NEW YORK — For decades, Jackie Young had been searching.

Orphaned as an infant, he spent the first few years of his life in a Nazi internment camp in what is now the Czech Republic. After World War II he was taken to England, adopted and given a new name.

As an adult, he struggled to learn of his origins and his family. He had some scant information about his birth mother, who died in a concentration camp. But about his father? Nothing. Just a blank space on a birth certificate.

That changed earlier this year when genealogists used a DNA sample to help find a name — and some relatives he never knew he had.

Having that answer to a lifelong question has been “amazing," said Young, now 80 and living in London. It “opened the door that I thought would never get opened."

Now there's an effort underway to bring that possibility to other Holocaust survivors and their children.

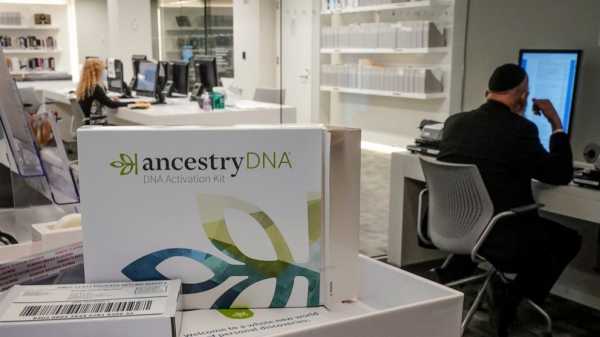

The New York-based Center for Jewish History is launching the DNA Reunion Project, offering DNA testing kits for free through an application on its website. For those who use the kits it is also offering a chance to get some guidance on next steps from the genealogists who worked with Young.

Those genealogists, Jennifer Mendelsohn and Adina Newman, have been doing this kind of work over the last several years, and run a Facebook group about Jewish DNA and genetic genealogy.

The advent of DNA technology has opened up a new world of possibilities in addition to the paper trails and archives that Holocaust survivors and their descendants have used to learn about family connections severed by genocide, Newman said.

“There are times when people are separated and they don’t even realize they’re separated. Maybe a name change occurred so they didn’t know to look for the other person," she said. “There are cases that simply cannot be solved without DNA."

While interest in genealogy and family trees is widespread, there's a particular poignancy in doing this work in a community where so many family ties have been ripped apart because of the Holocaust, Mendelsohn said.

Her earliest effort in this arena was for her husband's grandmother, who lost both parents, six siblings and a grandfather in the genocide. That effort led to aunts and cousins about whom no one in her husband's family had known.

Her husband's uncle, she said, called afterwards and said, “You know, I’ve never seen a photograph of my grandmother. Now that I see photographs of her sisters, it’s so comforting to me. I can imagine what she look like.”

“How do you explain why that’s powerful? It just is. People had nothing. Their families were erased. And now we can bring them back a little bit,” Mendelsohn said.

She and Newman take pains to emphasize that there are no guarantees. Doing the testing or searching archives doesn't mean living relatives or new information will be found. But it offers a chance.

They and the center are encouraging people to take that chance, especially as time passes and the number of living survivors declines.

“It really is the last moment where these survivors can be given some modicum of justice," said Gavriel Rosenfeld, president of the center.

“We feel the urgency of this," Newman said. “I wanted to start yesterday, and that’s why it’s like, no time like the present."

Rosenfeld said the center had allocated an initial $40,000 for the DNA kits in this beginning pilot effort and expects to spend as much as $100,000 on them in the program's first year. He said they would look to scale up further if they see enough interest.

Ken Engel thinks there will be. He leads a group in Minnesota for the children of Holocaust survivors and has already told his membership about the program.

"This is an important effort," Engel said. “It may reveal and disclose wonderful information for them that they never knew about, may make them feel more settled or more connected to the past."

Young definitely feels that way.

“I’ve been wanting to know all my life," he said. “If I hadn’t known what I do know now, I think I would still felt that my left arm or my right arm wasn’t fully formed. Family is everything, it’s the major pillar of life in humanity."

———

This story has been corrected to reflect that the initial allocation for the pilot program is $40,000, not $15,000.

Sourse: abcnews.go.com