Why we can’t look away from before-and-after pictures

From Jenna Jameson’s keto diet progress to the #10YearChallenge, people love transformation pictures. But do they do more harm than good?

By

Cheryl Wischhover@CherylAnneNY

Feb 20, 2019, 7:30am EST

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

Why we can’t look away from before-and-after pictures

tweet

share

Former porn actress Jenna Jameson is a mainstay on sites like People, US Weekly, and the Daily Mail. Given her history in what some may consider a salacious industry, coverage in tabloids probably doesn’t sound surprising. But Jameson also shows up almost weekly on outlets like Women’s Health. In fact, the fitness and wellness site has posted around 50 stories about her since July 2018.

“The main reason she’s resonating is that she continually posts such impactful before-and-after photos of her weight loss journey,” says Amanda Woerner, the executive editor of WomensHealthMag.com.

See for yourself:

Jameson, 44, has transformed herself into the face — and body — of the controversial keto diet. She’s lost more than 80 pounds since giving birth to her now-toddler daughter Batel. On Instagram, where her followers number over 400,000, she’s documented it all, complete with Trader Joe’s food recommendations and keto-friendly recipes for “savage cabbage.” In the beginning of December, she even started a separate Instagram page dedicated to the keto diet, which now has more than 47,000 followers and features primarily recipes, motivational memes, and regrammed keto information. But it’s the truly eye-popping transformational photos that are getting Jameson press coverage and ultimately growing her following.

Humans can’t resist a transformation story, and social media has provided a perfect home for regular people to document their own weight loss and other kinds of shape-shifting, including the recent “10-Year Challenge” and plastic surgery changes. Even non-human “improvements,” like recovered formerly sickly rescue dogs and Mandy Moore’s breathlessly documented kitchen renovation, are ravenously consumed. A search of the #BeforeAndAfter hashtag on Instagram spits back more than 12 million results, ranging from weight loss to hair color changes. (The more niche #KitchenReno hashtag yields more than 128,000 posts.)

Sure, Jameson’s ascendancy as “keto queen” represents an intersection of the most popular diet on the planet with the most popular dieting motivation — a “holy shit, how did she do that??” before-and-after image. But it’s also just the latest iteration of the age-old allure of the transformational photo. We still don’t know whether before-and-after images are helpful or actually harmful, or even which ones you can believe. Many — even companies trying to sell weight loss in the wellness industry — are pushing back against before-and-after images as potentially harmful, saying that they create unrealistic expectations and gloss over harsh realities. How much can a picture (or two) really tell you?

Why we can’t resist a transformation

To many people, the images are motivational. On Reddit, a popular subreddit called r/progresspics has almost 650,000 subscribers; it showcases before-and-after “goal” weight loss shots but also extends to non-weight-related subjects, per the subreddit’s rules: “Progress comes in many forms other than weight loss such as addiction recovery, fitness transformations, gender changes, etc.” This subreddit is even set up so you can search people with roughly your same demographic characteristics.

There’s a psychological reason this concept is popular. “Social cognitive theories are based on people learning from observing — not just behaviors in the environment but also seeing outcomes,” Dr. Pamela Rutledge, a media psychologist, writes in an email to me. “We are more likely to internalize or adopt a behavior if we believe that the outcome is positive and achievable.” Before-and-afters give us so-called “proof” that certain outcomes are possible.

The idea that inspiration is ultimately what makes these pictures compelling resonates with the users of r/progresspics. “A progress picture inherently carries a bit of inspiration. When you’re used to telling yourself that something’s impossible, external motivation sure can help change the tide,” Clayton, a subreddit moderator who has lost more than 100 pounds, tells me in an email.

Rutledge says there are three factors that make a before-and-after so compelling. First of all, it must show a relatable conflict: someone who wants to lose 30 pounds or fix her nose after a softball injury left a bump on it. Next, it leaves a curiosity gap that keeps you hooked: How did he get that six-pack? (See: Jersey Shore’s Vinny Guadagnino, who now calls himself the “Keto Guido” and who also has a dedicated separate Instagram for his keto pursuits, with more than 700,000 followers.) Finally, it provides a satisfying resolution, a “psychological reward in seeing how something turns out.”

As such, the side-by-sides function as fantastic marketing. Plastic surgeons and dermatologists now use them liberally on Instagram, actively gaining new patients this way. The Meth Project and news outlets have used a reverse form of this to attempt to discourage meth usage, by showing how devastating its use can be on your looks.

But before-and-after photos have a long and sometimes misleading history, particularly in weight loss industry advertising. For many reasons, both WW (née Weight Watchers) and Facebook have banned the images in their ads. Companies and advertisers know how convincing they can be, but the rub is that they can be false advertising and also maybe make people feel bad about themselves.

Before-and-after photos are controversial

The weight loss before-and-after image is a time-honored tradition, and one long used by shady weight loss marketers to sell supplements and diets. The Federal Trade Commission has strict guidelines about verbiage in these types of ads. Diets frequently fail, which is why so often you’ll see in the fine print of dramatic weight loss pictures: “Results not typical.”

Facebook has also banned these pictures in advertising on its platform. Its guidelines include examples of what types of images are acceptable. For example, you can show a picture of someone’s six-pack, but not zoomed in. It notes somewhat vaguely, “Ads must not contain ‘before-and-after’ images or images that contain unexpected or unlikely results. Ad content must not imply or attempt to generate negative self-perception in order to promote diet, weight loss, or other health related products.” So, for example, it can’t show someone looking sadly at her not-flat stomach.

Then there’s WW, a company with a history of dramatically debuting the weight loss of various celebrity endorsers in big ad reveals, like Jennifer Hudson in 2010. But early in 2018, the company banned the use of before-and-after images in its ads. Gary Foster, WW’s chief scientific officer, says of the decision, “What consumers have told us over the last three years is that it really isn’t about a clear beginning and a clear end. It’s about progress.”

It’s consistent with the company’s recent pivot to (at least nominally) focus on wellness over weight loss, despite the fact that many of its users join to lose weight. Indeed, many of the most popular posts in its internal Connect social media platform are progress pictures and before-and-after shots.

“While you see a fair amount of progress pictures, our No. 1 most frequent hashtag is #NSV which stands for ‘non-scale victory,’” says Foster. This hashtag refers to achievements like being able to walk up stairs without getting breathless. “But I think the reasons consumers do it is that one picture’s worth a thousand words. It’s a very tangible way to see the degree of change that’s been made. But it’s a very surface view.”

When it comes to user-generated images, there’s no guarantee that what you’re seeing is even what that person’s body looks like. There are zillions of apps, like Facetune, that you can use to give yourself an instant transformation with nary a jog on the treadmill. (The Kardashians are constantly being accused of photoshopping images.) And in the past few years, a number of Instagram influencers have taken to the platform to show how lighting and angles can be manipulated, posting “30-second transformation” photos.

But all of this hasn’t stopped the images from being very popular with regular people, especially those trying to lose weight.

Before-and-after photos are probably not that great for our psyches in the long term

Some professionals are convinced that progress pictures and before-and-after photos are not a positive thing. Alexis Conason is a clinical psychologist in New York City who specializes in overeating disorders, body image, and psychological issues related to bariatric surgery and who offers a program called the Anti-Diet Plan.

Conason thinks these images are fundamentally flawed because they come from a “place of self-hatred” and encourage toxic dieting culture. She also notes that they only provide a snapshot of a moment in time, and that it’s impossible to know things like how much time and effort a person is putting into their appearance, whether or not they may be struggling with an eating disorder, and whether they will maintain the results long term. She also expressed concerns about unrealistic expectations put on new mothers, since many of Jameson’s “before” shots are pregnancy and postpartum pictures taken within a year after giving birth to Batel.

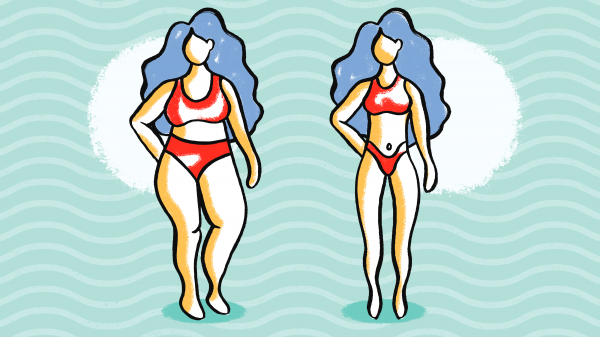

“Why we find them so compelling is that they capitalize on the fantasy that it would be so easy to transform our lives. And of course the narrative is that if we transform our body, then we’ll transform our lives: the unhappy, fat before picture and the sexy, successful, happy after picture,” Conasan says. “They promote the idea that one type of body is bad and one type of body is good.”

Erin Parks, a clinical psychologist at the University of California San Diego Eating Disorder Center for Treatment & Research (and a self-described fan of kitchen before-and-afters on Instagram), says, “There’s no data to suggest that they help motivate people to lose weight in a healthy way. When you look at change literature, we aren’t finding that images are what compel people to change.”

But proponents feel they are helpful. “There is so much more to weight loss than skinny equals good and fat equals bad,” Laura, another r/progresspics moderator, writes in an email. “I’ve seen a lot of before-and-after pictures, and almost none of them feature people who are only losing weight in order to change their appearance. Some people I’ve seen losing were doing so because they want to be able to do more with their children. Others have health issues that can be helped by losing weight.”

“Confidence” is a word that comes up again and again in this discourse; the narrative usually is that the person becomes more confident in the after picture. Michelle, another r/progresspics moderator, writes to Vox, “Many of these progress pics show women feeling more confident…You can literally see people gain self-esteem.”

It’s been questioned whether these types of pictures cause eating disorders. Before-and-after images are rampant on so-called pro-ana blogs, which openly promote disordered eating behaviors and encourage anorexia. They frequently feature such photos as inspiration. Instagram and other social media platforms have actively banned and taken down pro-ana hashtags and content.

The images can be a trigger if you are predisposed to eating disorders, but they aren’t causative. “Our research has shown that eating disorders are neurobiologically driven illnesses. So if you aren’t wired to get an eating disorder, you’re probably not going to get one,” says Parks, who notes that eating disorder etiology is complex.

“What bothers me about the pictures is that the real before-and-after that happens is not something that you can see. Often, the biggest change that’s happened is in their minds,” Parks says. She points to people with eating disorders who learn how to focus more on family and social activities and less on obsessing about their bodies, as well as people without eating disorders who start exercising and who have minimal body changes, but who gain more energy and feel stronger. (R/progresspics does feature pictures posted by people recovering from eating disorders, showing gains and openly discussing their journeys.)

So should we celebrate people’s before-and-after photos?

Ultimately, it’s difficult to assign a value to before-and-afters, because it depends on the viewer’s wiring, the type of photo it is, and the broader context.

“They can be inspirational, proof that there is good in the world,” says Rutledge, citing the examples of the scrawny dogs who become fluffy and happy again once they’re adopted.

But there are clearly times when the motivation can turn to self-hatred or worse.

“If you finish looking at before-and-after pictures and you feel inspired, then good for you,” says Parks. “But what we hear from a lot of people, both who suffer from eating disorders and when we go out and talk to the general public about this chronic cultural condition of people not liking their bodies, is that they look at those pictures and they feel crappy.”

A good rule of thumb, according to Rutledge, is that images for things you can change — teeth straightening, hairstyle, painting a room — can be inspirational. Looking at things you can’t change — body build, height, the fact that you’ll never own a divine midcentury LA home like Mandy Moore — might be counterproductive.

Parks has some straightforward advice: “We would recommend not looking at things that make you feel crappy.”

Want more stories from The Goods by Vox? Sign up for our newsletter here.

Sourse: vox.com