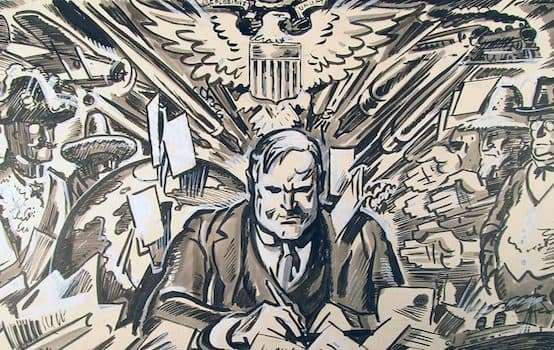

Any analysis of the presidency of Herbert Hoover, of course, overwhelmed by his failures in the struggle against the great depression. And it’s true that Hoover’s policies might have turned ordinary cyclical downturn into the worst economic disaster in American history. However, when assessed against the restrained national security policy of the Constitution the compilers and more than a century of expertise, Hoover is security policy has been better than any President in the 20th century, remains unsurpassed so far in the 21st, and stands as one of the best in American history.

Hoover dramatically improved relations with Latin America. He also kept U.S. from war in Asia and was successful in achieving disarmament among the major Maritime powers. He shrewdly believed that military intervention abroad is usually caused more problems than it solves, including the loss of freedom at home. He also believed in closely adhere to the original creators of the anti-militarist and anti-NATO orientation, and did not require to expand the President’s role in foreign policy for his limited role envisioned by the Constitution.

In practice, foreign policy Hoover demanded that foreign peoples and Nations to fight their own battles. During his four-year term, he passed up more chances for American intervention abroad than any other similar full-time President of the 20th century. As a result, during the term, not the Americans killed in foreign conflicts.

In Latin America, Hoover gave this area the highest priority in U.S. relations abroad. His peaceful policy, largely continued Franklin Roosevelt, will pay big dividends prior to and during World war II, when Roosevelt tried to enlist support against a possible Nazi infiltration in America.

Within 30 years after the Spanish-American war, the United States controlled and actively patrolled Latin American countries, including the internal Affairs of these countries. Allegedly for security in the Caribbean, in particular, that the Panama canal, the US intervened militarily in Panama, Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic. Before the first world war, Woodrow Wilson was launched two incursions into Mexico. The reason for these violations was to support the business interests of the United States in the enforcement of contracts and debt collection-called “dollar diplomacy.”

Hoover aimed to change that interventionist policy. Although FDR is usually credited with initiating a “good neighbor” policy in the region that United America against the axis powers, it was the cleaner, who promised that the US stop interfering in the internal Affairs of Latin American countries, even the Coolidge administration refused to promise. Hoover military stayed, even when Latin American countries fell on the numerous depression induced by revolutions, which do not fulfill their American loans, and confiscation of American assets through nationalization.

He also withdrew U.S. Marines from Nicaragua, ending a two-decade military presence in that country, and he would do the same for Haiti, but for the legislature of Haiti refuses to Approve the terms of the Treaty ending the occupation. (Hoover had made plans that allowed FDR to initiate removal of the Executive agreement in 1934). At the same time, U.S. relations with Haiti have improved significantly, as the cleaner is allowed Haitians take over most social functions, the military situation over, and refrained from interfering in Congressional elections Haiti.

In Japan: when Japan invaded Manchuria in September 1931, Hoover historian Alexander DeConde has noted that “the fighting does not threaten American security or other material threats to American interests.” Hoover shrewdly noticed at the time that “these [Japanese] acts do not endanger the freedom of the American people, the economic or moral future of our nation. I’m not suggesting not to sacrifice American life for anything short of that.”

Although Japanese and Russian investment in Manchuria was significant, British and American investment was not. Hoover also came to the conclusion that war with Japan is not only sea, but also will attract the American troops in China arming and training Chinese. Instead, he chose to lead mediation efforts to try to resolve the crisis.

Hoover’s policy towards Japan should be analyzed through the prism of the First World war, which was a meat grinder for the powers involved that they were inclined to push back against the Japanese. This means that not only the instincts of a vacuum cleaner is good, but his hands were tied: he could not go to war, even if he’d wanted to. In fact, with a war-weary American public elected a Quaker hoover in the first place because they were away to a distant war, which has already sucked the life and national resources.

In addition, given the poor state of its fleet, it is unlikely that the United States could win the war with Japan in 1931. George C. herring concludes:

It was conventional wisdom in the 1940s-years that the firm Western response in 1931 would have prevented the Second World war. The so-called Manchurian/Munich analogy, which preached the need for resistance to aggression in the beginning, became the stock-in-trade of postwar US foreign policy…but there is no certainty that the stronger response in Manchuria would have prevented the subsequent Japanese and German aggression. No non-response needs to ensure a future war. Neither Japan nor Nazi Germany at that time was a master plan or clear timetable for the growth. Conventional hard truth is that the Western powers in 1931 lacked the will and means to stop Japan’s conquest of Manchuria. …Went to war in 1931 could be more catastrophic than a decade later.

The signing of the London naval Treaty of 1930: in President Warren Harding’s initiative, the Washington conference of 1920-1921 resulted in the first arms limitation agreement between the great Maritime powers. The Treaty, however, is limited only battleships and aircraft carriers, no cruisers, destroyers and submarines. However, in the London naval Treaty of 1930, the largest Maritime powers agreed to reduce all categories of naval ships until 1936. The agreement was the first comprehensive naval arms limitation Treaty in recent history that covers all the ships.

Given that nuclear weapons, Intercontinental-range and long-range bombers are now allowed for the defense of the United States without foreign alliances, bases and military adventures may return to Hoover, and the founders more realistic and affordable foreign policy is in order. And given the nearly $21 trillion national debt, national exhaustion for the last intervention in the middle East, five simultaneous drone wars that the US currently holds, and, as a consequence of the election of a populist President who promised a less tight U.S. foreign policy, now would be a great time to follow Hoover’s example. Back to the future by re-enacting the Hoover-style “independent internationalism” is the only way to ensure that the United States will retain its status as a great power for a long time.

Ivan Eland – senior fellow and Director of the Center for peace and liberty at the independent Institute, and author of the new book eleven presidents: promises and results in achieving limited government. His forthcoming book war and the presidency: the rescue of the Republic from failure in Congress.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com