For Democrats, there should be one big fear heading into the 2020 election: A booming economy could save Donald Trump.

The adage “it’s the economy, stupid” has condensed the conventional wisdom to four words: Voters (rightly or wrongly) hold the president accountable for America’s financial health, and their perceptions of how they and the country are doing economically will be the most important factor when they vote. Politico was already reporting last year, using economy-based predictors, that Trump actually seemed “on track for a landslide.”

Trump knows the relatively strong economic data is a boon for his political fortunes.

“You have no choice but to vote for me,” he told a New Hampshire crowd a few months ago, citing the health of the stock market.

But the link between the economy and presidential approval has become “increasingly untethered,” as several political scientists writing at Political Behavior put it last March. The break began during Bill Clinton’s administration and weakened considerably under George W. Bush. After Barack Obama took office, the two became completely severed:

CNN’s Harry Enten captured it this way: “Turns out for incumbent presidents, overall approval ratings are far more telling of fates.”

John Sides, the political scientist who with Lynn Vavreck wrote the seminal book The Gamble about the 2012 presidential election, told me last year, “This could complicate an election forecast.”

In other words, does the economy really tell us anything at all about whether Trump will be reelected in 2020? Who knows! We’re in uncharted territory. Nevertheless, it is worth remembering that factors beyond which Democrat prevails in the primary will be in play during the 2020 campaign against Trump.

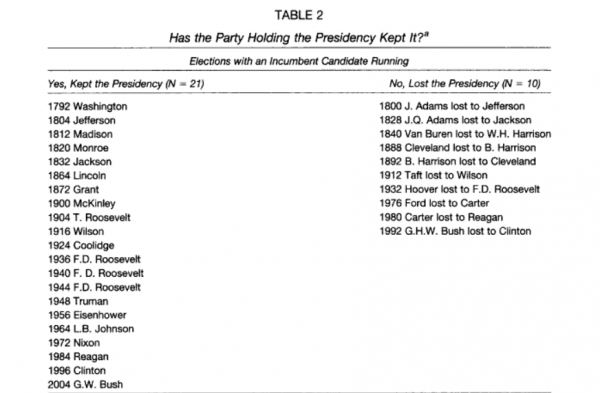

We should start here, as Vavreck emphasized to me: Trump is the incumbent, and incumbency is a proven advantage in presidential elections. Its degree and its reasons are the source of debate, but a table via David Mayhew’s research published in Political Science Quarterly in 2008 makes this obvious (and was only bolstered by Barack Obama’s win in 2012):

So Trump starts with one obvious edge heading into the 2020 campaign. Let’s consider then what we can learn — and what we can’t — from some of these other indicators about what might happen in 2020.

I’ve elected to focus on four of them: Trump’s approval rating, consumer confidence, the US gross domestic product, and the unemployment rate.

Trump’s presidential approval rating has been stubbornly low

Head-to-head polling between Trump and any prospective Democratic nominee seems nearly useless at this point. Many Americans haven’t yet formed their opinions on the various Democrats seeking their party’s nomination, and, regardless, a two-way general election tends to sharpen opinions in a way that a 12-person primary can’t.

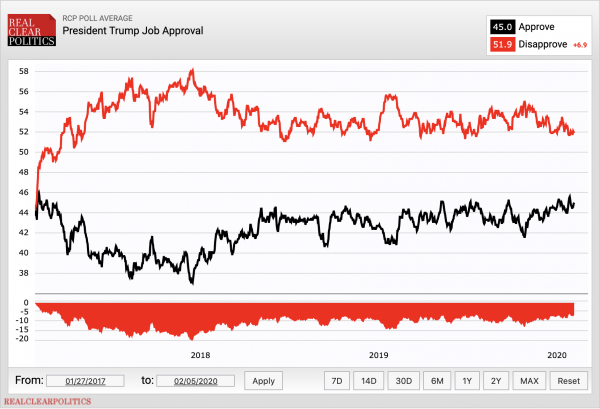

But presidential approval ratings have always been strongly linked to voting behavior, and everybody knows Trump. Here is the RealClearPolitics average of the president’s approval rating, from the start of his presidency to now:

The FiveThirtyEight polling average is a little more negative: 43.5 percent approval and 52.1 percent disapproval as of early February. Its chart follows mostly the same pattern.

Either way, Trump has been consistently unpopular throughout his first two years. At his absolute best, so far, he was 6 points more unpopular than popular. The recent uptick will have to sustain itself before we start assuming he is suddenly a more popular president.

And as Vox’s Ezra Klein wrote in 2018, Trump’s poor favorability has been in defiance of a relatively solid economy:

Trump’s approval rating is the metric to watch as we endure all the twists and turns that might precede the 2020 election. Impeachment is over. No major legislation is expected to be passed in Congress. But last month’s sudden assassination of an Iranian general is a reminder that Trump can shake up the news cycle all on his own. And then you have a billion or so other things that he can’t control but will be held accountable for responding to, like natural disasters.

A lot can happen is all I’m saying. Trump’s approval rating should capture any fluctuations in how the public feels about the man in the White House.

Consumer sentiment looks okay for Trump right now

Before we dive into the economic data, a word of warning from Sides: The debate in political science circles is whether voters care about how the economy did in the year preceding an election or if they look back over the previous two years.

Either way, when thinking about November 2020, we are either only halfway through the economic period voters will be using to evaluate the state of the country and Trump’s presidency or we’ve barely begun it and none of what’s happened so far will matter by the time people head to the polls.

“Changes in economic indicators matter more closer to the election,” Sides told me. “So the consequential economic trends, if there are any, probably haven’t happened yet.”

And things can still change: Bloomberg currently projects the chances of a recession in the next 12 months at 26 percent. That’s far from a guarantee but it’s still a decent chance. So if there is a big drop in economic conditions before the election, it hasn’t happened yet.

But we will press on, starting with consumer sentiment, a useful way to understand how the American people are feeling about the economy.

The University of Michigan provides a snapshot every month, drawing from a survey that asks US consumers if they feel better or worse off than they did a year ago, whether they expect to be better or worse off in a year, whether they expect good or bad times for the country as a whole in the next year and longer, and whether they think it’s a good or bad time to make major household purchases.

Here is how UM’s consumer sentiment index has shifted during Trump’s presidency:

This is a noisy metric, as you can see. But taking the long view, American consumers are feeling either about the same as when Trump came into office or maybe a little bit better.

That is a notable improvement on how the citizenry felt for the bulk of the Obama presidency, as pessimism persisted in the wake of the Great Recession. But it’s not quite the American renaissance Trump likes to pretend he is overseeing.

GDP growth rates show a little better news for Trump

With our final two variables, GDP growth and the unemployment rate, Sides offered one more critical piece of context: The important thing is not the absolute number, but the trend that we’ve seen since the president took office. As Sides noted, Ronald Reagan’s reelection at 7 percent unemployment might seem surprising until you recall the unemployment rate was at 10 percent when he took office.

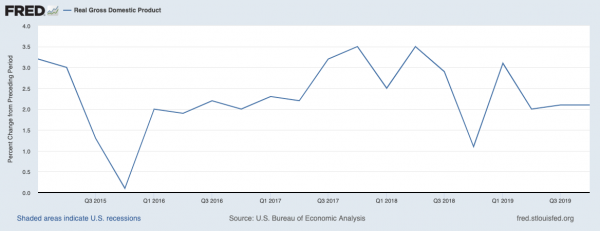

With that in mind, I decided to look at the last two years of the Obama administration and the first two years of the Trump administration. Here’s the trendline of the GDP growth rate over that time:

In general, GDP has been growing a little faster under Trump than it was at the end of Obama’s presidency. Leaving alone whether the president deserves any credit for that improvement, it would bode well for his reelection chances if it continues.

The question is whether it will. Experts consulted by the Federal Reserve expect the annual growth rate to dip below 2 percent in 2020 (it grew at a 2.5 percent pace in 2018, the last year with actual data). It’s not a guarantee, but those projections are a warning sign for the president.

The unemployment rate is still going down under Trump

Unemployment under Trump has largely maintained the trend we saw under Obama — by which I mean it’s kept going down. The jobless rate, at 3.6 percent in January, has been on a steady downward slope for the past decade, actually. But a continuation of that trend is still a good indicator for Trump.

So two more specific economic indicators look pretty good for Trump. But consumer sentiment is mixed, and the president’s approval rating is — and always has been — pretty bad.

It’s worth noting a couple of other caveats. One, these macro-trends obviously do not account for the Electoral College or the way presidential campaigns are conducted and won in the United States. How specific states are faring and feeling has an outsize impact. Second, the economic models cited by Politico include other indicators (gas prices, inflation, etc.) that we have not covered.

Regardless, the messy picture here is probably an appropriate one. Trump is unpopular and consumer confidence is middling, but the underlying economic data is quite sound.

The president is probably looking at better odds of reelection than his poor approval ratings or the unending stream of bad headlines would suggest. But he’s got weaker odds than he probably should, considering the state of the economy and his incumbency advantages.

Let us end by remembering — and I cannot emphasize this enough — we are just entering the period that will likely prove decisive in how American voters evaluate Trump at the end of his term. The 2020 election is just getting started.

Sourse: vox.com