Period-tracking apps are not for women

The golden age of menstrual surveillance is great for men, marketers, and medical companies.

By

Kaitlyn Tiffany@kait_tiffany

Nov 13, 2018, 8:30am EST

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

Period-tracking apps are not for women

tweet

share

A cartoon cloud told me I might be pregnant.

Its little cloud body drifted across my iPhone screen: “7 days late!” written in friendly blue lettering on its belly. It was very cute, and indeed, two pregnancy tests later, it could be confirmed that I was pregnant — not cute at all. “8 days late! 9 days late! 10 days late! 11 days late!” the cloud informed me, as the day of my abortion approached. “25 days late! 36 days late! 41 days late!” it announced, as I waited six weeks for my post-procedure cycle to reset. When it did, I realized I couldn’t just go back to logging my period as normal: The app would think I’d undergone a cycle more than twice as long as usual and adjust all my averages, rendering all of its future predictions completely useless to me.

I had been using the same ad-riddled, ultra-pink app since I bought my first smartphone in 2014, and now I was going to have to delete all of its learnings and start over. There was no way to explain to it that something out-of-the-ordinary had happened to my body, and while this wasn’t a huge inconvenience, it did strike me as wildly silly. I mean, the culture I live in had already done a thorough enough job prompting me to codify myself as a “bad” woman, and now some poorly designed app was telling me I was also bad data.

In the past three years, an estimated $1 billion of investment has been poured into women’s health technology. This has nothing to do with the tech industry becoming pro-woman.

The “femtech” market is estimated to be worth $50 billion by 2025, but globally, only 10 percent of investor money goes to women-led startups. At Apple, women hold 29 percent of leadership positions and 23 percent of tech positions, and almost all of those women are white. This is very much the industry standard — if anything, slightly better than it. Because “femtech” is everywhere these days, it’s easy to forget that when Apple Health debuted in 2014, senior VP of software engineering Craig Federighi told users, “You can monitor all of your metrics that you’re most interested in.” This did not, for nearly a year, include period tracking.

In Apple Health today, users can log not only their menstrual cycles but their basal body temperature, their cervical mucus quality, and results from their ovulation tests. The resulting graphs and data displays are academic-looking and confusing, and most of this data must be collected elsewhere first (there’s no iThermometer or MacMucus, you know, yet).

To fill in the gaps, there’s a handful of fancy, venture-funded period-tracking apps. And there are hundreds of free, ad-supported, easy-to-use apps that track menstruation and fertility and simultaneously invite users to track their diet, their workouts, their sex lives, their mood, the state of their skin, the smell of their vaginal discharge. They are mostly glitchy and cheaply made, and the result of opportunists seeing a need and kind of, not really, fulfilling it.

In the health category, this type of app is reportedly the fourth most popular among adults and second most popular among adolescent women. My floating cloud app was one of these junky, generic options, and the choice to download it was not an educated one; it was just whatever the App Store guessed I would want when I typed in “period tracking” more than four years ago.

This app wasn’t designed for me. It wasn’t designed for anyone who wants to track their period or general reproductive health. The same is true of almost every menstruation-tracking app: They’re designed for marketers, for men, for hypothetical unborn children, and perhaps weirdest of all, a kind of voluntary surveillance stance.

Sara Wachter-Boettcher, author of Technically Wrong: Sexist Apps, Biased Algorithms, and Other Threats of Toxic Tech, tells me that “you still see underinvestment and underdevelopment of those features that are used most often by women.”

“Yeah, sure, [Apple] added period tracking, but you see some holdover effects of that,” she says. “You still have to use a lot of third-party apps to track women’s health.”

There have been free period-tracking apps ever since there have been apps, but they didn’t really boom until the rise of Glow — founded by PayPal’s Max Levchin and four other men — in 2013, which raised $23 million in venture funding in its first year, and made it clear that the menstrual cycle was a big business opportunity.

By 2016, there were so many choices, surrounded by so little coherent information and virtually zero regulation, that researchers at Columbia University Medical Center buckled down to investigate the entire field. Looking at 108 free apps, they concluded, “Most free smartphone menstrual cycle tracking apps for patient use are inaccurate. Few cite medical literature or health professional involvement.” They also clarified that “most” meant 95 percent.

The Berlin-based, anti-fluff app Clue, founded by Ida Tin, would seem like an answer to this concern. It’s science-backed and science-obsessed, and offers a robust, doctor-sourced blog on women’s health topics. It arrived the same year as Glow but took several more to raise serious funding, provided mostly by Nokia in 2016. Today, Glow has around 15 million users and Clue has 10 million. There are still dozens of other options, but they’re undeniably the big two.

Still, they are not built for women.

“The design of these tools often doesn’t acknowledge the full range of women’s needs. There are strong assumptions built into their design that can marginalize a lot of women’s sexual health experiences,” Karen Levy, an assistant professor of information science at Cornell University, tells me in an email, after explaining that her period tracker couldn’t understand her pregnancy, “a several-hundred-day menstrual cycle.”

Levy coined the term “intimate surveillance” in an expansive paper on the topic in the Iowa Law Review in 2015. At the time, when she described intimate data collection as having passed from the state’s public health authorities to every citizen with a smartphone, she was mostly alone in her level of alarm. This was just after Apple Health launched (sans menstrual tracking), hailed as the future of medical care. But even before that, Levy argued, the “data-fication” of romantic and sexual behaviors was everywhere. There were smart pelvic floor exercisers that could pair with smartphones via Bluetooth. There were sex-tracking apps that quantified performance by counting thrusts and duration and “noise.”

“The act of measurement is not neutral,” Levy wrote. “Every technology of measurement and classification legitimates certain forms of knowledge and experience, while rendering others invisible.” Sex tracking apps and their ilk “simplify highly personal and subjective experiences to commensurable data points.”

“Every technology of measurement and classification legitimates certain forms of knowledge and experience, while rendering others invisible”

Levy also pointed out that popular period-tracking app Glow, in addition to tracking menstruation and cervical mucus quality and other typical hallmarks of fertility monitoring, asked female users to log each time they had sex, including what position they were in during ejaculation. Glow Nurture, the iteration of Glow designed for pregnant women to track their symptoms, exercise, diet, prenatal vitamins, and so on, also asked women to track their moods and provided a “mirror” app for the woman’s partner, which would ask them to provide an “objective” reading of that mood.

At the time of Levy’s writing, she described an app called iAmAMan, which allowed men to track multiple girlfriends’ periods at the same time, setting up alerts for when they could expect PMS or “horniness” or too much blood. (“Each girl can be set with their own separate password, so when you punch it in, it looks like you’re only tracking her,” the app’s description read.) That app has since been removed from the app store, but others have taken its place. I had no problem downloading and using one called PeriodMe, which will send me notifications when my roommates are about to start PMSing.

Obviously, those are niche products that aren’t being created by major companies or signing up sizable user bases. But they reflect a mode of thinking that’s common in the category. In 2015, Glow would remind women who were trying to become pregnant and entering a fertile window to wear nice underwear that day, and it would also remind their partners to bring home some flowers.

Maggie Delano, a quantified self scholar and PhD candidate at MIT, had an experience similar to mine. She wrote about period-tracking apps in a popular Medium post in 2015. Delano couldn’t get Clue to understand that she had a shorter, often irregular cycle because it literally wouldn’t let her input a cycle that short, and it wouldn’t let her remove the algorithmically generated “fertile window” from her calendar despite the fact that there was no physical possibility of her getting pregnant with her partner, who was also a woman.

“These assumptions aren’t just a matter of having a few extra annoying boxes on the in-app calendar that one can easily ignore,” she wrote. “They are yet another example of technology telling queer, unpartnered, infertile, and/or women uninterested in procreating that they aren’t even women.”

Glow was even worse. The first onboarding screen asks users to choose their “journey” and provides three choices: avoiding pregnancy, trying to conceive, and fertility treatments. “Five seconds in, I’m already trying to ignore the app’s assumptions that pregnancy is why I want to track my period,” Delano wrote.

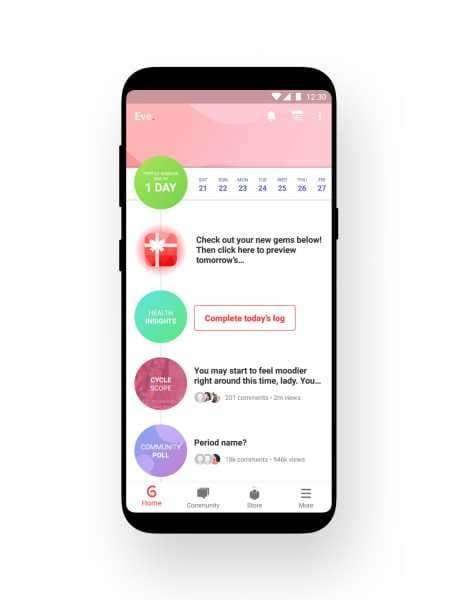

Glow launched with the promise of using data to “help you get pregnant.” In 2014, it raked in a funding round of $17 million — including major investments from Andreessen Horowitz and the Founders Fund — which it then used to branch out from its initial pregnancy-oriented offerings and create Eve, an app for documenting “your period and sex life.” This was a logical decision: Glow realized half of its users were not trying to get pregnant but trying to avoid getting pregnant. And those are very different market demographics.

“People are realizing, oh, women or cycling people spend money on things and we want money from them,” Delano tells me in a phone call. “But the assumptions drive the products in a weird direction.”

The first iteration of Eve was criticized for referring to its users as “girls” and describing sex with cutesy emoji code that centered solely on dicks: banana with a condom, banana without a condom, or no banana. In the current iteration of Eve, the emoji code is banana with a condom, banana without a condom, or a peach, and users can still redeem collectible gems to get sex tips.

The app still opens with a landing screen that says “Get it, girl.”

Period-tracking apps are not conceived of as mass-market products but as niche products: “shrink it and pink it,” the familiar guiding ethos of sportswear and basic household tools. They have odd design elements, like floating clouds, superfluous flowers, and strange faux-empowering language where straightforward medical terminology would more than suffice. They’re a product of the culture of Silicon Valley user interface design: mostly male, and predicated on quantitative metrics like interaction counts and time spent.

“Popular wisdom about ‘engagement’ meets weird ideas about femininity, and you get a lot of design and product choices that are quite questionable,” Wachter-Boettcher tells me. “It’s funny because people don’t do this kind of thing if they’re designing a health app about literally anything else.”

Can you imagine a glucose-tracking app laid out in Candy Crush aesthetics? How about a blood alcohol content tracker shouting out its users as “bro” each time they opened the app? Of course not! But you’re just tracking your period symptoms for fun, or to avoid being caught on a long car ride without a tampon, right? Why not decorate it?

The ways in which period-tracking or fertility-tracking apps are different reveal the ways most designers think of them: as products that provide information that’s not actually very serious or important medically, and that should exist mostly to convince a woman to spend as much time as possible looking at ads, while supplying the owner with as robust a data set as possible, so they can better target more ads.

“It’s good enough” is the refrain Wachter-Boettcher says she hears from women. “It does what I need, but I don’t know why it’s making this assumption or that assumption.”

The University of Canberra’s Deborah Lupton — a researcher focused on what she terms “quantified sex” — told the Atlantic in 2014 that the way period-tracking and fertility-tracking apps are lumped together shows you everything you need to know about how developers think of women. “When you look at these types of apps, they’re completely about the surveillance of pregnant women,” she said, “making them ever more responsible and vigilant about their bodies for the sake of their fetus.”

The data they generate can also be shared with developers, advertisers, researchers, and data brokers. Patient Privacy Rights founder Deborah Peel told the Washington Post in 2016 that reproductive health data is uniquely valuable to marketers — knowing that someone is preparing to become a parent means knowing that someone is about to enter one of the very few life stages in which they’re likely to get “hooked on new brands.”

The commercialization of pregnancy is not exactly a new concept, but it’s reached a fever pitch in the digital age, when marketing to someone based on the hormones and genetic material swimming in their abdomen is as simple as pulling a few key pieces of easily trackable data.

“When you look at these types of apps, they’re completely about the surveillance of pregnant women”

In some cases, this data is not even in anonymized formats. In 2016, Consumer Reports found security vulnerabilities in Glow so severe that user profiles could be accessed by “someone with no hacking skills at all.” That might sound like an exaggeration, so let me put it to you another way: The way Glow was set up in 2016, all you had to know in order to see a user’s full profile and account information was their email address, which is what led reporter Kelly Weill to dub the app “a jackpot for stalkers.” (Glow quickly fixed the issue and commented, “There is no evidence to suggest that any Glow data has been compromised.”)

Today, the app has 15 million users, and this type of scale is its own pressure: Glow is now the only HIPAA-certified reproductive health app, and its 2016 panic was followed by a third-party security audit. That’s great! Unfortunately, scale is also what allows a tech company of this size — and with this obligation to investors — to open a whole other can of worms. With a wealth of fertility data at its disposal, Glow has expanded into the trendy business of IVF and egg freezing, equipped with a marketing strategy I don’t really think we should even try to get into without some light sedation, but we have no choice.

In a questionnaire on the app’s website, Glow promises to debunk common myths about egg freezing (a procedure that can be invasive and cost tens of thousands of dollars, and which has not been done frequently enough to have reliably citable success rates), insisting that even though your gynecologist will tell you that you don’t need to worry about it in your 20s, you really ought to consider it.

Glow’s approach is even seedier than a swanky informational IVF cocktail party, in that it preys on women who have been logging years of intimate data. You haven’t gotten pregnant yet? Well, we’re not necessarily saying it should concern you, but if anyone would know, wouldn’t it be us?

If the goal of tech-enabled health tracking is to empower users to make informed medical choices, Glow is a great example of how not to do that. It takes its millions of users on a well-designed, user-friendly, fertility-obsessed road that ends in promises that egg freezing is a logical thing to pursue in your mid-20s. CEO and co-founded Mike Huang has also said that Glow data may be used to make “more accurate risk assessments … which will ultimately result in better health insurance,” an interesting comment given that the major North American life insurance company John Hancock announced last month that it will only sell “interactive” policies that track health via smartphones and wearables.

Clue gives anonymized data to scientific researchers, encrypts its identifying information separately, and discloses all of its research projects in detail on its website. Tin tells me, “Our scientific collaborations are exploring questions like what pain patterns are considered ‘normal’ in which populations? What mood patterns do we see around ovulation? How might our menstrual and symptom patterns help us spot disease and illness earlier?”

More recently, after our call, Tin made headlines by disclosing that Clue saw a huge spike in users reporting “sadness” in the daily mood-tracking section of the app in the wake of the 2016 election. Cool?

“People, they share data about the most intimate parts of their lives. They talk about their mood, they talk about their pain, they talk about their sex lives. If you ask people to share this data, you’ve got to have ethical conversations about what you’re going to do with that data,” she said in the same talk.

Tin tells me that Clue’s pill-tracking feature — in tandem with regular logging of pain, mood changes, and bleeding — has helped users figure out that they need to switch to a different pill. And with all its trackable categories, Clue “helps [users] identify correlations between their cycles and general well-being, such as an increase in stress levels or a decrease in their sex drive at certain points in their cycle.”

It’s all fine, good even. I guess I don’t care if she talks about mood trends in public, if her product is going to help people figure things out about their bodies. At the same time, it is deeply weird and makes me feel alienated from my own body, to tattle on it in such a precise, point-by-point way. I downloaded Clue last month, and each time I inform it that I have taken my birth control pill, or that I’ve had sex that day, or that I experienced spotting or a mood swing, a tiny animation responds and tells me “Clue is getting smarter!”

I don’t want to tattle on my body in such a precise, point-by-point way

Gross? I’m trying to be thorough because that seems like I what I am being told I ought to do if I care about my health, or the algorithm, or research about women’s health. Would my boyfriend think it’s freaky that I’m keeping a log of the particulars of our sex life? I mean, I certainly wouldn’t show it to him. It’s all fine; it’s all so undignified.

And while period-tracking apps broadly come with minor annoyances and sinister fine print, we haven’t even talked about the ways that lazy research and bad design can tangibly ruin lives. This summer, amid the dozens of headlines about the Apple Watch’s Food and Drug Administration–approved EKG feature, there was a lighter buzz around a tech company called Natural Cycles. The FDA announced in August that its app’s algorithm was so good at predicting fertility windows, it could officially market itself as contraception.

Except it was only 93 percent accurate — only working for women who cycled “regularly,” which excludes a lot of people — and Facebook ultimately pulled its ads for being misleading. One Swedish hospital alone reported 37 unwanted pregnancies last year in women who were using Natural Cycles as contraception, out of a total of 668 women who sought abortions at the hospital all year.

In July, novelist Olivia Sudjic wrote for The Guardian about her experience seeking an abortion after using Natural Cycles, saying, “I felt colossally naive. I’d used the app in the way I do most of the technology in my life: not quite knowing how it works, but taking for granted that it does. Speaking to others who bought the app as contraception (about 75 percent of Natural Cycles’ total user base, according to its CEO), it seems that many felt the same.”

Natural Cycles was marketed to women primarily on Instagram, by dozens of pretty, 20-something influencers who vouched for it as foolproof. The demographic the ads are shown to — and 50 percent of its subscriber growth came from these ads — is susceptible to the ads because of their youth and because of their anxiety about getting pregnant.

Anxiety is profitable. Fear is profitable. Desire is profitable. If you desire pregnancy or fear pregnancy, someone can make money off you. If you don’t, well, don’t bother tracking your health. It isn’t worth anything.

Want more stories from The Goods by Vox? Sign up for our newsletter here.

Sourse: vox.com