The January 6 committee wrapped up what could be its final public hearing with a vote to subpoena Donald Trump himself for testimony Thursday.

But of more importance for the future was the hearing’s larger theme. The focus, vice chair Liz Cheney (R-WY) said, was “President Trump’s state of mind. His intent, his motivations, and how he spurred others to do his bidding.”

This is quite an important topic, because establishing Trump’s intent would be central to any eventual criminal case against him on this topic. And while the committee has made some real advances on this front, it isn’t yet clear what Justice Department investigators will make of their findings.

The subpoena to Trump, meanwhile, is unlikely to result in much at this late date. Trump will surely challenge it in court, which would take some time to resolve. If the GOP takes the House in the midterms, they could squelch the subpoena along with the rest of the committee’s ongoing work next year.

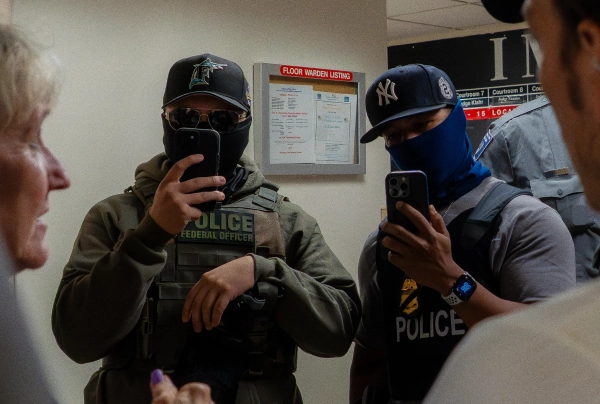

And even if Trump does testify he would likely just “take the Fifth” — invoking the Fifth Amendment’s protections against self-incrimination to avoid answering questions — like he recently did in New York state’s investigation into his business practices. (He probably won’t blow off the subpoena entirely, because he knows Steve Bannon got indicted and convicted for doing just that.)

The committee is still pursuing some investigative matters, but its focus will shift soon to writing a final report. And it isn’t clear how much new information that report will contain after so much was surfaced at these hearings. Thursday’s session contained some new factual information (including footage of Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, Mitch McConnell, and other congressional leaders working the phones to try to get help as rioters stormed the Capitol). But overall, it was more of a broad summary of the case against Trump so far, focusing on what exactly his intentions were.

Trump’s intent: Did he know he lost?

One question long hanging over this has been whether Trump “knew” he lost, or whether he actually believed his own conspiracy theories about Democrats stealing the election from him. Committee members made the case Thursday that he knew, citing, for instance, sudden orders he issued to quickly withdraw troops from Afghanistan, Syria, and elsewhere days after the election, to argue he knew he wouldn’t be in office much longer.

But there are problems with trying to prove that Trump “knew” he lost. For one, he repeatedly insisted, in private as well as public, that he did not lose. If he acted otherwise at some time, he can simply claim he changed his mind later. His troop withdrawal instructions could alternatively have been issued simply because he wasn’t sure how the election challenge would be resolved.

Moreover, Trump is not really the sort of person who embarks on a fair-minded factual inquiry of what is true or untrue and acts in accordance with that inquiry’s results. His M.O. is more in the realm of “what can I use?” or “what can I get away with?” rather than “what are the facts?”

What the committee’s evidence does clearly show is that, before and after the election, Trump badly wanted to stay in power, and went to extraordinary lengths to try to do so. Indeed, it seems the “true” results were irrelevant to him. He laid the groundwork for disputing the results well before the election, and he disputed the results regardless of what his campaign advisers told him about the outcome’s legitimacy, or what his Justice Department told him about the lack of evidence for voter fraud.

Trump’s intent: What did he hope would happen at the Capitol?

Of even more importance is the question of what, exactly, Trump intended to happen on January 6.

When Congress impeached Trump for his actions here, the charge was “incitement of insurrection.” Much discussion at the time focused on the question of whether Trump really did envision a violent mob storming the Capitol. In his speech, he told his supporters to march “over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard.” And while he had urged them to “fight like hell,” his lawyers claimed that was merely a common political metaphor.

The committee made a hugely important contribution to the factual record on this back in June, when it revealed testimony and evidence that Trump very much intended to go with his rally attendees to the Capitol that day, was prevented from doing so by the Secret Service, and became furious because he was stopped. The situation would have gotten an order of magnitude crazier if that had happened.

“We all knew what that implicated and what that meant,” a White House security official, whose identity was kept anonymous, testified. “That this was no longer a rally, that this was going to move to something else if he physically walked to the Capitol. I don’t know if you want to use the word insurrection, coup, whatever. We all knew that this would move from a normal democratic public event into something else.”

Former White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson also testified that Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani knew about the plan to head to the Capitol four days in advance and claimed to her that chief of staff Mark Meadows “knows about it,” and that Meadows subsequently told her “things might get real, real bad on January 6.” One rally organizer also wrote in an email two days prior that Trump planned to call for a march to the Capitol “unexpectedly,” but that this had to be kept secret. Then, on the day itself, Trump complained that some rally attendees with weapons should be allowed past security because “they’re not here to hurt me,” per Hutchinson.

So: What did Trump hope would happen when he led his crowd of supporters, some of whom he hoped would be armed, to the Capitol while Congress counted the electoral votes? At best, it seems, he hoped to intimidate them into handing the election to him. At worst, it was something darker.

But we are still lacking direct testimony from someone really in a position to know — like Meadows (who has cited executive privilege and is embroiled in a court battle with the January 6 committee over his testimony), or perhaps other Trump advisers or allies who pleaded the Fifth.

“There were a whole number of places in our investigation, where various witnesses refused to say anything, invoking the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination, meaning that they think they might be exposing themselves to criminal prosecution precisely in dealing with President Trump,” Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) told reporters after Thursday’s hearings. “So we would like him to come forward and explain what was happening at those various points.”

Yet Trump likely won’t be so forthcoming — subpoena or no subpoena.

Ben Jacobs contributed reporting.

Our goal this month

Now is not the time for paywalls. Now is the time to point out what’s hidden in plain sight (for instance, the hundreds of election deniers on ballots across the country), clearly explain the answers to voters’ questions, and give people the tools they need to be active participants in America’s democracy. Reader gifts help keep our well-sourced, research-driven explanatory journalism free for everyone. By the end of September, we’re aiming to add 5,000 new financial contributors to our community of Vox supporters. Will you help us reach our goal by making a gift today?

Sourse: vox.com