on the manuscript, because it was too reminiscent of a recent murder, in Kobe, in which a fourteen-year-old boy impaled the head of another student on the gates of a school. But, in 1999, Ohta Publishing, a company known for provocative titles (it later published the memoir of the Kobe killer), released the book. It became an international best-seller; Stephen King named it to his summer reading list. In 2000, “Battle Royale” became a hit movie, starring Takeshi Kitano as the schoolteacher. Quentin Tarantino later called it one of his favorite films of all time.

Takami’s premise was well suited to video-game adaptation. The rules were clearly defined, the setting neatly contained, and competitive violence had been one of the medium’s primary currencies since the nineteen-sixties. Video-game technology, however, wasn’t quite up to par. In the early two-thousands, very few computers could simulate, in 3-D, the behavior of dozens of characters doing battle across an island, and very few Internet providers could calculate whether a banjo hurled by, say, Bob, in Kansas, would strike the head of Sven, in Stockholm.

Soon, though, such games would be more than possible: they would transform the industry. In 2020, Warzone, the Call of Duty series’ take on “Battle Royale,” attracted more than a hundred million active players, generating revenues of about three billion. The same year, Epic Games reported that Fortnite, its candy-colored, kid-friendly spin on “Battle Royale,” had three hundred and fifty million accounts—more than the population of the United States. (A recent lawsuit revealed that, when Fortnite was available on Apple devices, the game generated an estimated seven hundred million in App Store revenue.) Today, countless games, along with hit TV shows such as “Squid Game,” bear the stamp of “Battle Royale” ’s influence. Takami’s blueprint, drawn from a dream, has become one of the dominant paradigms in entertainment.

The story of that rise might begin in 2013, in Brazil, where Brendan Greene, an Irish Web designer, was living while saving up for a plane ticket home, following a divorce. Greene, who is assiduously private (his online moniker is PlayerUnknown), grew up on the Curragh Camp, an army training center in County Kildare, where his father served. He and his brothers played on the family’s Atari 2600 console “until it fell apart,” he told me, but he later fell out of love with games, which he felt were becoming too scripted—more like movies than the tests of skill and cunning he enjoyed. In Brazil, Greene was browsing Reddit when he read about DayZ, a punishing, survival-based video game that appealed to his desire for challenge. It was the first game he bought in years, and he quickly became obsessed.

DayZ was a mod, a new game built from the parts of an old one—in this case, a military-combat simulator called Arma 2. Mods, which are usually made by amateur enthusiasts, can be arcane and scrappy, but the scene is a hotbed for experimentation. DayZ’s game play fascinated Greene, who, despite lacking technical expertise, began to make his own mods to the mod. He added a fortress in the middle of the map; players would enter empty-handed, scavenge for weapons, then fight to the death. Unlike most competitive video games at the time, in which characters respawned after dying, Greene’s mod radically gave each player a single life. When you were out, you were out.

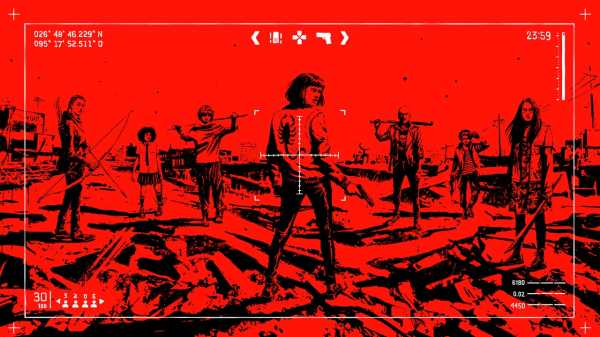

The rules evoked “The Hunger Games,” a series of books that share a similar premise to “Battle Royale.” (The series’ author, Suzanne Collins, has insisted that she was unaware of Takami’s work when she wrote the books). One of Greene’s collaborators suggested the title “Hunger Gamez,” but Greene had worked long enough in marketing to know he was “going to get sued if we did that,” he told me. While studying fine art in Dublin, Greene had watched “Battle Royale.” Recalling the film’s poster, which showed two schoolchildren, one holding an axe, the other a shotgun, he mocked up an image that placed his game’s character in a similar pose, alongside the text “DayZ: Battle Royale.”

Greene drew further inspiration from the film. He replaced his game’s fortress with a barn, and arranged twenty-four backpacks at its far end, each containing a grenade, a pistol, a bandage, or a chainsaw. At the beginning of a match, which lasted ninety minutes, the players arrived at one end of the barn. “If you were smart, you didn’t give a fuck about the backpacks and you just ran,” Greene told me. “But new players would rush forward. Someone would get the gun. Then everyone would be screaming.”

In Takami’s novel, portions of the island become off limits at regular intervals, forcing the classmates into smaller spaces. Greene wanted a similar way to narrow the field. Dividing the island into squares was beyond his programming ability, so he placed a tightening circle onto the map; if a player wandered outside it, their character would quickly expire. Each match now enjoyed a natural, exhilarating crescendo.

DayZ: Battle Royale went online in September, 2013. The game used six servers, which Greene managed by hand; he stayed awake for forty-eight hours at a time, acting as a virtual bouncer, allowing new players in and locking the room when it was full. An obscure nook of the Web became a coveted hangout. “People were waiting for hours, even days, to get in,” he recalled. Saqib Ali Zahid, a popular American video-game streamer known as Lirik, was an early player. “He kept coming back for one more game,” Greene said. “A guy of discerning taste like that . . . I was onto something.”

Greene’s mod soon caught the attention of industry professionals. On Twitter, he received a message from John Smedley, the then president of Sony Online Entertainment, who invited him to San Diego to design a battle-royale mode for H1Z1, a game in development. “Here was an opportunity to get my game in front of a global audience,” Greene told me. He joined as a consultant, but left after finding that the H1Z1 team had simplified his vision. Several other companies had become interested in making battle-royale games, and Greene worried that his idea was being wrested from his control. “I was, like, ‘Hello?’ ” he said.

In 2016, Greene received an e-mail from Changhan Kim, a game developer from South Korea, offering him the chance to make a battle royale to his specifications. That March, the day before his fortieth birthday, Greene immigrated to South Korea, and a year later his team released PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, or PUBG. PUBG was based closely on Greene’s original mod, with a few elegant adjustments: a hundred players would now enter the map by jumping from a plane, allowing each to choose whether to head toward a popular area, for immediate tussling, or toward a more remote spot, to scavenge. The game was an immediate blockbuster, earning eleven million dollars in three days. In 2018, it passed a billion in sales.

To read or watch a battle royale is an intense experience. But to participate in one involves a different tier of exhilaration, which flings one between states of anguish and euphoria. The sense of being at once hunter and prey feels primal. The first time I played PUBG, I forced my character to crouch in his underpants in a bush, hypervigilant for the sound of approaching footsteps. Eventually, having secured a shotgun and a few improving attachments, I trembled my way to the top of a hill, where I lay nauseous with adrenaline. After a while, another player stepped on my character. A brisk fusillade later, I was out.

“Often, in multiplayer games, you’re just running around, racking up points,” Frank Lantz, the founding director of the New York University Game Center, told me. “That works well, but it has a samey intensity, like a piece of music that starts out fast and stays fast. Battle royale has a built-in structure and dramatic arc.” In 2021, Lantz released a Scrabble-themed battle-royale game called Babble Royale, which he co-designed with his son. “In game design, you’re always looking for rules that interact in particularly interesting ways,” he told me. A battle royale’s steadily reducing map heightens a game’s intensity, and the fact that each player has a single life raises the stakes, making each victory unforgettable. “Every action matters,” the professional Call of Duty player Ben Perkin told me. “The closer you get to the end, the more invested you become on staying alive, for that rush of a win.”

Video games broadly fall into two categories: those which, like sports, emphasize competition, and those which, like films, emphasize storytelling. Battle royale is a rare harmonious combination, a mode that encourages both dynamic, dramatic vignettes and high-stakes rivalry. At Infinity Ward, the Los Angeles-based co-developer of the Call of Duty series, which has long established the template for online competitive shooting games, PUBG was disruptive and divisive. “You could see it propagating through the office like wildfire,” Joe Cecot, the studio’s multiplayer-design director, said. “People were, like, ‘How do we make something like this? What would our twist on this be?’ ”

Introducing battle royale to a marquee series was a major risk. Call of Duty’s dominant mode had been Team Deathmatch, where two teams compete across small, carefully engineered environments, and where players can reënter the field a few moments after they’re eliminated. Battle royale, with its meandering combat and vast map, required a profound redesign. The team got to work on a new mode called Warzone, assigning six designers to build a large-scale environment using the game’s existing engine. (They loosely based the map on the Ukrainian city of Donetsk.) In order to introduce bullet drop-off over long distances, they rewrote the game’s ballistics system, and in the process realized that the series had sped up over the years, with characters running at about fifty miles per hour. In Warzone, this made it nearly impossible to hit a moving target at range. The animators installed a line of L.E.D. lights in the studio, which would trigger in sequence to show the speed at which characters ran; after attempting to race the lights, they reduced the top speed by twenty per cent, causing some on the team to balk. “One designer said to me, ‘Congratulations, you have ruined this game,’ ” Infinity Ward’s studio head, Patrick Kelly, told me.

The team also played with the established template. “We felt that battle royale was a bit too punishing,” Kelly said. “The fact you can randomly get shot in the head encourages players to hide until the herd is culled. That brutality promotes conservatism over action.” Inspired by a popular in-house mode, Kelly suggested that they introduce a kind of purgatory: eliminated players would be sent to a “gulag,” where they would take part in a one-on-one match against another loser, with the victor returning to action. This, too, was contentious. “We heard, ‘This is not battle royale—this is terrible,’ ” Kelly said.

The anxiety that Warzone would ruin the Call of Duty franchise was intense. One afternoon, Kelly was so preoccupied while driving home from the office that he ran into a stop sign, crashing his car. But when Warzone launched, in March, 2020, it became an immediate success, with more than six million downloads in twenty-four hours. “It was a transcendent moment,” Joel Emslie, the studio’s art director, told me. “It completely reënergized the franchise. Now the sky is the limit.”

One of battle royale’s virtues is its legibility: any onlooker can understand what’s happening, which is often not true with video games. On YouTube, the channel TopWARZONEMoments posts a daily twenty-minute-long highlight reel showing skilled or amusing moments of play. Within hours, each video attracts tens of thousands of views.

In the past, this straightforward voyeurism has occasionally been paired with political critique. Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” begins with a battle royale: a group of young Black men are blindfolded, then forced to fight in a basement for the amusement of drunk, wealthy white professionals. Even Takami’s book, though less overtly symbolic, uses the game to question the status quo. The novel takes place in a world where Japan won the Second World War, emerged as a Fascist power, and brutally suppressed any rebels; the battle royale is a military program meant to seed fear in the country’s youth. But Takami also targets the lure of conformity. His mother lived through the Second World War, and she told him that, though many citizens opposed Japan’s involvement, they feared the danger of protesting. “Even if a rule is clearly ridiculous, nobody will speak out against it,” he wrote later. In the novel, most of the students acquiesce to the game’s rules.

In the video-game medium, where players prize novelty—and, typically, not social commentary—the key to battle royale’s future may lie not in tweaking its rules but in deepening its story. In November, Activision released Warzone 2.0, which introduces some new mechanics. There’s now more than one safe circle, so players are herded into pockets of refuge, and it’s possible to interrogate downed opponents, making them reveal the position of their teammates. These embellishments add subtle points of difference, but it’s unlikely that they’ll energize the form. “Battle royale will now always be a part of the tool kit, in the same way that we’re never not going to have the fifty-two-card deck,” Lantz said. “But there’s not a lot of people making new games for the fifty-two-card deck. When a thirteen-year-old hears that there’s a new battle-royale game coming out today, it’s already a little bit boring. Like, you know, boomer stuff.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com