“Train: the final journey of RFK” is a witty, oddly enough

way, affecting the exhibition, which opened last month in San Francisco

The Museum of modern art. Although the train in question is one that

almost fifty years ago, was carrying the body of Robert Kennedy from new York

in Washington, D.C. for burial at Arlington cemetery, not

about Kennedy. A show about death—or, more precisely, on

the relationship between photography and death.

Their relationship had always been close. Photos Bart

wrote in “camera Lucida”, “it’s kind of primitive theatre, a kind of tableau vivant,

the image of the motionless and made-up face

under which we see the dead.” Movement is life, and the film is about

movement: for the study of movement this technology was invented movie. But

photos immobilizes. Pictures to pull a person out of time. And we

to take a picture. We present one day, looking at them, when

the people in them are no longer alive. Even when you look in the photo

some random person, anyone, a few years ago, somewhere in your mind

the thought creeps in: “and this man, probably already dead.”

“Untitled” from the series “RFK funeral train”, 1968.

Photograph Paul Fusco / Magnum / courtesy Danziger Gallery

Robert Kennedy is dead. He was shot in the head at 12:15 am,

June 5 1968 in the kitchen of the Ambassador hotel in Los Angeles,

moments after declaring victory in the California Democratic primary. It

was campaigning for President, not even three months. He never

regaining consciousness, died the next day. His body was flown back to

New York, June 8, the funeral took place at St. Patrick’s

Cathedral. Immediately after this, the coffin was set by train

Washington.

The heart of the Museum show is a collection of twenty-one pictures

on Board the train with a photographer named Paul Fusco. It was

last-minute job to see where Fusco was the staff

photographer, and he suggested that his main task will be in Arlington,

where Kennedy was to be buried next to his brother John. But when

the train emerged from the Hudson river tunnel, Fusco was amazed to see

the people lining the tracks. He found a spot by the open window, and, for

at eight o’clock he took the train to get to Washington, he took a picture of

after pictures of the crowd that came to witness the body of Kennedy

carried to his grave.

“Untitled” from the series “RFK funeral train”, 1968.

Photograph Paul Fusco / Magnum / courtesy Danziger Gallery

“Untitled” from the series “RFK funeral train”, 1968.

Photograph Paul Fusco / Magnum / courtesy Danziger Gallery

These pictures eventually became best known works

photojournalism from what was the Golden age, the era of big

mass circulation picture magazines: life, Look, Saturday

Evening post, Paris match, and stern. Fusco carried three cameras

with him on the train: dual cameras Leica rangefinder and Nikon S. L. R.

Almost all the shots, he used Kodachrome film, and he went

thousands of pictures. By the end of the journey, as dusk fell, his

the exposure time to one second.

Trains in the northeast corridor does not pass through the superior

neighborhoods. People who spontaneously turned out to see

funeral train pass by Kennedy biographer Evan Thomas says there was

million was, in appearance, mostly working class, and there were white

and African-Americans often standing in a cluster together. In 2018

looking back on these images as the train approaches the terminal and

the light begins to fade, you realize that you are watching the finals

watch great Democratic coalition that dominated American

policy after the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932—a coalition of

what will collapse in six months after the election of Richard Nixon,

and who is now dead, like Robert Kennedy.

“Untitled” from the series “RFK funeral train”, 1968.

Photograph Paul Fusco / Magnum / courtesy Danziger Gallery

Photos of Fusco amazing in all respects. Technically,

on Kodachrome film produces very rich images. It was a hot day,

but it was June, and the light—Fusco seems to have been shooting people

on the West side of the track that should be a problem, as

for the sun in the sky is almost tangible, weighty presence.

As for the faces, it was the emotion that brought people to

standing, waiting, sometimes for hours, beside the tracks in the heat and

these emotions are easy to read. Fusco must have realized that this person

what he wanted, and he compensated for the movement of trains

focusing on one person and moving the camera, when he pressed

shutter, so that individuals often fall into the focus on

the slightly blurred background. There is nudity in them, which is rare

in the state—these people don’t think that someone is watching them—

nudity that many photographers have tried to capture. Here it is.

“Untitled” from the series “RFK funeral train”, 1968.

Photograph Paul Fusco / Magnum / courtesy Danziger Gallery

“Untitled” from the series “RFK funeral train”, 1968.

Photograph Paul Fusco / Magnum / courtesy Danziger Gallery

All but two photos Fusco remained unpublished for thirty

years. This appears to be a consequence of the fact that the opinion was

biweekly publication and its main competitor, life was a weekly, so

next issue came out, the funeral of Kennedy

was covered already in another place. View printed two Fusco

pictures in black and white.

The pictures remained virtually unknown until 1998, the thirtieth

anniversary of the assassination, when the selection was published in

George, political and life style monthly he founded and edited

John Kennedy, Jr., Robert’s nephew (who would die in the crash

the plane he was piloting, a year). Some of the images were published

in a small-press book in 1999, and then, in 2008, on the fortieth

anniversary, they were published by aperture, and this release brought

them to the attention of other photographers and artists.

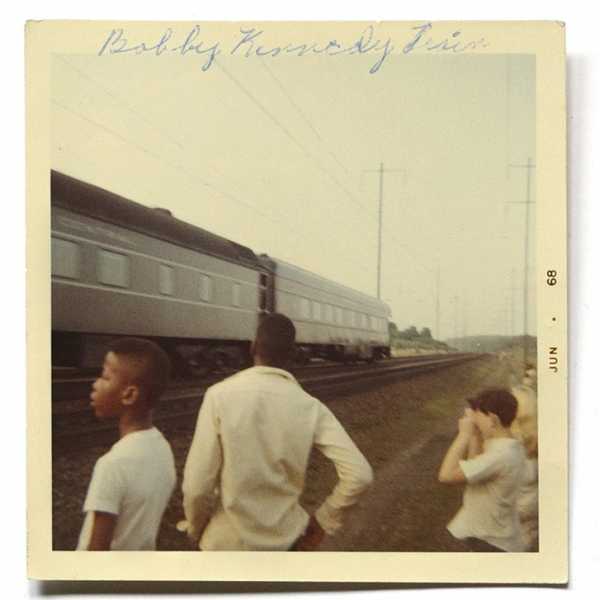

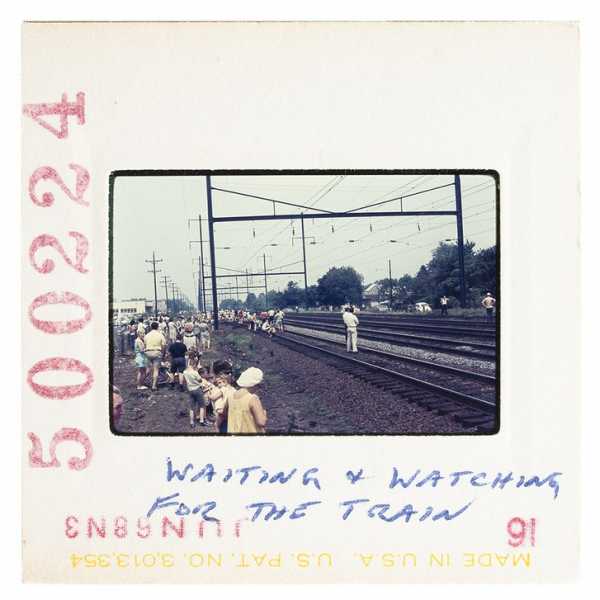

“Elkton, Maryland” 1968; from rein Jelle Terpstra “kind of people” (2014-18).

Photo Annie Ingram / courtesy of Melinda Watson

“Tullytown, Pennsylvania,” 1968; from rein Jelle Terpstra on “popular opinion.”

Photos of William F. Wisnom, senior / CourtesyLeslie Dawson

What’s smart Museum show, curated by clément

Chéroux and Linde Lehtinen, is that it complements the photos Fusco with two riffs on them.

The first Dutch artist rein Jelle Terpstra, who was inspired by

to the 2008 Edition of the diaphragm and realized that a lot of people

Fusco removed from the train behaved for the cameras. They

photographed too. Terpstra spent four years hunting down a lot

these Amateur photos and collecting their photos, slides,

and home movies.

Image technically completely different from the prints Fusco. In

colors on the images are not faded, and images on slides

tiny. The work is almost conceptual: the adventure of recovery

photos, not the photos themselves that make artistic experience.

The most vivid pictures of super 8 films (digital show) from

the great black train, a little intimidating reminder of what it is

state funeral we are watching.

“June 8, 1968,” 2009.

Photo Philippe Parreno / courtesy of Maya Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation

Another riff was made in 2009 by French artist Philippe Parreno:

the reconstruction of the train. Parreno have hired people to dress in

period clothes and stand by the side of the track, and then

shot them from a passing train. The film he produced about seven

minutes.

It should never have worked, but it’s not. For technical reasons, Parreno

finished shooting a big movie in California, and the landscape

obviously the West coast. The wrong side is the trace of the aura of the crowd in

the original pictures, despite the costumes, no. But, shooting

70-mm. film, Parreno captured light effects that make Fusco

the images are so lush.

“June 8, 1968,” 2009.

Photo Philippe Parreno / courtesy of Maya Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation

Parreno realized that Fusco was trying to do with the person and

he managed, brilliantly, to embed photographic images

in fact still lives in the cinematic world. He did it

having his “actors” to remain perfectly still, so they seem to be frozen in

time as the train rumbles along and the trees blow in the wind. They

as a phenomenon. It’s as if, fifty years later, Kennedy

the witnesses came back, as they once were. When the train passed,

they disappear again. And so, very soon, we will. And

terrible finale special show!

“June 8, 1968,” 2009.

Photo Philippe Parreno / courtesy of Maya Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation

“June 8, 1968,” 2009.

Photo Philippe Parreno / courtesy of Maya Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation

Sourse: newyorker.com