In 1996, neoconservative writers Bill Kristol and Robert Kagan published a highly influential article in Foreign Affairs entitled, “Toward a Neo-Reaganite Foreign Policy.”

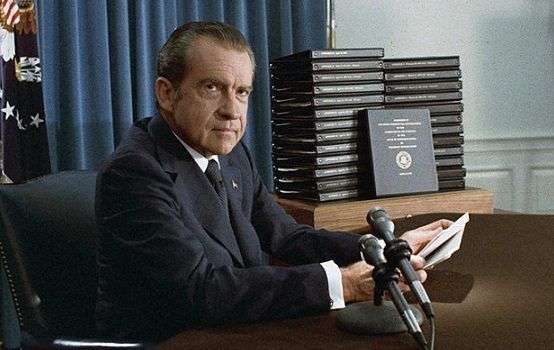

Many believe the piece laid the intellectual foundations for much of the post-9/11 George W. Bush-era foreign policy. Today, however, we need to reject the neoconservative musings of Kristol and Kagan and return to a mode of thinking that is realistic in the classical, even Machiavellian sense. The best recent American practitioner of this type of policy was Richard M. Nixon, which is why it’s time for a neo-Nixonian foreign policy.

Ironically, to move in this direction will mean closing the door on Nixon’s greatest diplomatic achievement—the opening to China.

As the trade war between the U.S. and China escalates and both nations begin targeting each other’s high-tech champions, we are seeing the end of a world order. The so-called era of “Chimerica,” as coined by historian Niall Ferguson—who, ironically, is the official biographer of Nixon’s right-hand man Henry Kissinger—is coming to an end. This era began thanks to the efforts of President Nixon and Kissinger. Yet its very death actually opens a new door—towards the type of essential, realist foreign policy that would have been eminently understandable to Nixon himself.

Advertisement

The famous opening to China, initially orchestrated in almost exclusive secrecy by Nixon and Kissinger, was brilliant in conception and, for the most part, in execution. However, it was also a strategy based upon a set of contingent geopolitical realities that radically changed after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union.

Of course, by that time, Sino-American relations had entered a new phase. No longer were geopolitical competition and grand strategy—key concerns for Nixon and Kissinger—the primary elements of America’s China policy. Economics and business relations became the new focus. A market of over one billion people beckoned, as did less expensive labor costs.

However, prescient as usual, President Nixon at the end of his life postulated that his own signature policy initiative might have given birth to a “Frankenstein.” Since then, Western assumptions that China would become “Westernized” and a “responsible stakeholder” in the largely American geopolitical order have proven wrong.

Nixon recognized the potential consequences, both domestic and international, of a China that was not following the path that had been assigned to it by various Western policy elites. He is unlikely to have continued embracing a policy that was empowering America’s next great geopolitical competitor.

Chinese president Xi Jinping has been remarkably candid about his country’s desire to become the new major power on the world stage. Between its ambitious “Belt and Road” initiative designed to economically bring together Eurasia and its large military investments meant to keep America out of its near abroad, China has proven itself a worthy competitor to the U.S. It has a strong vision of a new world order in which it reclaims its long-standing historical position as the “Middle Kingdom.”

While many business groups and those with ties to China may still want to pretend that America can go back to the halcyon days of the 1990s or the early 2000s after China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, the Trump administration’s frontal assault on Chinese duplicity and threatening behavior shows this is unlikely.

President Trump is far from as subtle a politician as Nixon. However, he is laying the foundations for a neo-Nixonian foreign policy for the future, one that will help secure America’s position in global affairs while preventing the ascendancy of China from overturning the entire global order and installing a sort of modern-day tianxia.

It is critical for aspiring policymakers to corral the correct Trumpian instincts into a more comprehensive, coherent, and sustainable grand strategy that will outlive the Trump presidency.

To do this, they should create an “Iron Quadrilateral” of four interlocking sub-strategies, which together would form a grand strategy aimed at preventing a hegemonic power, or concert of powers, from dominating Eurasia.

The “Reverse Nixon to China”

First and foremost, China and Russia should not ally. This would be a geopolitical disaster for the U.S., which is why it has been a cornerstone for much of Cold War policy since the Nixon era.

The largest country in the world by landmass, and also possessing a large number of nuclear arsenal, Russia working in concert with the second-largest (and soon to be largest) economic power in the world to isolate the U.S. is exactly the scenario that famed geopolitician Sir Halford Mackinder indicated is essential to avoid.

This calls for recasting the American relationship with Russia at a fundamental level. Specifically, Russia should be split from China in a way not dissimilar from how President Nixon and Henry Kissinger worked to exploit the Sino-Soviet split to counterbalance the Soviets.

At that time, China was clearly the weaker power in the triangular diplomatic gambit. Today, it is Russia.

NATO should informally recognize that Russia would have what amounts to a sphere of influence. There will be a red line, but the red line will not be set in any former Soviet republic. Ukraine and Georgia will never be admitted into NATO and must remain essentially neutral entities between the West and Russia.

If Russia’s western frontiers can be managed, the U.S. should actively encourage Moscow to shift its focus towards Central Asia.

Russia will never be an ally of the United States in the same way Japan, Australia, or the European powers have been. But this is not needed in order to achieve the first imperative of the “Iron Quadrilateral.” Russia simply need not be a permanent spoiler that is willing to tilt permanently against the U.S. and in favor of China.

Embrace Richelieu in the Middle East

The Middle East still matters to American interests, but less so than in the past and for different reasons.

With America’s shale miracle still changing the international energy landscape, stability in the region matters less from an energy security standpoint. Further, China gets far more of its energy from the Middle East now than the United States does. A destabilized region will make Chinese growth that much harder. Meanwhile, a shifting of military personnel from the Middle East will be required in order to bolster America’s presence in the Indian Ocean and the South and East Asian Seas.

To that end, this author has previously argued for a policy of “divide and conquer” akin to that devised by Cardinal Richelieu—a policy that would secure minimal U.S. national interests under the present situation reminiscent to Europe’s own Thirty Years’ War.

Unlike most administrations since the end of World War II, the current one should finally stop offering a blank check to Saudi Arabia. However, unlike under Barack Obama, who sought to tilt to Iran, the Trump administration should suffer no illusions nor expend much energy working to bring Tehran into some sort of regional security architecture. As happened with the old European Habsburgs, France, Sweden, and other powers in the Thirty Years’ War, a long-term war of exhaustion will eventually lead to a balance of power on its own.

Strengthen Japan

Japan is a critical element of the “Iron Quadrilateral.” Under no circumstances can it be hung out to dry. Nor can it be merely assumed that the Japanese can then take care of themselves if the U.S. pulls out of its long-term relations. This is an area where Trump, or his successor, needs to consider our alliance structure in East Asia with greater care.

Japan, along with India and Russia, will form part of a critical potential counterbalance to China over the next few decades. The U.S. should consummate the “Asian Pivot,” started under Obama but under-resourced. It should also shift the lion’s share of our defense investment in Europe towards East Asia. In a nutshell, if Trump wants savings from reducing our overseas posture, it should come from NATO and Europe, not East Asia.

Fully Embrace India

President Trump, or his successor, should not view the U.S.-Indian relationship primarily through the lens of trade. While India will certainly seek to retain its options and geopolitical independence, the U.S. should do nothing to undermine what should be a budding friendship. Even at the risk of allowing India greater latitude on trade than most other nations, America should continue to try to develop economic relations while also seeking to facilitate India’s military cooperation with other Asian-based powers. This would include not just Japan, but Australia as well. In essence, the U.S. should cultivate the so-called “Quad.”

Without a dramatic change from the status quo of foreign policymaking in Washington, America’s strategic position will further decay and facilitate the rise of a Sino-centric world order inimical to U.S. interests and values. But by referring back to one of our greatest strategists, America can create a long-term policy that effectively confronts what is likely to be the greatest geopolitical challenge this country has ever faced.

Greg R. Lawson is a contributing analyst with the global, web-based geopolitical consultancy Wikistrat. His work on foreign policy has been published in The Hill and The National Interest. Mr. Lawson has also been a longtime government affairs professional and grassroots organizer in Ohio.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com