Earlier this month, Bob Dylan released “The Philosophy of Modern Song,” a nimble, Surrealist compendium of sixty-six songs, detailing their existential weight and, on occasion, explaining what a given track might mean or do. The book reminded me, at times, of the liner notes to Harry Smith’s “Anthology of American Folk Music,” in which Smith cannily summarizes each song’s narrative arc as though it were a newspaper headline. (The entry for Chubby Parker’s “King Kong Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O,” a novelty song about a frog and a mouse getting hitched, reads, “ZOOLOGIC MISCEGENY ACHIEVED IN MOUSE-FROG NUPTIALS, RELATIVES APPROVE.”) Dylan is less literal and more prone to allegorical second-person screeds. Of Uncle Dave Macon’s “Keep My Skillet Good and Greasy,” first recorded for Vocalion Records in 1924, he writes, “In this song your self-identities are interlocked, every one of you is a dead ringer for the other. . . . You’re unmuzzled and unleashed, nightwalkin’ up the crooked way, the Royal Road, stealing turkey legs and anything sweet and spicy, roaming through the tobacco fields like Robin Hood, broiling and braising everything in sight.”

Dylan has always had a vaguely tense relationship with the writers and journalists who frantically parse his songs for meaning, and, while reading “The Philosophy of Modern Song,” there were moments when I grew slightly red-faced, worried that the book might be an elaborate gag, poking fun at all the drooling critics who have gone berserk trying to illustrate the heft and beauty of his work. (Who among us has not mixed a metaphor once or twice?) Yet the syntax and rhythm of his descriptions will be intimately familiar to anyone who listened to “Theme Time Radio Hour,” the Sirius XM show that Dylan hosted from 2006 to 2009. Ultimately, both projects reiterate, in a serious way, just how difficult it is to dissect, probe, and evaluate something as ineffable and brain-scrambling as popular music. On occasion, late at night, hunched over my stereo, ice cubes clinking around a rocks glass, I like to deliver punchy, Dylan-style soliloquies to myself, espousing the spiritual significance of, say, Missy Elliott’s “Work It,” or Joanna Newsom’s “Sapokanikan,” or Stevie Nicks’s “Edge of Seventeen”: “A secret to be decoded, written in a foreign tongue, tucked into an eyeglass’s case, delivered to an open window at half past midnight, by a snowy owl with a crooked blue eye,” I’ll rasp at no one. Dylan’s descriptions are tone poems, intricate evocations of a certain mood or sensation. He is extremely interested in the devastations that connect us. In one of the book’s more eloquent and emotional pieces, on John Trudell’s “Doesn’t Hurt Anymore”—Trudell’s pregnant wife, three children, and mother-in-law were killed in a suspicious house fire in 1979, on the Duck Valley Indian Reservation, in Montana—he writes that what ultimately unites people “is suffering and suffering only.” Dylan understands that the most important thing about a song—maybe the most important thing about living—is how it makes you feel. Sometimes putting that feeling down on paper is impossible to do without getting a little weird. The final entry in the book is on “Where or When,” a hit for Dion and the Belmonts in 1959. “And when Dion’s voice bursts through for a solo moment on the bridge, it captures that moment of shimmering persistence of memory in a way the printed word can only hint at,” Dylan writes.

The premise of “The Philosophy of Modern Song” was to pick a finite number of songs—for Dylan to define the canon that defined him—and he did so without equivocation. (“No matter how many chairs you have, you only have one ass,” he reminds us.) Much like Smith’s “Anthology,” Dylan’s book is deeply personal, despite its sweeping title. To be fair, taste should be idiosyncratic and kind of awkward. (I’m reminded of this every time Barack Obama releases another exquisitely curated and artfully inclusive list of his favorite books or records—yes, yes, lovely, but what do you really like, when no one else is looking, when the critics aren’t keeping score?) It’s obvious that Dylan did not tweak his preferences to suit a cultural narrative or to minimize his age, despite apparently being aware(!) of the smirking gibe “O.K., boomer”: in the essay on Charlie Poole’s “Old and Only in the Way” he writes, “Way before taunts of ‘Okay, boomer’ and the calling of people with experience the pejorative term ‘olds,’ this country has had a tendency to isolate the grizzled dotard, if not on an ice floe than in retirement camps where they could gum pudding and play bingo away from the delicate eyes of youth.”

Yet that the book contains only four songs performed by women—let that sink in!—is both grim and astounding. This might lead readers to question Dylan’s character and, more worrying, to wonder about the limits of his musical knowledge. Even if it were possible to hotfoot around the lack of women (and it is hard to find a way to understand the void as satirical), his essay on Johnnie Taylor’s “Cheaper to Keep Her” is peppered with odd, doddering declarations: a married couple with no children is “not a family. . . . They are just two friends; friends with benefits and insurance coverage but just friends nonetheless.” He goes on to argue for polygamy, and wonders if a “downtrodden woman with no future, battered around by the whims of a cruel society” would be “better off as one of a rich man’s wives—taken care of properly, rather than friendless on the street depending on government stamps?” Is this a joke? Does it matter?

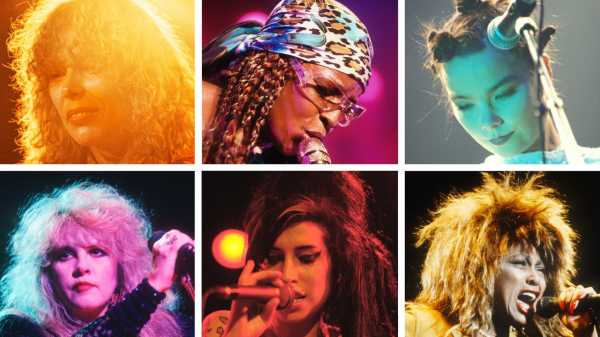

And so in the spirit of revision and reappropriation and hubris, which is to say in the spirit of folk music, I took a stab at making a companion piece to “The Philosophy of Modern Song”: my own list of formative records that have skewed my perception. They are presented here in no order, and without annotation. Not all of these songs were written by their respective performers, but all of the performances are extraordinary. I had a little help from my friend, editor, and staff Dylanologist, David Remnick. (Like Dylan in the book’s acknowledgments, I also want to sincerely thank “all the crew at Dunkin’ Donuts” for helping to fuel this enterprise.)

Joni Mitchell, “A Case of You”

Björk, “Army of Me”

Mary J. Blige, “Family Affair”

Missy Elliott, “Work It”

Aretha Franklin, “Amazing Grace”

Bessie Smith, “Down Hearted Blues”

Sade, “Smooth Operator”

Geeshie Wiley and Elvie Thomas, “Last Kind Words Blues”

PJ Harvey, “Down by the Water”

Janet Jackson, “That’s the Way Love Goes”

Tina Turner, “Better Be Good to Me”

Salt-N-Pepa, “Push It”

Kate Bush, “Wuthering Heights”

Donna Summer, “I Feel Love”

Vashti Bunyan, “I’d Like to Walk Around in Your Mind”

Yeah Yeah Yeahs, “Maps”

Blondie, “Call Me”

Amy Winehouse, “You Know I’m No Good”

Sleater-Kinney, “Jumpers”

Lady Gaga, “Yoü and I”

Joanna Newsom, “Divers”

Bonnie Raitt, “I Can’t Make You Love Me”

Pat Benatar, “We Belong”

The Breeders, “Cannonball”

Cyndi Lauper, “Time After Time”

Erykah Badu, “Didn’t Cha Know”

Sinéad O’Connor, “Nothing Compares 2 U”

Karen Dalton, “Something on Your Mind”

Dolly Parton, “Jolene”

Aimee Mann, “Wise Up”

Brittany Howard, “Stay High”

Nico, “These Days”

Joan Baez, “Diamonds and Rust”

Chaka Khan, “Through the Fire”

The Pretenders, “Brass in Pocket”

Patti Smith, “Gloria”

Taylor Swift, “All Too Well”

Loretta Lynn, “The Pill”

Carole King, “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman”

Laura Nyro, “The Descent of Luna Rosé”

Stevie Nicks, “After the Glitter Fades”

Sharon Van Etten and Angel Olsen, “Like I Used To”

Valerie Simpson, “I Don’t Need No Help”

Billie Holiday, “God Bless the Child”

Big Mama Thornton, “Everything Gonna Be Alright”

Lucinda Williams, “Are You Alright?”

Shirley Collins, “Sweet Greens and Blues”

Beyoncé, “Love on Top”

Memphis Minnie, “When the Levee Breaks”

Dorothy Fields, “The Way You Look Tonight”

Ellie Greenwich, “River Deep—Mountain High”

Liz Phair, “Divorce Song”

Nina Simone, “Mississippi Goddam”

Abbey Lincoln, “Throw It Away”

Fiona Apple, “I Want You to Love Me”

Lauryn Hill, “Doo Wop (That Thing)”

Sylvia Moy, “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)”

Yoko Ono, “It’s Gonna Rain”

Rhiannon Giddens, “Julie”

Odetta, “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”

Alice Coltrane, “Blue Nile”

Britney Spears, “Toxic”

Cat Power, “He War”

Hole, “Violet”

Madonna, “Like a Virgin”

Althea & Donna, “Uptown Top Ranking” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com