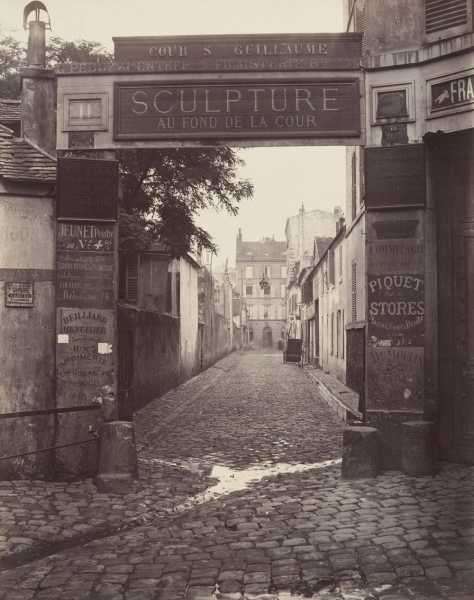

1 / 10ChevronChevronPlace Saint-André-des-Arts. c. 1865. © Charles Marville Marville/Musée Carnavalet/Roger-Viollet/The Image Works.

The Paris we know is shaded white and gray, a city of zinc roofs and pale stone façades fitted with iron balconies and crosshatched with whitewashed shutters. Its parks are laced with gravel paths that leave your shoes coated in a fine chalky film. In the blue hour of middle evening, just after the sun has set but before the light has finished draining from the streets, the roofs glow blue, sometimes so intensely that the blank walls below pick up the color and reflect it, giving the city a submerged quality, as if it had sunk quietly to the ocean floor.

Aside from that phosphorescent flush, the work of a few intrepid graffitists, and the ghoulish green light projected by the electric crosses marking the entrances to pharmacies, most buildings are blank, the color of a wishbone picked dry and left out to bleach. Paris is serious about keeping its dignity austere. A law passed in the eighteen-eighties prevents anyone from posting anything on any building in the city under any circumstances. That’s why the startling thing about a photograph of the Place Saint-Andre des Arts, taken around 1865, isn’t the two covered wagons resting on wooden wheels in front of the building, or the horses hitched to them, but the building itself, which is covered in words: ads for carpenters, for leather, for wine, for a steam bath on Rue Monsieur le Prince and a humbler “water bath” on Rue Larrey. “MECHANICAL BEDS AND ARMCHAIRS FOR THE ILL AND WOUNDED,” reads the text above a fresco of a patient propped up with the help of one of the fabulous machines.

The picture was taken by Charles Marville, a photographer hired by Paris’s historic-works department in the late eighteen-fifties to capture before-and-after shots of the city as it was razed and rebuilt during the Second Empire. The first Bonaparte had chosen to remake all of Europe. His nephew, Louis-Napoleon—who returned from years of exile to become President of the Second Republic briefly before being crowned emperor, as Napoleon III—began by setting his sights on a single city. To mastermind his project, he chose Georges-Eugène Haussmann, a career bureaucrat and an early ally, giving him free reign to demolish, align, remodel, expand, and evict on a scale that still seems close to insane. A project of this magnitude needed documenting, not least for propaganda purposes. The camera, barely two decades old, was the obvious tool.

As the exhibition of his photographs at the Metropolitan Museum makes clear, Marville was the right man for the job. For starters, he was a local. His father was a tailor, his mother a laundress. He grew up on a cramped street near the Louvre that later vanished to make way for one of Haussmann’s imperial avenues. Like Baudelaire, his contemporary, Marville honed his eye on Paris; the city taught him to see. He knew its places and its people, but he had ambitions beyond the practical realm of his upbringing. If he had reservations about scrapping the last name he was born with, Bossu—the word means “hunchback”—he was cured of them by Victor Hugo, who published his novel about the bossu of Notre Dame in 1831, around the time that Marville chose his alias. He was eighteen, an art student at the Academie Suisse, and apparently not bothered by the idea of making a clean break with his family’s history. Marville understood tradition without getting too sentimental about it. You can hear some of the romantic eagerness of a self-made man in his chosen name, which sounds like a mashup of ma ville and merveille: Marville, my marvellous city.

It’s hard to fathom just how enormous an undertaking the remaking of Paris was. In the early eighteen-thirties, seven hundred and eighty-five thousand people lived there. By 1851, the year that Louis-Napoleon staged his coup, there were more than a million. (New York had half as many.) That number only grew as workers started flocking to the city once construction was under way. Paris had long been in bad shape, much of it a medieval warren of “cold, dirt, sickness, ignorance, and want,” as Dickens put it in “A Tale of Two Cities.” Napoleon III didn’t come up with the idea of renovating the city; important projects had begun in the eighteen-thirties and forties. But he and Haussmann changed the scale of the operation by many orders of magnitude. Crumbling houses were extracted like so many rotting teeth, and replaced with Haussmann’s signature apartment buildings, with their tall windows to let in fresh air and sunshine. Narrow, filthy streets were razed to make way for wide boulevards—the better for the swelling bourgeois class to stroll along on a warm spring day, and for the military to roll its cannons down should an uprising need to be quashed.

Some of Marville’s photos capture the profoundly surreal quality of the transformation. Here is Boulevard Henri IV, at the eastern edge of the Marais, looking like a location for “There Will Be Blood”: just dirt and rubble under a flat sky, plus a couple of horses loitering in front of a lonely building that wouldn’t seem out of place in an abandoned frontier town. In the distance, at the Place de la Bastille, the tapered July Column could be a derrick gushing oil. The image is just as weird as anything Dali ever made. Here are the Carrières d’Amérique, the quarries in the newly incorporated Nineteenth Arrondissement, which were exploited, for their gypsum and millstone, to make new buildings in the city center. Broken-off railroad ties litter the ground in front of yawning ditches. It’s a desolate, scorched-earth kind of place. Today, the Buttes-Chaumont Park, one of the greenest spots in Paris, is there. Here are the barracks of the Fifth Arrondissement’s calf market, with its heavy wooden beams and stone pillars, abandoned because the emperor has decided, reasonably enough, that livestock shouldn’t hang out in the center of the city anymore. And here is Napoleon III’s pet project, the brand-new building of Les Halles market, light streaming through its glass roof. It’s exactly the structure the emperor had in mind when he demanded that his architects make him “umbrellas of iron”: modernity incarnate.

For the viewer accustomed to Paris’s relentless beauty, it’s easy to be fooled by what seems familiar in Marville’s pictures. Many of them capture a certain sheen on the cobblestones, like the one in the Ned Rorem song “Early in the Morning,” about a woman eating croissants at a cafe on Rue François-Premier (a Haussmannian street if ever there was one) while she waits for her lover to show up: “They were hosing the hot pavement / With a dash of flashing spray / And a smell of summer showers / When the dust is drenched away.”

The glisten caught by Marville’s camera is no flashing spray, however, but raw sewage, left festering on the cobblestones to splash up under carriage wheels and seep into the soft soles of shoes and the hemlines of dresses. Marville’s Paris was more Middle Ages than New Wave, and you can bet it didn’t smell like summer showers. In “Tableau de Paris,” his rollicking, pungent chronicle of the city in the late eighteenth century, the writer Louis-Sébastien Mercier describes the “cadaverous odor” emanating from churches full of decomposing bodies awaiting proper burial, and the putrid fosses d’aisances, indoor pits where a household’s excrement was collected. The air reeks constantly of shit, Mercier tells us. The pits are badly made, not to mention terribly maintained, and their contents run into neighboring wells used by bakers turning out their daily loaves: “Oh superb city! What foul horrors are hidden in your walls!” After cadavers stolen or bought by young surgeons eager for anatomy practice are hacked up, the discarded parts often wind up in the fosses—a dash of literal spleen to season Baudelaire’s metaphor.

For relief, turn to Marville’s photos of public pissoirs, one of Haussmann’s more ingenious projects for cleaning up the streets. Seen through Marville’s lens, they become sculptural, even elegant, objects, equal parts form and function. The stalls are organized in a row or an artful ring, and blocked off from prying eyes by a metal fence that shields a body from knees to neck. Each is topped with an ornate street lamp, markers of Paris’s emerging status as the City of Light. “Step right up,” the lamps say. “No shame in availing yourself of a functional sewage system. This is what progress is all about.”

Napoleon III liked to play up the humane goals of his grands travaux. In an 1850 speech, he announced that his government would “open up popular quarters which lack air and light, so that sunlight may penetrate everywhere among the walls of the city just as the light of truth illuminates our hearts.” There was truth behind the treacle. Disease was flushed out, dark alleys were illuminated, running water was installed, public parks were built, transportation was improved. But, as David Harvey points out in his excellent study “Paris, Capital of Modernity,” the notion that the remaking of Paris was a project that only Napoleon III’s prophetic vision and Haussmann’s skill could have achieved was also convenient hype, “a founding myth [that] helped secure the idea that there was no alternative to the benevolent authoritarianism of Empire.” Haussmann, Harvey writes, was prepared “to ride roughshod over the opinions of others and make absolutely no concessions to democracy.” The reconstruction of Paris, with its insistence on order, scientific planning, and the unstoppable march of progress, was, in many ways, a project directly inherited from the Enlightenment. It was also a pitch for the benefits of despotism.

Haussmann relied on what he called percements: wide avenues that would pierce through the clotted chaos of the city, clearing out everyone and everything in their way. It’s a violent word. Paris, for Haussmann, was a boil to be lanced. (In his memoirs, Haussmann unsurprisingly served the idea with a benign spin: “It is easier to cut through the center of the pie than through the crust.”) Thousands of people were displaced as the city’s new byways sliced straight through the places they had lived for generations. Who were they? What did they think and feel about the convulsions that their city was made to undergo?

In Marville’s first years working for the city, his shutter moved too slowly to capture people as more than faint smudges, ghostly blurs haunting the edge of the frame. Even after shutter speed had been shaved down to seconds, he liked to take pictures in the early morning, when he had the streets to himself. His photographs have some of the idyllic emptiness of the drawings made a century earlier by the Grand Tourists visiting Rome, as if teeming Paris were in the same state of picturesque abandonment.

To get a sense of the people Marville avoided, better to look to Daumier, Marville’s exact contemporary and just as much a documentarian with his sketchpad as Marville was with his camera. People were Daumier’s raison d’être, and he captured so many splinters of life, as it was disrupted by Haussmann, that the composite portrait is as gloriously messy as Marville’s photos are poised and still. In one drawing, from the early eighteen-fifties, a family stands on a strange street, fresh from being relocated after the “expropriation” of their home. Carriages rumble by. Madame, in her cape and bonnet, and Monsieur, in his top hat, pitifully clutching the family birdcage, stare, open-mouthed and saucer-eyed, at the new neighborhood they’re supposed to call home. Their little son, absorbed by some worm or rock on the ground, has already adjusted to the change of scene, as children do. The bewilderment of the parents is extreme—one more second of gaping and they’ll be run over by a horse and cart—but so is the elation of the wizened couple in a second Daumier sketch, standing in nightcaps at their open window and grinning like they’ve just won the lottery. In a sense, they have. To their left, workers are taking pickaxes to a neighboring building. The sickly plant on their sill is suddenly blasted with sun. For the first time in their lives, they can see the city below.

“Old Paris is no more (the form of a city / Changes more quickly, alas! than the human heart),” Baudelaire wrote. Marville kept his cards closer to his chest. His job was to record his city’s rebirth, not to lament its passing, though that distinction isn’t always so clear. The most unsettling photograph in the Met exhibit is from 1876, showing the ongoing construction at the Avenue de l’Opéra. By the time it was taken, Napoleon III had died in exile, and Haussmann had fallen out of favor, accused of spending exorbitant amounts on civic projects. (Haussmann, with his potato-shaped head and unfortunate neckbeard wrapped like a bandage around his jaw, was an easy mark for Daumier; in one caricature, he is given a beaver’s body from the neck down, looking like one of Maurice Sendak’s wild things grown to paunchy middle age as he hulks over an apartment building, fussily clutching a trowel.) Prussia had gone to war with France and won. The revolutionary Commune had briefly introduced socialist rule to Paris before being violently suppressed.

Still, the reshaping went on. The Opéra and its surrounding neighborhood were the jewel in Haussmann’s crown, a prime showcase for the upscale conformity he prized, and for once Marville focusses his camera on a group of people, two dozen or more, gathered at the site. They stand in a line on what, until recently, was the working-class neighborhood of Butte Saint-Roch and is now a pile of rock and dust. Others perch like buzzards on top of the surrounding decrepit buildings marked for destruction, peering out over the immediate void. If they squint, they might just be able to see the delicate trees that line the completed boulevard in the foreground and the little dog that sniffs at the new sidewalk, signs of the kinds of people who will soon move in to take their place. It’s a knotted, ambivalent image. We have reached the end of the play, and the chorus has come out, at last, to tell us what we are supposed to remember, what moral we should have perceived. What kind of song are they singing? Something happy, or furious, or wistful, or none of the above? There’s no way to tell. We have to be content with knowing that they were there.

Sourse: newyorker.com