On Tuesday, the Environmental Protection Agency and the US Army Corps of Engineers presented the Trump administration’s proposal to undo a major Obama-era environmental regulation, the Clean Water Rule.

The rule defined the “Waters of the United States,” a.k.a. WOTUS. These are the rivers, streams, and lakes that fall under federal jurisdiction and forms the foundation of a massive piece of environmental regulation, the Clean Water Act.

The Obama rule, first published in 2015, was meant to clarify which streams and wetlands fall under federal clean water protections — a question that had been causing legal frustration for years.

But it triggered fierce blowback from farm and industry groups across the country. “Opponents condemn it as a massive power grab by Washington,” Politico reported, “saying it will give bureaucrats carte blanche to swoop in and penalize landowners every time a cow walks through a ditch.” Some of those criticisms were overblown (it doesn’t cover puddles, for instance), but the rule was widely cited by conservatives as a perfect example of EPA overreach under President Obama.

Last year, President Trump signed an executive order directing the EPA to begin the long process of repealing the Clean Water Rule and replacing it with … something else.

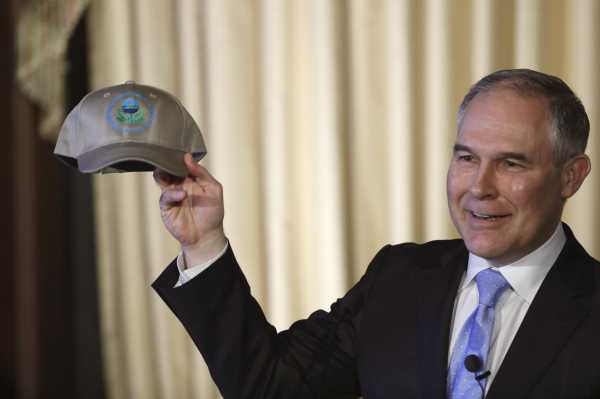

Earlier this year, the EPA suspended the Obama rule. And on Tuesday, the agency revealed its replacement, one it said will smooth over the problems that made the 2015 regulation so contentious.

“For the first time, we are clearly defining the difference between federally protected waterways and state protected waterways,” said EPA acting Administrator Andrew Wheeler in a press release. “Our simpler and clearer definition would help landowners understand whether a project on their property will require a federal permit or not, without spending thousands of dollars on engineering and legal professionals.”

However, environmental groups said the new definition would cut the number of waterways the federal government must regulate, leaving them vulnerable to pollution. It excludes, for example, waterways that flow only for parts of the year, like after rainstorms while snow melts.

“This sickening gift to polluters will result in more dangerous toxic pollution dumped into waterways across a vast stretch of America,” said Brett Hartl, government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity, in a statement. “The Trump administration’s radical proposal would destroy millions of acres of wetlands, pushing imperiled species like steelhead trout closer to extinction.”

EPA officials said they didn’t know just how many waterways would be excluded from federal jurisdiction under the new proposal. However, a document obtained by E&E News showed that the EPA and the Army Corps had estimated last year that 18 percent of streams and 51 percent of wetlands would not receive federal protections under the revisions.

Tuesday’s announcement is only the beginning of a long regulatory and legal process. The EPA is taking comments on the proposal for 60 days and will host a listening session in Kansas City, Kansas, in January. In the meantime, it’s worth understanding how WOTUS became so controversial and what it means for huge swaths of the country. Here’s what you need to know.

What the Waters of the US rule actually does

To understand this rule, we need to go back to 1972, when Congress passed the Clean Water Act. That law features dozens of regulations and permitting requirements for anyone discharging pollution into the “waters of the United States” in a way that could affect human health or aquatic life. These rules apply to factories, power plants, golf courses, new housing developments — and much, much more.

For example, under the law, a facility storing oil that could leak needs to prepare a spill prevention plan aimed at minimizing discharges. If the facility is far away from any “waters of the United States,” however, it doesn’t face these requirements.

But here’s the tricky part. The Clean Water Act doesn’t precisely define what “waters of the United States” means. That’s left to the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers. And it’s a hard question. For instance, the law is clear that major navigable rivers and lakes and any connected waterways should be protected. That includes major rivers like the Mississippi River, the Colorado River, and the Ohio River. But what about waterways that are only loosely connected? What about the 60 percent of streams that are dry for part of the year but then connect when it rains? Any pollution dumped into those waters could affect key ecosystems. Should they be regulated?

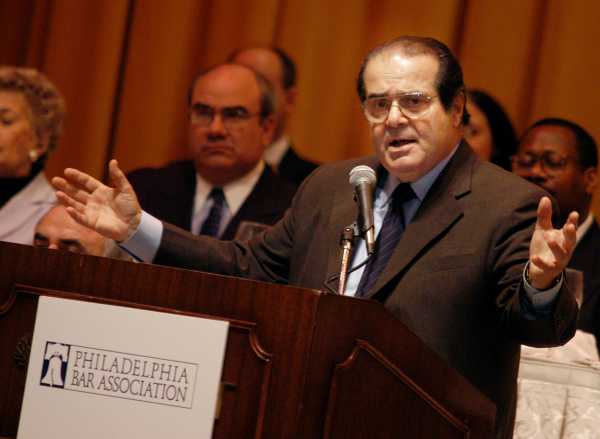

In the 2000s, this uncertainty led to a pair of Supreme Court decisions that only ended up creating more bewilderment. In a split decision in Rapanos v. United States in 2006, Justice Anthony Kennedy argued that Clean Water Act protections applied to wetlands that “significantly affect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of other covered waters.” But Justice Antonin Scalia argued that protections only applied to wetlands “with a continuous surface connection” to navigable water — a far smaller number of wetlands. And it wasn’t totally clear which opinion took precedence.

“The short answer is that the state of post-Rapanos wetlands jurisdiction is a mess,” Richard Frank of the University of California Davis told Greenwire in 2011. In the ensuing years, whenever a dispute arose over whether a landowner — be it a housing developer, a golf course, a farm, or what have you — needed a Clean Water Act permit or not, courts had to resolve it on a case-by-case basis.

So under Obama, the EPA and Army Corps of Engineers tried to bring clarity to the matter. They sifted through more than 1,200 scientific papers to figure out which types of bodies of water were important to aquatic ecosystems and therefore deserved protection, per Kennedy’s opinion.

The final Waters of the US rule, published in June 2015, outlined which bodies of water were automatically covered by the Clean Water Act — requiring permits for discharges or dredging or dirt fill — and which ones still needed to be dealt with on a case-by-case basis. For instance:

- In the past, tributaries of navigable rivers were evaluated on a case-by-case basis. But under the new rule, they’re automatically protected if they have a bed, a bank, and a high-water mark. This includes many streams that are dry for part of the year. Waterways without these features are still dealt with case by case.

- Wetlands and ponds are now automatically covered if they’re within 100 feet or within the 100-year floodplain of a protected waterway. Otherwise, it’s case by case.

- Certain “isolated” waters that are not connected to navigable waters now get automatic protection if they have a “significant nexus” to protected waters — like the vernal pools of California.

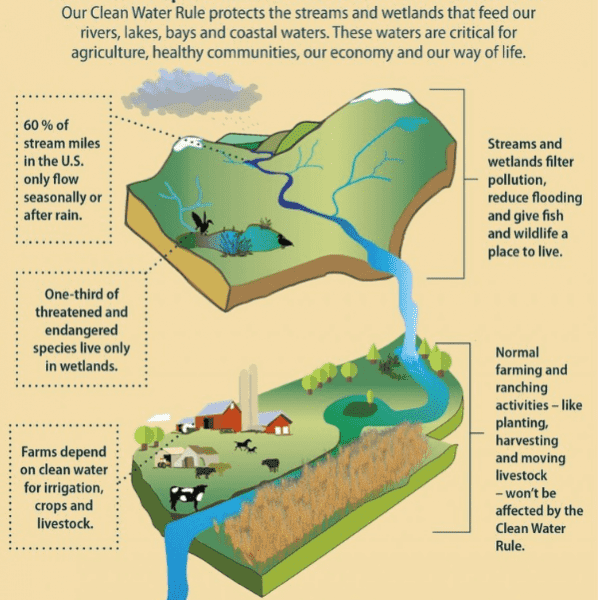

The rule also explicitly exempted a number of bodies of water often found on farms, such as puddles, ditches, artificial ponds for livestock watering, and irrigation systems that would revert to dry land if irrigation were to stop. Here’s a graphic:

For its part, the EPA argued that this rule didn’t significantly expand the waters under its jurisdiction. Rather, it created more certainty for about 3 percent of the nation’s waterways — to avoid bringing cases to court every time there was a legal gray area. According to the EPA, the rule offered clearer protection to upstream bodies of water that contribute to drinking supplies for one-third of the population.

Before the rule came out, few who worked on it expected widespread blowback. “This rule will provide the clarity and certainty businesses and industry need about which waters are protected by the Clean Water Act,” Obama said when the final rule was announced. But things turned out very differently.

Why the Waters of the US rule became so controversial

Opponents of the rule — particularly farming and ranching groups — clearly didn’t buy the EPA’s line that this was only a technical update. Nor were they comforted by the EPA’s exemptions for agriculture. Instead, they called it a power grab.

“The agency is making it impossible for farmers and ranchers to look at their land and know what can be regulated,” argues the American Farm Bureau Federation on its site. “EPA has vastly expanded its authority beyond the limits approved by Congress and affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court.”

Some Western farmers, for instance, fretted about the open, unlined canals they use to irrigate their lands during the growing season. These systems divert water from streams, serve as water sources for wildlife, and can connect to larger bodies of water elsewhere. As Reagan Waskom and David Cooper of Colorado State University explain, farmers and ranchers feared that these canals would fall under the rule’s definition of “tributary” and might have to be replaced by costly pressurized pipes. Or, alternatively, that fertilizer use near these waterways would be more strictly regulated.

Defenders of the rule dismissed these scenarios. Jon Devine, a lawyer with the Natural Resources Defense Council, pointed out that the Clean Water Act has always regulated agriculture lightly. “This rule doesn’t really change those exemptions,” he says. Indeed, one recent study found that the EPA’s jurisdiction over farms actually shrank under the new rule.

The EPA was also pretty explicit that it wouldn’t target farmers. “We will protect clean water without getting in the way of farming and ranching,” then-EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy told the National Farmers Union in 2015. But few farmers or ranchers believed her. Their argument was that the rule was vague enough that the EPA could crack down on them if it chose. It’s basically a question of trust. And at the moment, conservatives are not particularly inclined to trust the EPA.

Joni Ernst, a Republican senator from Iowa, made that clear in former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt’s confirmation hearing in 2017. “My constituents tell me the EPA is out to get them rather than work with them and there is a huge lack of trust between many of my constituents and the EPA,” she said. “If we take a look specifically at the WOTUS rule, Iowans truly feel that the EPA ignored their comments and concerns, threw them under the rug and then just moved forward.”

However the backlash started, it took on a life of its own. Trump began citing the water rule on the campaign trail as an example of EPA overreach, earning cheers from rural audiences. In signing his executive order in March, he called it a “destructive and horrible rule.”

Why it will be difficult — but not impossible — for the EPA to undo the Obama-era WOTUS rule completely

Pruitt delayed the Obama WOTUS rule’s implementation for two years, buying the EPA time to come up with an alternative.

But implementing a new definition for WOTUS requires proposing a new rule that’s supported by extensive scientific and legal arguments, opening up the proposal for public comments, responding to those comments, and then defending the final rule in court as a superior approach. This could take years.

And much of the ambiguity around which waterways deserve Clean Water Act protection still holds even if you repeal the Obama rule. Which wetlands are covered? How do you deal with streams that flow part of the year? How do you interpret that mess of a Supreme Court decision in 2006?

In his executive order, Trump asked the EPA to consider Scalia’s opinion in Rapanos, which extended protection to wetlands only if they had a “continuous surface connection” to navigable waterways and extended protection to streams only if they were “relatively permanent.” So it’s not surprising that acting EPA Administrator Wheeler’s replacement rule would cover far fewer waterways — leaving out, for instance, many of the 60 percent of streams that don’t flow year-round.

Environmental groups say that’s a problem. Devine argues that polluters could take advantage of a weaker rule with less certain protection for streams and waterways. As long as there’s ambiguity about where the Clean Water Act applies, it would be harder for citizen groups or the Department of Justice to bring a case against companies dumping chemicals or other pollutants into smaller bodies of water upstream.

“Without this rule, enforcement has been unpredictable,” Devine says. “The EPA has mainly been focused on big rivers and lakes so that they wouldn’t have to litigate to the ends of the earth about whether the Clean Water Act applied to waters upstream. But if you can only regulate the biggest rivers and lakes — and the pollution problem is much farther upstream — then you’re not effectively protecting the receiving water or the watershed.”

Still, it’s not clear that the EPA can scale back the water rule significantly. Federal courts have typically embraced Kennedy’s more expansive interpretation of the Clean Water Act rather than Scalia’s, and any rollback of Obama’s rule would still leave plenty of legal gray areas where the courts will need to decide on a case-by-case basis whether the Clean Water Act applies. “It’s going to be incredibly complex to figure this out,” says Richard Revesz, a professor of environmental law at New York University.

Further reading:

- Repealing the clean water rule is only step one for Trump. He’s also targeting Obama’s signature climate policy, the Clean Power Plan. Read here for more on how he might do that.

- The EPA is also rolling back restrictions on major sources of toxic air pollution.

Sourse: vox.com